Babysitting the Bomb: Meet the Missileers Who Watch Over America’s Nuclear Arsenal

It’s aging, fussy, and watched over by some very alert military officers in the middle of nowhere.<br /><br />

The Air Force has bolted a large sign to the fence of the Alpha-01 Missile Alert Facility, clear white type announcing to any wayward traveler that this little patch of desolate Wyoming prairie belongs to the 319th Missile Squadron, 90th Missile Wing, Global Strike Command. A sergeant stands at attention behind the gate. An American flag is snapping violently at its mast, but the sergeant’s billed cap, high at the top of his head, is perfectly still. He takes my ID through the fence and disappears into what looks like a little house. When he returns, he hands it back. I have been told that he is going to ask “What is your status?,” which he does, and I have been told that I am to answer “I am all secure,” and that if I answer with any other phrase or make no answer at all, I will be thrown to the ground and handcuffed. (“Nothing to do but hold your ID above your head and wait for the pain,” one of the maintenance guys back on base had told me.) I tell the sergeant I am all secure. The gate opens skyward, we step in, and it closes again like a guillotine.

One hundred and fifty nuclear missiles live in the ground in the high plains outside Cheyenne, Wyoming, scattered across an unpopulated area the size of Houston. Alpha-01 controls ten of them. Buried directly beneath the Missile Alert Facility is the cramped capsule where pairs of officers, called missileers, keep watch over the weapons. It’s late morning, and I’m here to meet the crew that will soon be coming off duty.

Behind the gate, the sergeant, Greg Hutchinson, opens up like an innkeeper. “Welcome to Alpha!” he says, shaking my hand and bending into the wind. He is lanky and fit, with a neat mustache. He leads me to the facility, which is in fact a house, if not exactly a home, offering basic comforts to Hutchinson and the handful of airmen who protect the property and its silos. In the living room are couches, a couple of TVs, a pool table. Two of the Security Forces troops — everyone just calls them cops — are sitting at little café tables doing homework for their correspondence courses. There is a commercial kitchen where a lone cook prepares meals off a diner-style menu. (Currently out of stock, a whiteboard warns, are meatballs, taco shells, yogurt, oranges, Dr Pepper.) Everywhere there are framed renderings of bald eagles.

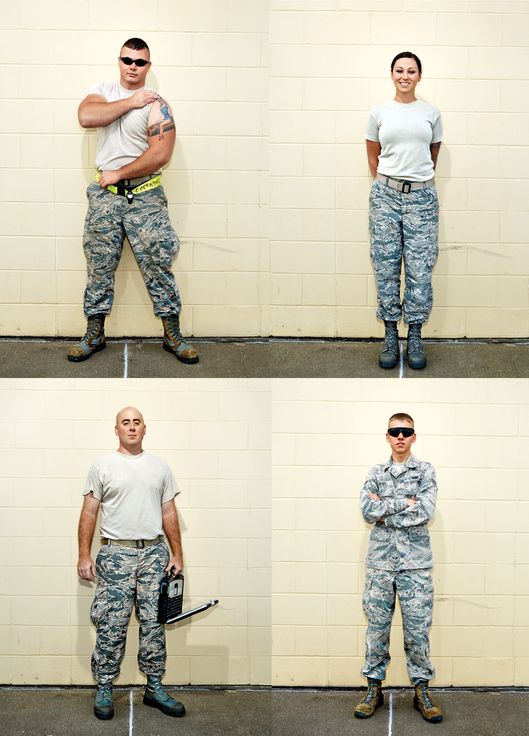

Sergeant Hutchinson is at once the installation’s superintendent, maintenance man, and most enthusiastic resident, and, cap and clipboard in hand, he shows me every room. Here is the gym with decals of football helmets lining the tops of the walls — “I’m a big football fan, so we decided to go with a little NFL theme in here” — and here is the electronics area, where the Dish Network box sits next to equipment that monitors the weather. Ducking outside, he shows me the barbecue grill and the basketball hoop, and then heads back in to show me his own spartan quarters, where the bed is made so neatly that it resembles a stick of chewing gum in its wrapper. In every room you can hear the moan of the wind against brick.

The tour stops before a sturdy door that only unlocks from within. Somewhere beyond it is an elevator descending 80 feet to the Launch Control Center. Two officers disappear behind the door to begin their shift, called an alert; it is supposed to last 24 hours but in case of bad snow or other emergencies can last as long as three days.

It is a clear early-fall day, though, and the old crew emerges as scheduled, blinking in the sunlight. Captain Jessica Gelsomino, 26, with dark hair pulled back and plastic-frame glasses, lugs a locked Pelican case filled with codebooks and authenticators. Her boyish deputy commander, Lieutenant Zachary Averett, follows. Both wear zipped-up flight suits, a grinning skull and pair of bombs staring out from their shoulder patches. Ordinarily, they would drive themselves the hour back to F.E. Warren Air Force Base in Cheyenne. Today, they have agreed to sit and have lunch with me.

It has been, as usual, a taxing alert. The missiles assail their handlers with “status” alarms indicating an internal temperature reading that’s too high, or a malfunction with the onboard guidance equipment, or a breakdown in the communications link with the capsule, or any number of aches and pains that might distress a Reagan-era warhead. During this alert, one of the missiles reported a GMR-26 — harmful fluctuations in its power supply — and began shutting itself down in response. “The weapons system is getting old,” Gelsomino says, picking at a chicken breast and vegetables that have been kept warm for her under plastic wrap. “And every day we get tested. Like, is this missile going to try to get away by itself? And we have to respond crazy-rapidly to ensure coverage of these sorties” — missiles — “so that they’re not sitting out there basically not talking to us.”

At the nuclear program’s peak in 1967, according to weapons analyst Stephen Schwartz, the U.S. maintained 1,054 operational missiles. We have since whittled down our arsenal in a cautious two-step with the Russians; now 450 Minuteman IIIs — the grandchildren of the long-range rockets devised by the Air Force during our Cold War hysteria — are on alert across the American West, divided among bases in Wyoming, Montana, and North Dakota. Still, the raw number is almost bafflingly high, especially when you consider that missiles are only one arm of our “nuclear triad”: America also maintains a strategic-bomber fleet of B-2s and B-52s capable of dropping nuclear gravity bombs and firing cruise missiles, as well as 14 nuclear submarines, each of which carries 24 submarine-launched missiles packing up to five independently targetable warheads. Across the triad’s platforms, we have an estimated 2,120 deployed nuclear weapons, some of which are significantly more powerful than those aboard the Minuteman. If a single sub-launched W-88 warhead landed at Broadway and Houston, it would collapse buildings from Central Park to Brooklyn’s Barclays Center; radiation would give third-degree burns to people in Jersey City.

Bombers fly nonnuclear missions and sub crews at least get to sail, but the missileers exist in a world apart, suspended in time in their holes in the ground, counting the hours. Many have complained of a lack of career-advancement options, poor leadership, and badly outdated equipment. In January of last year, reports surfaced that launch officers at Malmstrom Air Force Base in Montana had been sharing answers for their thrice-monthly proficiency tests. As the revelations unfolded, the Air Force fired the cheating officers, installed a new general to oversee the three missile bases, and made a slate of improvements, including changing the exams to pass-fail. The problem may be harder to fix, though: Last week, a report from Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel condemned the “blurring of the lines between accountability and perfection” and announced that billions more in immediate spending was needed to keep the crumbling nuclear enterprise running.

Averett bites into what the menu calls the Monterrey Chicken Sandwich. He explains that the work is even harder because there are no cameras on the weapons; they can only transmit information through alphanumeric codes. “You’re blind,” Averett says. “You have no idea what’s going on out there. So you see what your weapons system is telling you, and you try to interpret that the best you can.”

I ask Gelsomino if launch officers talk to their missiles the way we might talk to our pets. She pauses for a moment. “I think it’s mostly just like an annoying kid that’s just yelling at you — and you have to figure out how to appease it, and what it’s trying to say, because it can’t talk yet.” They both laugh.

Averett jumps in: “Some of the kids are good. They’re over in the corner, and they’re being quiet. And other ones are literally yelling at you.”

“There is stuff happening every day and crazy alerts,” Gelsomino says. “It’s nothing we’re going to go to war over — it’s just, you know, the president wants to know his missiles are being looked after. And that’s what we do.”

Nobody truly thinks we need 2,120 deployed nuclear warheads — if we need any at all — and when he came to office, it seemed like pragmatic, dovish Barack Obama might finally consign the program to history. In April 2009, just months into his presidency, he gave a speech on nuclear disarmament to a cheering throng in Prague, saying, “Today, I state clearly and with conviction America’s commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons.” A year later, he signed New START, a next-generation arms treaty with the Russian government, which calls for reductions in deployments to 700 bombers, intercontinental ballistic missiles, and sub-launched missiles on each side and limits the overall number of deployed warheads to 1,550. But it’s highly unlikely that the United States will go any further than the treaty, superiority in the missile game having been a sacred tenet of our foreign policy since the 1950s. The reascendancy of Vladimir Putin and Russian aggression (throw in North Korea’s and Iran’s nuclear intentions) hasn’t helped: Denuclearization now looks both like bad politics and bad policy.

So missileers must prepare for the worst. The headquarters of the 90th Operations Group, where the missile-launch crews train, is a modest stucco building that could easily be repurposed as an elementary school or a senior center. It sits in grassy parkland, and the base’s population of tame antelope nibble at the ground cover and rub their antlers against the trees. Inside, photo-collages praising the excellence of the staff dot the hallways. At the end of one of these corridors, past the officers chatting with their Starbucks cups in hand, is the Missile Procedures Trainer.

The Trainer, or MPT, is a replica of the underground Launch Control Centers out in the field, and this is where the missileers get as close as they ever will, most likely, to staging a nuclear attack. First Lieutenant Cory Elder is seated in the contoured commander’s seat in front of a control console the size of a Fiat. There is a clackety keyboard and a trackball and two ungenerous four-color screens displaying grids and numerals. Beneath the screens are arrays of mid-century knobs and square buttons that light up from behind. One of the knobs is labeled WAR PLAN and toggles between positions marked A and B.

Pointing to the onscreen grid, Elder explains how a launch order would come through with an “enable” code for each missile, how it would be authenticated by the two-man Missile Combat Crew, and how a second team in the field would have to give their own “votes” for launch. He speaks for the missile: “I’m ready to leave. Do I have enough votes?” Once the proper affirmatives have come through from the rest of the squadron, dummy text appears, part of the script for visitors who don’t have the proper clearance to see the real orders. It reads: “Launch all intercontinental ballistic missiles asap.”

“Ready?” Elder says to his deputy commander seated at a twin console to his right. Each puts his two hands on two switches, all of which must be turned simultaneously. “Turn,” says Elder, and they twist their hands to the right. “ ‘Okay, I’ll leave now,’ ” he says in his missile voice. “And by ‘leave’ I mean, ‘Go murder people.’”

He is trying to be funny. He is also possibly a little bit loopy: It is not yet 8 a.m., and he and the deputy have already been in the trainer for four hours, reckoning with the end of the world over and over again. Crews call this “taking a ride.” A senior officer tells me the rides are designed to tear commander from deputy and push both deep into the adrenaline and stress and beeping-alarm din of a theoretical war order. “They’re bad days — very bad days,” one lieutenant tells me outside the trainer, nodding grimly.

“It’s fun, because we know it’s pretend,” says another missileer emerging from a ride of her own. “It would be a lot scarier if it were real.”

Could it ever be real? The question seems to haunt every wry joke, sour every declaration of Yes, sir, I would do my job if it came to it, no question. It could happen. A nuclear strike from a rogue nation desperate to make history, maybe. An act of sabotage inside our own nuclear architecture. A conventional attack against our strategic-bomber and submarine bases. A human or mechanical error at a Russian launch facility. A so-called catalytic war, in which a third-party power stages an attack meant to provoke two others into mutual destruction.

To the missileers in the Launch Control Center, it would likely all look the same: first, an Emergency Action Message from the president. Consulting their codebooks, the commander and deputy translate the message and read the resulting launch order aloud, detailing how many of their missiles they are to unleash. After confirming the order with the other capsules, they put their hands on their knobs, count down, and turn. The launch signal travels over buried cable, in some cases miles long, to each Launch Facility, where it initiates an explosive charge that dislodges the 110-ton silo door. The rocket below is now exposed to the sky. Within 30 seconds it sheds its umbilical cord and takes to the air, all 80,000 pounds, in a blinding flash of ignition.

The missile is 60 feet tall, 5.5 feet wide, and burns solid fuel. Twenty seconds after launch, it is 8,300 feet in the air and traveling more than 1,000 feet per second; by 40 seconds, it is at 38,000 feet and has tripled its velocity. When its third and final rocket stage burns out and falls away, the missile’s armed tip reaches 15,000 miles per hour, about 23 times the speed of sound. At that rate, it can hit any point on the globe in half an hour — “Guaranteed within 30 minutes or your next one’s free,” as the missileers’ boast goes. When the warhead reaches its target, a plutonium trigger sets off a fusion reaction in its fuel core, releasing 20 times more explosive energy than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945.

Once launched, the missile is not recallable and its warhead cannot be disarmed. This is by design, so that no adversary will ever think a launch is a bluff. The reentry vehicle is guided by its own internal targeting computer and gyroscopes, meaning that even if our bases are subsequently wiped out by an enemy’s strike — even if the missileers are gone, and our cities are gone, and America is already a memory — our warheads will still reach their targets and explode.

At Uniform-01, the mock-up silo used for training by F. E. Warren’s missile-maintenance personnel, a five-man crew runs through the hyperregulated procedure of removing a Minuteman’s nose section. Two airmen in harnesses work down alongside the missile, two airmen wait in a specialized trailer that has been backed over the silo’s mouth, and a roving staff sergeant coordinates the action. As a safeguard against mischief, no one person is allowed to put his hands on the missile unobserved, so the men shout continuous confirmation to each other in the missile man’s patois: “Twoooos, twooooos, I got your twooos!” After 20 minutes, the trailer’s winch begins to wind and the pointed snout of the missile appears. “Comin’ up slow!” shouts the staff sergeant. By the end of the operation, the crew is breathing hard.

I pipe up with my questions about what it feels like to put so much work into something that we’ll likely never use, but the airmen just smile. “People mistakenly think that we show up every day and keep nukes on alert because we anticipate launching them,” says Senior Master Sergeant Brandon Otten, who runs the maintenance-team training program. His boots are propped on a steel cross section of the missile body stenciled with DOWNRANGE and a little arrow pointing upward. “These are doing their job,” he says, pointing to the missile nose. “Us keeping them ready to go — it’s not that we don’t ever get to use them. We use them every day.” The mission is the show of readiness. And the show of readiness is the mission.

Otten and the maintenance team have been practicing for an Air Force competition called Global Strike Challenge designed to show off exactly this point. The contest pits missile and air crews against each other: loading bombs into planes, dropping bombs out of planes, moving warheads around by forklift, fixing Minutemen. Competitions among the strategic forces have been held off and on since 1948, going by names like Olympic Arena, Giant Sword, Curtain Raiser, and Guardian Challenge. There was no event at all last year because of budget cuts, and everyone seems excited about its return. “Global Strike Challenge, it’s kind of an outward symptom of our inward pride,” Otten tells me. Elder, the missileer who showed me the launch procedure, is quoted in a press release from the base’s public-affairs office saying that the competition is a chance to show “that we are trustworthy and that we are on top of our game. That goes beyond the borders of the United States as well, to signal to everyone that we’re ready for you.”

At Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri, I watch one event in which the base’s munitions squadron — “Ammo,” for short — builds and loads conventional airdropped bombs. (The nuclear events were off-limits to journalists.) Katy Perry and Kanye West pump from a boom box, over which shouts of “Build that beautiful bomb!” and “Let’s go, Ammo — wooo!” can be heard. Observers from Global Strike Command linger at the fringe in red hard hats, keeping time on stopwatches. As the team works, a B-2, the military’s $2 billion stealth bomber, rolls down the runway, taking off on a training run, its silhouette a perfect horizontal teardrop. “That’s the sound of freedom right there!” one of the Ammo officers shouts as the bomber screams off into the sky. When the event concludes, the competitors gather for the unit cheer: “If you ain’t Ammo, you ain’t shit!”

Unlike their colleagues in the missile force, the bombers’ support crews see their handiwork in action fairly regularly: B-2s have flown combat missions over Kosovo, Iraq, and Afghanistan. In 2011, planes from Whiteman took out Muammar Qaddafi’s air force in its hangars in Libya. In his office inside the 509th Bomb Wing headquarters, Colonel Matt Brooks, the vice-commander, assures me that staying proficient in the nuclear mission is still a big part of what the force at Whiteman does. He notes that the Wing’s insignia, which hangs over the gates of the base and is painted on all the planes, is a winged mushroom cloud. “It’s a constant reminder for us,” he says. Brooks points to a model B-2 on the desk in front of him. “You look at that airplane there,” he says, “and it’s a strategic messaging platform to many, many adversaries.”

That morning at Alpha-01 in Wyoming, I had asked the missileers how often they think about what would happen during an incoming attack. The Minuteman missiles are sited in the emptiness of the western states intentionally, because if war were to come, the missile fields would be “sponges,” as Schwartz, the analyst, put it to me, absorbing the brunt of a nuclear strike meant to disarm us. “It’s just weird,” Captain Gelsomino said, finishing up her chicken breast, “because you know that you are their target. Whoever they are, they’re looking at you if something were to happen.” Gelsomino and Averett, her deputy commander, were at pains to make it clear how small a chance there is that this would ever occur. Trying to imagine the reality of it seems at once terrifying and a little absurd. “It just becomes kind of a movie kind of thing,” said Gelsomino. “Just kind of lightening it up a little bit, rather than just thinking, My gosh, I’m going to be trapped down here until I run out of food.”

“If we are doing our job,” Averett said, “the whole point is that we don’t have to get to that.” He has never actually seen an armed missile in person. “You can only see so much in your mind’s eye,” he said. “You still think about it. What if. You know? What if it happened right … now?”

After lunch, I surrendered my phone and my voice recorder, and Sergeant Hutchinson, the facility manager, led me through another secure door to the freight elevator that services the Launch Control Center. It is a long ride down: two minutes to descend the 80 feet, said Hutchinson, who’s timed it.

At the bottom, in a dim, vaulted hallway lit by a flashing red light, Lieutenant Chaz Demerath read me the mandatory safety briefing and then gestured for me to follow him back to the right, past a blast door weighing eight tons. The hallway narrowed to a low tunnel through six feet of concrete. “Watch your head,” Demerath said.

The tunnel ends at the dark, hollowed-out cavity in which the capsule hangs, mounted on giant shock absorbers. A gangway leads across the void, through what feels like night air, to the capsule’s glowing mouth. Inside it is lit harshly, like an airplane, and with the same audible hiss of ventilation. There is a little bed module, stacked with the new crew’s backpacks, and an airplane lavatory. Otherwise it is the trainer capsule, knob for knob. Demerath and his deputy, Lieutenant Charlene Gracia, were one hour into their 24-hour alert. “It takes a few alerts,” Demerath said, “before you stop feeling nervous pushing the buttons.”

Sergeant Hutchinson lent me his flashlight and let me pick my way along a little catwalk between the cavity wall and the capsule’s outer skin, where departing missileers have scrawled farewell messages. “You are your own worst enemy, and your own greatest asset,” says one.

The last thing Sergeant Hutchinson wanted to show me was the equipment room that would keep the capsule livable if the worst happened. He pointed out how the air vents at ground level would slam shut, and how the nuclear impact would spring a catch in the water duct, isolating a 500-gallon supply. If the crew were to survive the initial detonation, the missileers would have that water and some boxed meals stashed under the capsule floor to live on. After that, they’d have to try their luck hacking out through a sand-filled escape shaft, hoping that the immense heat from the explosion hadn’t turned the filler sand into glass. The escape process, like everything else, is governed by a checklist. “Safety rules always apply, even during war,” says one of the manuals.

There is no real plan for what Hutchinson would do if there were an attack on Alpha. One of the orders calls for him to descend to the equipment room and look after the diesel-powered backup generator, but he doesn’t think he’d get the chance. “I just tell the crews to let me know if it’s happening,” he said, “so I can go outside with a cigar, look up at the sky, and just watch ’em come in.”

*This article appears in the November 17, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.