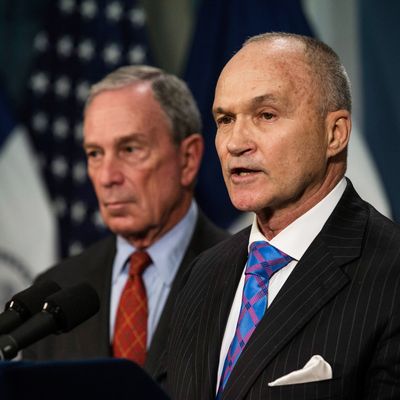

Ray Kelly has in many ways been the greatest police commissioner in the history of New York City. And now, at the start of his final two months in office, he’s being booed off the stage in Providence. That contrast is one sign that evaluating Kelly’s true legacy may take as long as the twelve years he has led the NYPD under Michael Bloomberg.

The most important parts of his record, to the life of the city and certainly to Kelly, are the big things: Crime is down drastically across the city since Kelly took office in January, 2002. That was three months after hijacked planes destroyed the World Trade Center, and there have been dozens of terrorist threats since — none of them successful. Yes, the police department didn’t do it all by itself: Community groups and demographics have helped drive down crime. The feds hunted down Osama bin Laden. But the hardest day-to-day work of protecting New York has been done, and done extremely well, by Kelly’s NYPD. Judged by the fundamental standard of the job — improving public safety — Kelly is an unparalleled success.

Ah, but the tactics, the means to that end. The past year has brought a blistering book, Enemies Within, that detailed the department’s spying on mosques. Then a federal judge declared that the way the NYPD used stop-and-frisk tactics violated constitutional rights and constituted “indirect racial profiling.” And a savvy, victorious political campaign by Bill de Blasio played to the anger of minority residents, and the queasiness of white liberals, about the overuse of stop-and-frisk.

Kelly has been complicit in both the substantive mistakes and the public-relations debacle. Trying to wring ever-better crime statistics out of precincts, he was slow to hear the complaints about the unquantifiable human cost of infiltrating Muslim neighborhoods and of stopping thousands of innocent black and Latino New Yorkers. By declining to run for mayor, which would have given Kelly the chance to make a more sustained, nuanced case for the effectiveness of his department’s crime-fighting tools, he allowed his opponents to make stop-and-frisk look like the NYPD’s only weapon. And the unflinching support of Bloomberg — which has been a boon to Kelly for most of their tenures, because the mayor has given the PC remarkably free rein — has lately boomeranged, as Bloomberg’s tone-deaf defense of the department has made Kelly look less empathetic and sophisticated than he really is.

Those qualities, underappreciated at the moment, are part of what will shape Kelly’s long-term legacy. Because while he is certainly a hard-ass, and willing to push the boundaries of civil liberties if he thinks it means greater civic order, he has also overseen an unprecedented racial and gender diversification of the NYPD. “People live in the short term,” Kelly told me once. “They take the [improved crime] situation for granted. Forty percent of the city’s population is born outside the city. We had a record crime year in 1990 — what’s been the population turnover here since 1990? Lots of new people have come in. They just accept the fact that crime is down. They don’t remember what it was like in the seventies and eighties, understandably. But we can’t forget. That’s what we’re paid to do.” Heckling Ray Kelly on his way out the door is easy. But for twelve years, and more to the city’s benefit than not, he’s been both repressive and progressive. Mayor De Blasio’s police commissioner will have a very difficult act to follow.