Earlier this year, when I wrote about the emerging political consciousness of Silicon Valley, I didn’t mention Rand Paul at all. Partly, I omitted Paul’s name because, despite the airtime given to a few prominent libertarians like Peter Thiel, the tech industry still remains an overwhelmingly liberal stronghold, with the vast preponderance of campaign donations and votes going to Democratic candidates. And partly, I just didn’t think Paul’s overture to tech companies would work — Paul’s anti-surveillance shtick might appeal to privacy zealots, but Bay Area social progressives would reject his more extreme fiscal and foreign-policy views out of hand.

I may turn out to be wrong. Today, Paul appears to be making a full-court press for the affections of Silicon Valley, and there are some signs that his efforts are paying off.

At last week’s Sun Valley conference, Paul had one-on-one meetings with Thiel and Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg. The former isn’t surprising. (Thiel basically bankrolled the elder Paul’s 2012 presidential campaign.) But Zuckerberg is an unlikely Paul ally. He’s clearly not a down-the-line Democrat — he held a fund-raiser for Chris Christie, and his meandering political organization, FWD.us, has backed conservative politicians — and, when asked about his affiliation, he has refused to identify with either major party, saying only, “I’m pro-knowledge economy.” But he hasn’t come out as a tea-party conservative, or anything like one.

Sean Parker, another Facebook-affiliated billionaire and politically active tech investor, has also met privately with Paul. Parker is undergoing his own political rebirth, shifting from backing mostly progressive causes and politicians to writing checks to centrist conservatives as well. Last quarter, he gave more than half a million dollars to GOP groups and candidates, making the case that ideology trumps party affiliation when it comes to making progress on issues like immigration and campaign-finance reform.

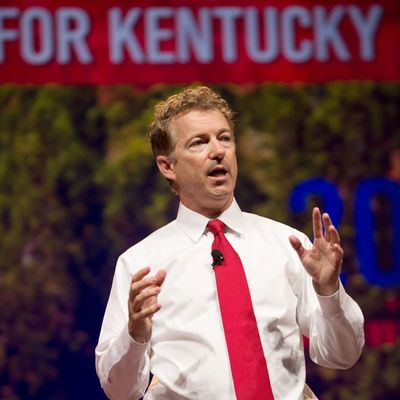

It’s friends like Parker and Zuckerberg who explain why Paul now routinely receives what Fortune called a “hero’s welcome” when he comes to Silicon Valley. Next weekend, Paul will get to make his case yet again as the keynote speaker at Reboot, a San Francisco conference put on by a group called Lincoln Labs, which self-defines as “techies and politicos who believe in promoting liberty with technology.” He’ll likely say a version of what he’s said before: that Silicon Valley’s innovative potential can be best unlocked in an environment with minimal government intrusion in the forms of surveillance, corporate taxes, and regulation. “I see almost unlimited potential for us in Silicon Valley,” Paul has said, with “us” meaning libertarians.

He’s not wrong. Today’s Silicon Valley is still exceedingly liberal on social issues. But it seems more skeptical about taxes and business regulation than at any point in its recent history. Part of this is due to the rise of companies like Uber and Tesla Motors, blazing-hot start-ups that have been opposed at every turn by protectionist regulators and trade unions, in confrontations that are being used by small-government conservatives as case studies in government control run amok. (“Government intervention is unnecessary, counterproductive, and immoral,” wrote Derek Khanna in the American Conservative in May, lassoing the cases of Uber and Tesla into his call for a more innovation-friendly GOP.)

Even some of Paul’s more extreme views, like his offhand “I’m not a firm believer in democracy” comment, may be getting a hearing in today’s tech industry. Democracy, after all, gave us anti-drone laws, Sarbanes-Oxley, the 23andMe crackdown, and Healthcare.gov. Engineers hate the concept of “friction” — in product-design terms, anything that slows down or otherwise impedes a user’s experience — and what is democracy if not a system built for more friction? Paul’s new fans in tech may not follow him all the way to Galt’s Gulch, but they don’t necessarily have to — simply realizing that the values of libertarianism will allow them to carry out more of their pet projects unimpeded might be enough to tip them into his camp.

Paul’s biggest problem, to borrow a term popularized among tech workers, is that he’s not a “culture fit” in Silicon Valley. A gray-haired Kentucky ophthalmologist is a less obvious representative for tech’s political class than, say, Ro Khanna, an Indian-born 30-something who speaks easily about 3-D printing and robotics. But it’s not hard to imagine that someone with Paul’s political genotype and a different phenotype — younger, coastal, more fluent in tech-speak — could pick up broad support from the kinds of techies who want government to leave their start-ups alone.

The ideological overlay of Silicon Valley isn’t strictly political, after all. It’s more about how institutions are structured and functions are carried out. Lean and fast-moving are good. Bloated and deliberative are bad. “Permissionless innovation” is good. Bureaucratic box-checking is bad.

In this context, you can see why someone like Paul could appeal. And while it’s still possible that people like Zuckerberg and Parker could remain in the squishy political middle, it’s also possible that they could tip into anti-Establishment libertarianism, and take a whole coalition of tech donors with them. After all, what a certain Silicon Valley contingent wants most right now is independence. And few national politicians are prepared to lengthen the leash as much as Rand Paul.