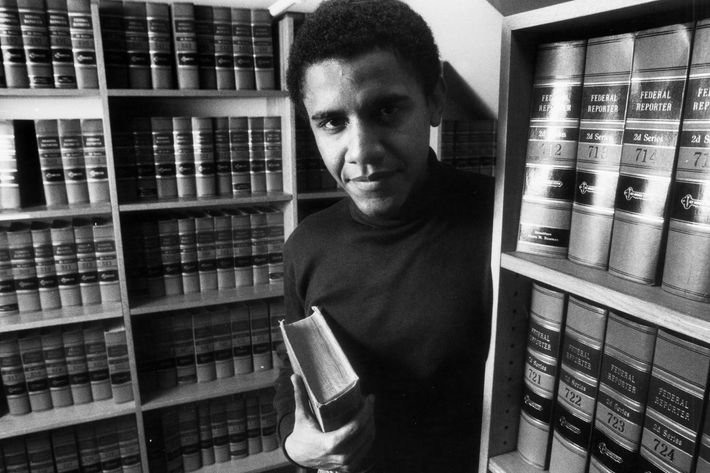

Three months ago, President Obama gave an interview to David Remnick, who asked him about the role race has played in public opinion during his presidency. When I read Obama’s reply, I winced:

>“There’s no doubt that there’s some folks who just really dislike me because they don’t like the idea of a black President,” Obama said. “Now, the flip side of it is there are some black folks and maybe some white folks who really like me and give me the benefit of the doubt precisely because I’m a black President.”

“There is a historic connection between some of the arguments that we have politically and the history of race in our country, and sometimes it’s hard to disentangle those issues,” he went on. “You can be somebody who, for very legitimate reasons, worries about the power of the federal government — that it’s distant, that it’s bureaucratic, that it’s not accountable — and as a consequence you think that more power should reside in the hands of state governments. But what’s also true, obviously, is that philosophy is wrapped up in the history of states’ rights in the context of the civil-rights movement and the Civil War and Calhoun. There’s a pretty long history there. And so I think it’s important for progressives not to dismiss out of hand arguments against my Presidency or the Democratic Party or Bill Clinton or anybody just because there’s some overlap between those criticisms and the criticisms that traditionally were directed against those who were trying to bring about greater equality for African-Americans. The flip side is I think it’s important for conservatives to recognize and answer some of the problems that are posed by that history …”

Why did I wince? Because at the time, I was deep into work on what became this week’s cover story, and here was Obama, in a highly prominent forum, stating what was already my thesis. As a journalist, you never want anybody to claim your idea first, especially if that person is also the most famous person in the world.

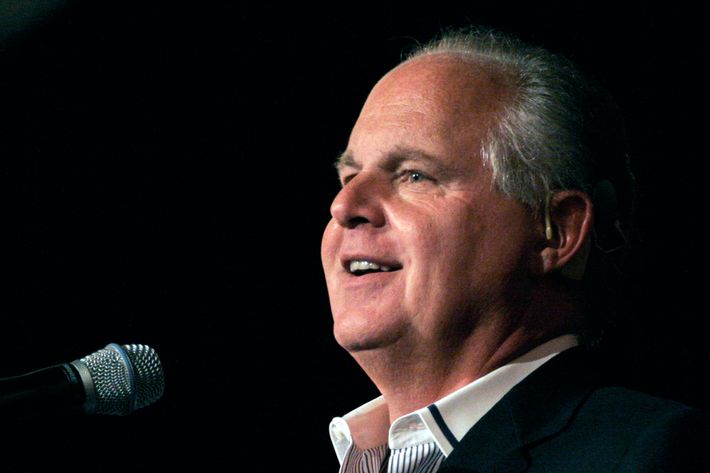

My fear turned out to be unjustified. Nobody paid much attention to what Obama said. The only real attention the passage received came from conservatives, who quoted the first line and ignored all the other parts. The Wall Street Journal op-ed page and Rush Limbaugh, among others, repeated the first line incredulously. (Limbaugh: “’There’s no doubt that there’s some folks who just really dislike me because they don’t like the idea of a black president,’ Obama said in the article …” So, what, white Americans have just figured out Obama’s black in the last two years? This is classic.”) They heard the part that inflamed their self-righteousness, and blocked out all the rest.

Hair-trigger racial outrage does not reside solely on the right. The ambition of my essay is to describe how American politics in the age of Obama has become balkanized not along racial lines, but by how people think about race. Red America and blue America are opposing camps whose self-conception is rooted primarily in seemingly irreconcilable ideas about the state of racial justice. I also argue that those ideas are less irreconcilable than we think — that the blue-state belief that racism is deeply interwoven with conservatism, and the red-state belief that Democrats use race to delegitimize conservative ideas — can both be true.

Of course, to describe this fault line is also, inevitably, to inhabit it. And the reactions to the article so comfortably fit within my thesis that they could have been used as case studies in the article itself.

Robert Tracinski of the Federalist responds to my analysis of conservative racial thought (almost entirely ignoring my analysis of liberal racial thought) by reiterating the familiar themes: “racism” is primarily a tactic to distract from liberal failure; there’s no political lineage between the anti-government ideology of white southern conservatives before the mid-1960s and the anti-government ideology of white southern conservatives today; racial disunity is entirely the fault of liberals. I did not have space in my story to rebut the elaborate revisionist conservative historical account, but I wrote a longer treatment here.

Since I’m at least somewhat liberal, the most provocative portion of my argument is its expression of partial sympathy with the right. Like Obama, I believe liberals unfairly dismiss conservative ideas out of hand due to their historic associations. Unlike Obama, I have the time and space to cite several examples. The liberals I described include figures I like, admire, and have important professional relationships with.

Jamelle Bouie at Slate has written a reply that he presents as a rebuttal to my essay, but which mainly just elides it. According to Bouie, the article describes “a low-stakes cocktail party argument between white liberals and white conservatives.” That is flatly inaccurate — the essay describes not only elite opinion but also important changes in mass public opinion, both anecdotally (through man-on-the-street quotes) and through Michael Tesler’s study of the survey data. The trend I describe is a reordering of the way 300 million Americans think about politics, splitting America into opposing factions that identify not by race, but by how they think about race. One might disagree with my analysis or the research that undergirds it, but to describe this as a “low-stakes cocktail party argument” is bizarre.

Bouie likewise argues that my essay ignores black Americans. This is also untrue — it quotes several. What’s true is that it does treat black Americans as part of a red-blue partisan divide, as opposed to treating them as black Americans, per se. That’s why I wrote an essay about American politics. It’s also because the explicit thesis of the essay is that that the Obama era has produced a cleavage along ideological rather than racial lines (as embodied, for instance, by the way the Zimmerman trial produced an ideologically polarized reaction, in contrast to the racially polarized reaction to the O.J. Simpson trial.) Bouie chastises me for ignoring “race as experienced in the ‘day-to-day’ lives of ordinary people,” and argues that I should instead have written about how “a twentysomething black New Yorker” would perceive “the patrol car that trails her teenage brother when he rides his bike to the corner store.” The state of black America under Obama is a fantastic subject for an article. It is not, however, the subject of this particular article. “I wish you had written your article on a different topic” is understandable as an expression of discomfort, but it’s very strange as a form of analysis.

The Washington Monthly’s Ed Kilgore, in a trio of posts, objects that it is perfectly fair to impute racism to conservative policies that have a “disparate impact” on African-Americans, citing Republican opposition to things like health-care reform. “I’m willing to stop ‘playing’ the ‘race card,’ accurate as it often is,” he writes, “if conservatives are willing to reflect more on a fundamental inability to accept the equality — not of some abstract quantity called ‘opportunity,’ but of access to the basic necessities of life in this rich society.” If Republicans want Kilgore not to assume they are racist, all they need to do is agree to the liberal policy agenda, or perhaps something close to it.

And Kilgore is right, of course, that Republican policies tend to enrich a disproportionately white constituency and harm a disproportionately nonwhite one. He thus deems the question of motive irrelevant. But suppose we lived in a world where Democrats wanted to redistribute even more resources from the (disproportionately white) rich to the (disproportionately nonwhite) working-class and poor. At some point, the level of redistribution could be high enough that Kilgore himself would object — say, a federal government consuming one third, or one half, or two thirds, of the economy. Would it be fair to describe his agenda as objectively racist? Would that free Kilgore’s left-wing critics from taking his stated objections at face value?

The most problematic part of Kilgore’s argument is his recurrent phrase “objectively racist.” It consciously or unconsciously harkens back to a chilling Cold War-era line used by conservatives, who described their domestic opponents as “objectively pro-Communist.” Their underlying logic, like the phrase itself, mirrored Kilgore’s: if you opposed the conservative foreign policy agenda, the “objective” thrust of your beliefs aided communism. This line of reasoning conveniently enabled conservatives to rhetorically lump together all their domestic opponents under the broad rubric of “pro-communist,” insinuating a poisonous motive while freeing themselves from having to demonstrate it.

Salon’s Joan Walsh does identify as her objection my criticism of liberals, but then spits out a wild array of contradictory responses. Lawyers call the technique used here by Walsh “arguing in the alternative” (i.e., It’s my vase. It was broken when you gave it to me. It was in perfect shape when I gave it back. I’ve never seen that vase before in my life.) Walsh concedes, “I’m sure there are instances Chait can find where MSNBC hosts and guests (including me) went too far with racial rhetoric,” as if this were a hypothetical rather than a phenomenon I showed in considerable detail. Also, she says, it’s fine for liberals to assume racism lurks behind everything Republicans do because “Race has been behind GOP opposition to white politicians, not just black ones, who favor civil rights” — which is to say, racism explains the motives of basically all partisan Republican behavior. Also, if liberals stopped unfairly impugning Republicans, it wouldn’t matter. (“What would change? Would the Republican Party drop its opposition to anything President Obama supports?”) Also, liberals just shouldn’t care in general about being fair to conservatives. (“If that hurts Jonah Goldberg’s feelings – yes, Chait would have us feel sad for Jonah Goldberg, not just Bill Kristol – sorry, but I’m not losing sleep over it.”)

Walsh has supplied an apt demonstration of the problem I am describing. The very idea that liberals should be bound by some standard of fairness when assigning racist motives to conservatives strikes her as outrageous. Walsh is not alone in her disregard for fairness. In another Salon piece running today, Brittney Cooper ferrets out the alleged racial insensitivity of writer Michelle Goldberg. (Salon is on a roll.) According to Cooper, Goldberg’s plea for reason is itself an act of quasi-racism. (“the demand to be reasonable is a disingenuous demand. Black folks have been reasoning with white people forever. Racism is unreasonable, and that means reason has limited currency in the fight against it.”) A few years ago, Melissa Harris-Perry — in a column ironically accusing Joan Walsh herself of racism — argued that those accused of racism should be considered guilty until proven innocent. “I am baffled by the idea that non-racism would be the presumption and that it is racial bias which must be proved beyond reasonable doubt,” she wrote. “If anything, racial bias, not racial innocence is the better presumption when approaching American political decision-making.” Just how a person so accused could overcome the presumption of racism, Harris-Perry did not explain.

A huge proportion of these intra-left debates concern establishing the boundaries of precisely when and how one liberal can fairly accuse another of racism. When it comes to making such accusations against conservatives, do liberals have any evidentiary standards at all? Reading the liberal objections to my piece, I fail to detect any.

The question of setting fair boundaries for debate may not be as important a problem as racism, but it is a major problem for the left. It also happens to be the problem that gave rise to Obama’s political career. The president’s transformation from regular student to national figure began at the Harvard Law Review, then torn bitterly between over race and what everybody called “political correctness.” In 1990, Obama was elected the first black president of the Harvard Law Review, and thus made the subject of national news coverage, because he alone was able to understand the perspective of both enemy camps.