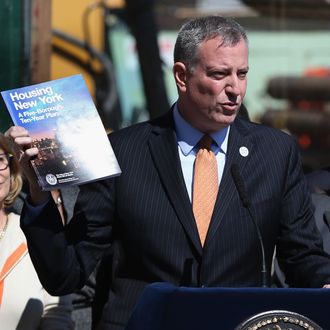

As a document of progressive aspirations, Bill de Blasio’s new housing plan is a beautiful thing. The 117-page report envisions a future in which seniors can stay put without fear of eviction, packed families can finally spread out, New York apartments get even more efficiently tiny, the homeless are given roofs of their own, and everyone who comes here can afford to stay. It’s exciting to see a new mayor throw the full weight of his office at the city’s most urgent problem: The rent is too damn high. This is more than just an economic document. De Blasio sees his housing plan as a tool to help desegregate the city, keep neighborhoods more stable but also mix up its income groups, and keep the middle class from spinning out into the inner-ring suburbs.

As my colleague Chris Smith discussed yesterday, the mayor is pumping real money into his immensely ambitious proposal: $8 billion in city funds that, multiplied by private investment and topped out with federal grants, should produce a $41 billion program, the largest ever. He’s baring some technocratic teeth, too: In many neighborhoods, private developers will be forced, not just politely asked, to include rent-regulated apartments in new buildings. He’s tailored policy to his dreams of lifting the poor: Subsidies tilt heavily towards the lower end of the economic spectrum. And he’s set a firm quota by to judge his tenure: 80,000 new affordable units in ten years, plus 120,000 more “preserved” — prevented from slipping away into the unregulated market.

But for now, “Housing New York” is more of a wish list than a plan. It promises future nuance and detail, but glosses over oppositions that could pit neighbors against each other, turning de Blasio’s “two cities” into a fistful of splinters.

Speed versus Consensus. A tone of urgency runs through the report’s bureaucratic prose, a sense that the housing crisis is flaring out of control. But no mayor can build by decree. Exactly where all those new apartments will be, in what sort of buildings, who will put them up, and how soon — those details will have to hammered out block by block in zoning maps, community board meetings, public brawls, and innumerable delays.

Density versus Gentrification. The word gentrification doesn’t appear once in the report, but it haunts all the policy prescriptions. In a city that is running out of land, building more means building high. To accomplish this, the de Blasio administration needs the real-estate market to thrive, but developers gravitate to areas where prices are on the way up. New towers include some rent-regulated units, but the rest heat up the local market, making the neighborhood less affordable, rather than more.

Idealism versus Realism. As the report points out, New York has a million poor households that compete for the roughly 425,000 apartments that they can afford. Even if all of the 80,000 new subsidized apartments went to that slice of the population, that still wouldn’t come close to making the city a less expensive place to live.

Neighborhood Stability versus Desegregation. An adequate stock of affordable apartments can help people keep living in the area where they grew up, and keep a neighborhood’s ethnic character from flaking away. But de Blasio has a conflicting goal, too: He sees his housing policy as a tool to help desegregate the city, mix up its income groups, and keep the middle class from spinning out to the inner-ring suburbs. How can you simultaneously encourage neighborhoods to change and also keep the same?

The Needy versus the Needier. The plan wisely addresses the epidemic in homelessness by emphasizing permanent supportive housing rather than emergency shelters. But it also hopes to foster a middle-class city that welcomes artists, houses more cops, and cuts down on teachers’ killer commutes. But subsidies are a zero-sum game, and one segment or another is bound to feel shortchanged. In fact, maybe all of them will.

Quantity versus Quality. Another word missing from the report is architecture. Unless design becomes a priority, the focus on building at a faster clip will produce a blight of shoddy uniformity that serves all of New York’s varied populations equally badly.