In his public statements about the Dallas Ebola patient this week, the CDC’s director Thomas Frieden has been steady, optimistic, and reassuring. “We will stop Ebola in its tracks,” he has said. He has maintained that Americans should feel secure, that the systems of disease surveillance, isolation, and supportive care in place here are robust enough to keep Ebola from spreading widely. But in the horrifying news from West Africa, and in the anxious episodes in Dallas, we are beginning to learn a little bit more about what that security depends upon. It depends, here but mostly in West Africa, upon inhumanly heroic and terrible acts of bravery by medical workers putting themselves at risk in order to keep the disease from spreading.

Perhaps the most poignant story to emerge from the Ebola zone this week was that of Foday Galla, an ambulance crew chief in Monrovia, who explained to Time’s Aryn Baker how he had contracted Ebola and then — after two weeks of treatment — beat it. The story lies in how he became infected, and the risks he was willing to take to save others.

“Galla,” Baker writes, “knows exactly how he got sick.” He had been to the same house twice, to take seven infected family members to a hospital — a mother and father, three sons and a daughter, and a grandmother. All of them had died. A week later, he was called back to the same house: The lone survivor, a 4-year old boy named Samuel (who had been cared for by neighbors) was throwing up. Galla put on his protective gear. “All I wanted to do was save that little child’s life.”

Baker writes: “Galla found Samuel in a pool of vomit, and gathered him into his arms. The child vomited again, all over Galla’s protective suit. Ebola is spread by infected bodily fluids; vomit is particularly dangerous. ‘I didn’t care,’ says Galla. ‘All his family was gone, so I wanted to make sure he kept his life.’ Galla was in such a rush to get Samuel to treatment that he didn’t stop to disinfect with a whole-body chlorine spray. Samuel survived. But two days later, Galla started feeling sick.”

This week, public-health officials in Dallas struggled to find a health-care worker willing to go into the apartment where the Dallas Ebola patient, Thomas Duncan, had been staying in order to remove the towels and sheets he had used, to protect the family that is still living there. (This morning, finally, a Hazmat team entered.) It seems a little crazy, given what Galla and many others like him are doing in West Africa, that it took the better part of a week for a Hazmat team to be prevailed upon to enter. But it also exactly shows how much a policy of containment requires of the workers who enforce it. Even in the United States (as was made obvious earlier this week, when it turned out that Duncan had initially been sent home from the hospital because a nurse failed to communicate the news that he had recently been in Africa to the rest of her medical team) the system of isolation and surveillance puts incredible stress on every medical worker to get it right.

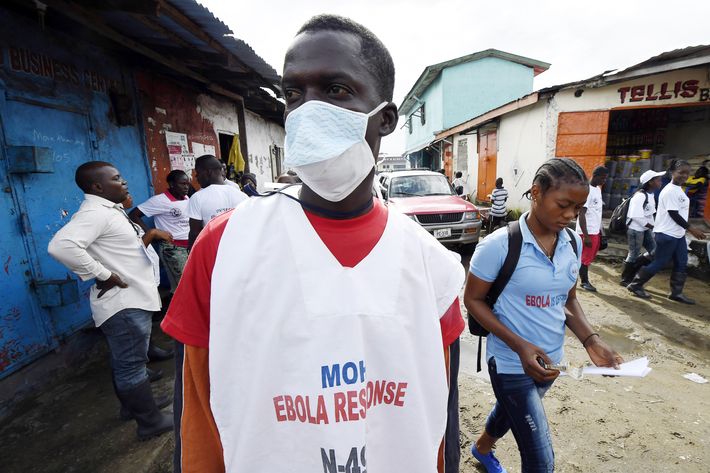

In West Africa so much more is asked of these workers, both because the lack of medical resources means they must take much greater risks themselves and because the acts required to impose isolation on an infected population are much more terrible.

At a hospital in Sierra Leone this week, the Times reporter Adam Nossiter watched a 4-year old girl, still alive, lying on the floor in a puddle urine, with two corpses lying nearby. A worker came through and sprayed her body with chlorine; that was all he could do. In Liberia in August, riot police had to physically seal off a slum of 50,000 (using scrap wood and barbed wire) to try to keep the infected from leaving, even as the slum’s residents rioted to try to get out. In a long report on the challenges involved in getting U.S.-financed Ebola hospitals up and running in Liberia, the Times’ Helene Cooper watched as emergency workers directed a sick 9-year-old boy to sit alone on a plastic chair, separated from the staff by “10 feet and a plastic barrier.” Three of his relatives had already died, he said. Cooper writes, “he looked small and frightened.”

These are unspeakable acts. They are also heroic ones. There are the health risks that these workers incur: As of September 22, according to the WHO, 348 health-care workers were known to have contracted Ebola, and 186 of them have died. But there is also the simple human awfulness at having to pen off a 9-year-old boy, or seal off a neighborhood, or spray a dying 4-year-old girl with chlorine because there is nothing else that you can do for her.

It has been possible, even as news about the horrors in Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone have mounted, to remain relatively sanguine about the disease in the United States. We are, as Frieden keeps reminding us, relatively safe here, shielded by a vast and secure network composed of doctors and nurses and the systems of modern medicine. And yet it is humbling, and horrifying, to realize what that system looks like from the inside, what ambulance workers and doctors and nurses have to put themselves through, especially in West Africa, so that the rest of us might live.