Four years ago, President Obama gathered leaders from both parties in a cavernous room in Blair House to undertake a televised debate-cum-negotiation over health-care policy. The reason for this unusual political theater was that political fervor had overwhelmed what was supposed to be a fundamentally technocratic process of designing programmatic changes to fulfill agreed-upon goals. This was the last, best attempt to redeem a basic promise of his candidacy — that the irrational elements of politics were unnecessary vestiges, that reason could drive out passion. In his opening remarks, one can see Obama’s once-certain conviction reduced to a wan hope:

And unfortunately over the course of the year, despite all the hearings that took place and all the negotiations that took place and people on both sides of the aisle worked long and hard on this issue and — this became a very ideological battle. It became a very partisan battle. And politics I think ended up trumping practical common sense …

What I’m hoping to accomplish today is for everybody to focus not just on where we differ, but focus on where we agree, because there actually is some significant agreement on a host of issues …

My hope in the several hours that we’re going to be here today, that in each section that we’re going to discuss — how do we lower costs for families and small businesses, how do we make sure that the insurance market works for people, how do we make sure that we are dealing with the long-term deficits, how do we make sure that people who don’t have coverage can get coverage — in each of these areas, what I’m going to do is I’m going to start off by saying, here are some things we agree on. And then let’s talk about some areas where we disagree, and see if we can bridge those gaps.

Of course Obama’s Blair House wonkfest came to tears, as everybody by then already expected it would, and in short order he began the transition to framing his differences with Republicans in more straightforwardly ideological terms. That original spirit has returned, though — not in electoral politics, but in journalism. Vox.com, FiveThirtyEight, and the Upshot (the New York Times’ forthcoming data-analytic journalism site) all promise, in one form or another, an ethos of empiricism that can be insulated from politics. As Vox.com editor Ezra Klein argued in a manifesto of sorts timed with his publication’s launch, “politics makes us stupid.”

The empiricists may not be interested in politics, but politics is interested in them. The data journalism movement in general, and Klein’s project in particular, has spurred a fierce ideological backlash. A series of critics, mostly from the right, but also from the left, have flayed their claim of disinterested expertise as as disingenuous cover. “If the voter’s life experiences or intuition tells him that a government bureaucracy will create an inferior health care experience,” argues David Harsanyi in the Federalist, “there’s no chart that’s going to change his mind.”

It is a depressing response, but also one that proves its own point. Reliance on empiricism offers no escape from ideology because, in American politics, reliance on empiricism is an ideology.

***

The hope that disinterested experts might guide our public-policy debates was a foundational belief of the progressive movement a century ago. Laissez-faire ideology did not require empirical confirmation — conservatives regarded the free market as both self-correcting and a perfect moral arbiter of social value. It was activist government that required an army of nerds to measure its success. “If the scientific temper were as much a part of us as the faltering ethics we now absorb in our childhood, then we might hope to face our problems with something like assurance,” wrote the progressive intellectual Walter Lippmann 100 years ago.

The spreading managerial bureaucracy in government, and the rise of private counterparts like the Brookings Institution, all reflected the distinctly progressive faith in social science. It’s important that the implicit premise of social science is the elevation of measurable outcomes, not abstract rights. When an early Brookings study angered coal-mine operators by endorsing nationalization, the Brookings president shot back, “We are concerned only in finding out what will promote the general welfare.” Using economic policy to promote the general welfare sounds neutral, but it presupposes that market incomes are not sacrosanct.

That ideological divide remains in full force today, when Republicans are pushing a bill that would impose a 40 percent cut to funding for social, behavioral, and economic sciences.

The scale of the divide was placed on vivid display during the 2012 election, when Silver — attempting to measure the ideologically neutral question of who would win the election — nonetheless became a partisan flash point. With various levels of sophistication, conservatives mounted their own critiques ranging from the philosophical (Jonah Goldberg: “the soul — particularly when multiplied into the complexity of a society — is not so easily number-crunched”) to the quasi-scientific (Sean Trende and Jay Cost leaned heavily on the term “bimodal distribution” to arrive at dramatically cheerier prognoses for Mitt Romney). The poll-unskewing movement infected mainstream reporters and commentators, many of whom declared the election a toss-up.

The longer-running conflict, and the one that in many ways showcases the bitter empiricist divisions of the Obama era, concerns health-care reform. On the surface, the war over the fate of Obamacare merely pits opposing wonks arguing the finer points of social-science methodology. In reality, it shares many of the same qualities as the great poll-unskewing battle of 2012.

Few people remember anymore, but the moment that rocketed Paul Ryan to his status as thought leader of the Republican Party was a soliloquy he delivered at the Blair House summit. All sides had expected Obama to dominate the debate, but Ryan forcefully rebutted all the budgetary assumptions undergirding the health-care bill. Speaking in relentlessly technocratic terms, Ryan asserted, “the bill does not control costs, the bill does not reduce deficits,” and rattled off a series of bullet points that bolstered, or seemed to bolster, his point. The Wall Street Journal editorial page reprinted his remarks. The YouTube clip of the confrontation attracted over a million views. Ecstatic conservatives declared Ryan the obvious victor and began touting him as presidential timber.

In fact, Ryan’s argument was wildly and often amateurishly wrong. The bill was “full of gimmicks and smoke and mirrors,” Ryan lectured. It would turn out to increase rather than reduce the deficit. It paid for ten years of spending with six years of pay-fors! It relied on phantasmal cuts to physician pay to cover the cost of new insurance subsidies! These were not merely different interpretations of ambiguous evidence, or even exaggerations — they were utter nonsense, but well at home among the kinds of analysis circulating among leading Republican health-care wonks.

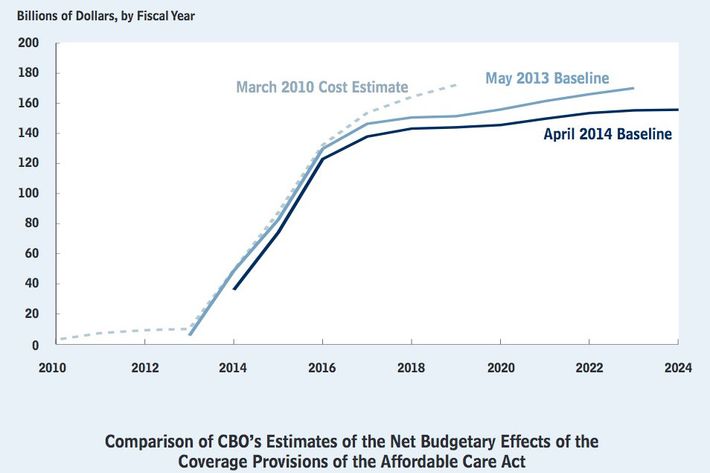

There will never be a single dramatic moment that will shatter the right’s inbred health-care falsehoods the way the election, in a single night, discredited the poll-unskewers. But the Congressional Budget Office’s update on Obamacare issued last week is the latest and most powerful repudiation of the case Ryan and his allies made. It reiterates that, contrary to the right’s certainty that the apparent deficit-reducing measures would melt away as the program went online, it still reduces the deficit. Indeed, it turns out to be even more fiscally conservative than originally forecast. Every new forecast turns out to be more optimistic than the last.

Of course, the prophecies of doom have not gone away. They have simply been replaced by an endless parade of new doomsaying — and when those predictions are not borne out, the day of reckoning is shifted farther and farther back in time. A few months ago, conservatives giddily predicted the website might never be fixed, and Obamacare would fail to operate at all, or be repealed by Congress before the midterms. Later they predicted too few people would enroll. (Enrollment exceeded predictions.)

They have more recently placed their hopes in the prospect that rates would skyrocket and insurers would pull out of the marketplaces. Insurers in fact predict the opposite: “Around the country, insurers are considering expanding their stake in the Obamacare exchanges next year, bringing their business to more states and counties. Some health plans that skipped the new marketplaces altogether this year are ready to dive in next year.” The Society of Actuaries likewise projects premiums to fall one to two percentage points lower than the rate they did before Obamacare.

This is the backdrop against which Klein wrote a story concluding that Obama’s health-care law is working more or less as intended, triggering a wave of indignation and ridicule on the right. This was all the proof conservatives needed that Vox’s claim to studious empiricism was merely a cover to smuggle in liberal propaganda.

The truth is that if you followed coverage by Klein, or Jonathan Cohn (who is starting a policy vertical at the New Republic), or Sarah Kliff, you you have gotten an account of Obamacare’s successes and failures as accurate as Silver’s account of the campaign horse race. If you have followed analysts on the right, even the best-informed ones, you have wallowed in a world of self-delusion.

The fervent conservative insistence that the law would fail to achieve its goals was not an opening to find different and better ways to meet those goals. It was an expression of a deeper disagreement with the goals themselves, a theological opposition to bigger government. The conservative premise, that larger government per se impinges on freedom, has no parallel among liberals, who support larger government only if it can be demonstrated to fulfill particular goals.

Only one side of the debate cared about accurate empirical measures of the health-care law, because only one side hinged its view of the law on whether it actually worked. Evaluating health care, or other government programs, by objective criteria sounds perfectly neutral. But to do so is to disregard the deep moral belief held by most conservatives that big government is inherently wrong. The empirical evenhandedness of the new data journalists is a wonderful contribution to American public life. It is, however, anything but politically neutral.