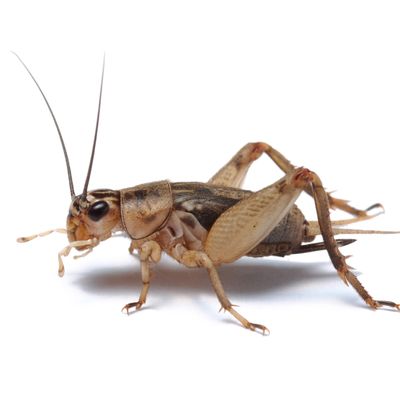

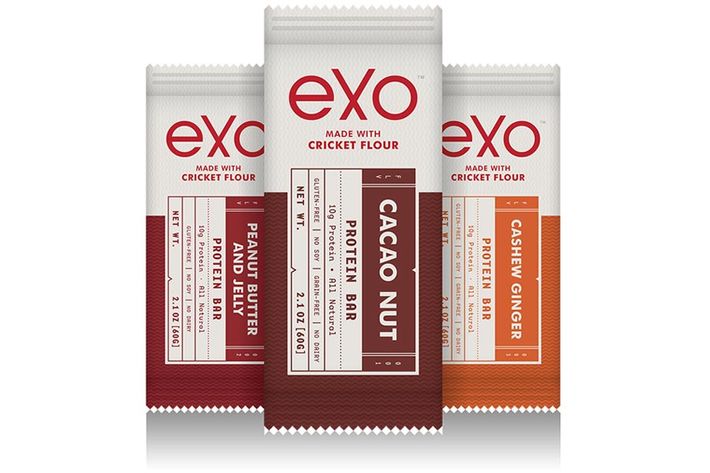

Gabi Lewis and Greg Sewitz needed a creative solution: People aren’t exactly lining up to eat bugs, and bugs were what they were selling. Their company, Exo, had gotten a lot of buzz, but they were eager to get their protein bars — featuring live-frozen, oven-dried, ground crickets (yes, crickets, but organically fed ones) — beyond their current customer base of Paleo-diet devotees and really, really stoned college kids.

As the two recent Brown graduates met with prospective clients and funders, they stumbled onto a potential answer to their marketing woes: kosher certification. “When we went into it, we assumed that kosher food was very niche,” said Lewis. “But people from all walks of life were curious whether crickets in general, and our bars specifically, were kosher. We realized that even if you don’t eat kosher, people value it as a marker of general quality.” In short, the commercial value of a kosher certification might be about a lot more than a sales spike at Passover.

They started wondering whether it would be possible to get the bars certified. More and more, they came to believe that a religious affiliation would help the hesitant consumer overcome concerns about both ethics and grossness alike.

A little investigation yielded what seemed to be a slam dunk: According to the Old Testament, there are specific species of chagavim — four-legged, winged insects, including certain types of crickets — that are in fact kosher. Bolstered by this discovery, Lewis reached out to koshering agencies like the Orthodox Union and Earth Kosher. But his requests for certification were summarily dismissed. (As one rabbi put it: “While it’s an interesting conversation, I’m too busy to have it.”)

The issue, according to Rabbi Daniel Smokler of NYU’s Bronfman Center for Jewish Student Life, is that Ashkenazi Jews haven’t eaten insects in a couple thousand years (and it’s not clear that they ever did), so they’ve lost the knowledge of which species are and are not treif. Though small groups of Jews, among them Yemenites, do still have a tradition of eating kosher bugs, the process of finding an observant, insect-eating community with Jewish legal authority and putting a system into place to certify the operation would be, as Rabbi Smokler put it, “a whole headache.”

Rabbi Zushe Yosef Blech, the author of Kosher Food Production and the kashrus administrator at Earth Kosher, was more blunt: “It just ain’t gonna happen.”

But Lewis and Sewitz, both of whom are Jewish but were raised in non-kosher households, aren’t giving up. “Gabi and I freely admit we’re not experts in Jewish law,” said Sewitz. “But we think they’re kosher.” They’ve taken comfort from the fact that there are a few ecologically minded rabbis who think Jews should lead the way in encouraging the world to embrace the consumption of insects, which, as protein sources go, are about as environmentally efficient and nutritious as it gets.

Rabbi Smokler acknowledges that there is, at least theoretically, an argument to be made in Exo’s favor. “Because Jewish law is a dynamic, active process,” he explained, “we can lose or gain traditions.” He cited the example of how quinoa, a New World crop that Jews didn’t know in biblical times, was recently certified as kosher for Passover. (Ashkenazi Jews don’t eat grains during Passover, but quinoa is actually a seed.) In response to pressure from observant Jews who wanted to be able to serve quinoa sushi and pilafs during those eight matzo-and-potato-filled days, kosher certification agency Star-K sent a mashgiach, or koshering supervisor, down to Bolivia to certify quinoa as kosher.

“It’s probably only a matter of time before someone does that with chagavim,” Rabbi Smokler said, adding that he understood the Exo founders’ persistence. “If I were trying to market insects to people, I would muster any authority that I had.”