The initial wave of reaction to Harry Reid’s swift limited-nuclear-option strike in the Senate — shameless bipartisan hypocrisy from Republicans and Democrats who argued the opposite position eight years ago — has given way to a different sentiment: the mournful cries of the Establishmentarians. Now that the filibuster has been scaled back, what will happen to comity? Tradition? The Constitution? The dinner-party scene in Georgetown?

One recurrent version of this lament rests on the belief that the filibuster is somehow embedded in the Constitution. “This is the most important and most dangerous restructuring of Senate rules since Thomas Jefferson wrote them at the beginning of our country,” cries Senator Lamar Alexander. “I firmly believe that the filibuster is a vital protection of the minority views and exactly why the framers of our Constitution made the Senate the ‘cooling saucer,’” objects Senator Joe Manchin. In fact, the Constitution did not establish the filibuster. It set out a few, limited cases in which a super-majority vote was required, implying that the founders favored majority rule in the rest. (Indeed, that exact argument is the basis for a plausible argument that the filibuster is unconstitutional.) Thomas Jefferson and the founders explicitly opposed the super-majority principle, yet it evolved as a pure historical accident, as congressional scholar Sarah Binder has explained:

In 1805, Aaron Burr has just killed Alexander Hamilton. He comes back to the Senate and gives his farewell address. Burr basically says that you are a great body. You are conscientious and wise, you do not give in to the whims of passion. But your rules are a mess. And he goes through the rulebook pointing out duplicates and things that are unclear.

Among his suggestions was to drop the previous question motion. And they pretty much just take Burr’s advice. And once it’s gone, it takes some time for leaders to realize that they can’t cut off debate anymore. But the striking part to me was that we say the Senate developed the filibuster to protect minorities and the right to debate. That’s hogwash! It’s a mistake. Believe me, I would’ve loved to find the smoking gun where the Senate decides to create a deliberative body. But it takes years before anyone figures out that the filibuster has just been created.

You never hear filibuster devotees reverently cite Aaron Burr. I wonder why that is.

The cooling-saucer bit, while a legitimate description of the Senate’s function, has nothing to do with the filibuster, but is a description of the Senate being elected in longer, staggered increments in comparison with the House. (In any case, the House has no role in nominations at all, so easing the way for confirmation votes does not prevent the Senate from “cooling” anything emerging from the House.)

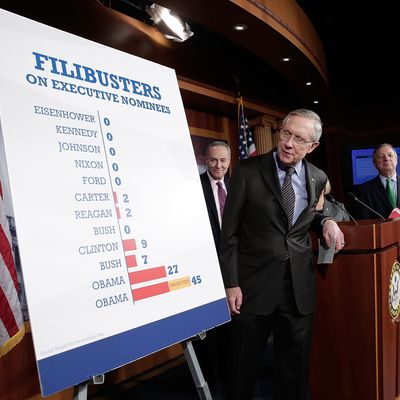

The more prevalent threat is that scaling back the filibuster will worsen bipartisan relations. The Washington Post editorial page, and two of its centrist columnists, Ruth Marcus and Dana Milbank, all excoriate Senate Democrats for what the Post calls “accelerant of poisonous partisanship.” They argue that weakening the filibuster will create more partisan rancor, undaunted by the fact that partisan polarization and use of the filibuster have risen precisely in tandem.

The bizarre, defining feature of this argument is that, unlike the crocodile tears being shed by Republicans, the centrist Establishmentarians all take the view that the Republican judicial blockade was completely unacceptable. They argue that the solution to the unacceptable blockade is that, as the Post piously insists, “Both parties should have stepped back and hammered out a bipartisan compromise reform.”

That Republicans did not offer to compromise or in any way back down from the stance the Post calls unacceptable is a fact so fatal to this argument that none of the three writers in any way acknowledges it. I would agree that a 5o-vote threshold for lifetime judicial appointments represents a sub-optimal arrangement. It would be better if there were some way for the Senate to filter out extreme nominees without having the power to wantonly blockade a vital court for nakedly partisan reasons. Given the refusal of Republicans to back down, I prefer majoritarianism to the existing alternative. The Establishmentarians refuse to grapple with the trade-off. They are against fires and fire hoses alike.

The silliest bit of hand-wringing may be the fear that allowing majority-vote confirmations for judges will pave the way for radical Republican judges. “When we have the majority,” warned Senator Charles Grassley, “when we have a Republican president, we put more people like Scalia on the court.” Except Republicans have been committed to doing this exact thing for years. Mitt Romney promised to appoint judges like Scalia to the Supreme Court. George W. Bush promised it, too. The threat to nominate more Scalias is about as frightening as Iran threatening to cut off its donations to the Jewish National Fund.

What’s more, Senate Democrats already acceded in 2005 to confirm even more conservative judges to federal courts. After Senate Republicans threatened the nuclear option, Democrats agreed to stop filibustering except in the case of “extraordinary circumstances.” How extraordinary? Well, they confirmed Janice Rogers Brown, who, among other wild statements, called the post–New Deal state “the triumph of our socialist revolution.” Republicans have already maxed out on how extreme a candidate they could find who was still able to graduate from an accredited law school and pass the bar exam. There is nothing left to threaten here.

The much smarter argument, laid out by Jonathan Bernstein, posits that deal-making Republicans wanted the nuclear option. Why? Because the deal the Senate had reached earlier in the summer – the sort of deal the centrists pine for – put them in an impossible position. They essentially called for Republicans to stop filibustering Obama’s appointments unless they had a genuine objection to the nominee in particular, as opposed to a general desire to block any nominee at all. That agreement required a handful of pragmatic Republican Senators to trade off voting to break Republican filibusters. The rise of the Ted Cruz wing made such votes increasingly painful and impossible for them to take.

That argument, if correct, would imply that the nuclear-option deal makes bipartisanship more possible, not less, by freeing up deal-making Republicans from having to constantly antagonize conservative activists. Now, this doesn’t mean that bipartisan comity is assured from here on out. Partisan polarization is a sweeping historical force in American political life, for good or ill, and nostalgic historical fantasies are less a cure for this than a refusal to live in the real world.