This week, Daily Intel profiles five inventors with big ideas that could make life a little bit better and more interesting for everyone.

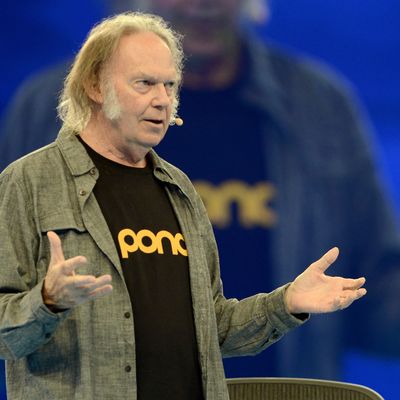

Rock legend Neil Young has a lot of noble dreams. He wants to end fracking, develop fuel-efficient electric cars, and protect the American family farmer, among other aims. The dream that he may be closest to turning into a reality, though, is his desire to change how we hear music.

Beginning in early 2015, Pono, a super high fidelity audioplayer developed by Young and a team of engineers, will become widely available. The player itself doesn’t look like anything special — it resembles a Toblerone — and its $399 price tag isn’t cheap, but the 69-year-old Young is hoping that delivering studio-quality sound in a portable package can reverse generations of bad-sound acclimation and usher in a future of higher audio standards.

Pono — the Hawaiian word for righteousness — debuted with a Kickstarter campaign last March, and the first units were delivered to backers just last month. Though the company, PonoMusic, officially launched back in 2012, Young’s mission to deliver better sound to a mass audience began back in the compact disc era. The problem, as the Pono team sees it (and without getting too technical), is that the analog tracks an artist creates in the studio are so complex and full of information that they needed to be compressed to fit onto a CD. That compression results in a loss of sonic substance, tone, and detail. “Once the world went to MP3s, it got ten times worse,” says Pedram Abrari, the executive vice-president of Pono. “You’re throwing away about 90 percent of the original analog data.” Abrari likens the resulting musical product to “a Xerox copy of the Mona Lisa.”

Despite his reputation for first-take, best-take thinking in the studio, Young had long been frustrated with the imperfection of digital sound. He made his opinion known to Steve Jobs, complaining that iTunes delivered tinny, diluted sound. The Apple co-founder, who himself allegedly preferred listening to vinyl records rather than his own company’s MP3 offerings, understood the musician’s gripes, but pointed out that he was in the business of selling convenience, not catering to audiophiles. He then posed a challenge to Young: You’ve got the money and influence, so why not start your own company?

So he did. But Young faced two key steps: Developing technology in such a way as to make a high-fidelity player both portable and affordable, and striking deals with record labels to acquire artists’ master tapes, from which Pono would source its music. Turns out that it’s good to be a rock icon: Young’s label, Warner, and fellow majors Sony and Universal, as well as a number of smaller, indie companies, quickly came onboard. The Pono team could then take the uncompressed recordings and convert them to the FLAC format, which stands for Free Lossless Audio Codec — that’s what plays on a Pono. Accordingly, the song files are massive. The Pono version of Young’s “Heart of Gold” takes up 205 MB of space; the iTunes MP3 version weighs in at 3.9 MB.

Two years ago, the New York Times’ David Carr visited Young at his California ranch and got a demo of Pono quality while sitting in the his host’s ‘78 El Dorado. “Right now, [Pono] needs a trunk full of gear,” Carr wrote. That’s no longer the case. Young teamed with a company named Ayre Acoustics to develop the handheld, non-trunk-size version. Abrari is cautious about revealing proprietary info about Pono, but he says that one of the secrets to its power is its specially designed circuitry, which — unlike an iPhone — doesn’t get distorted by apps, GPS, camera wiring, and, well, being a phone. Signal loss is not a problem. “Everything in your phone basically produces distortion into the audio,” says Abrari. “[Companies] jack up your music to make it as loud as possible and people perceive loudness as quality.”

Apart from relying on Young’s ears, and those of other demo-recipients like Bruce Springsteen, Jack White, and Rick Rubin, among others, the Pono team focus-grouped its product with audiophiles who’ve spent lavishly on their home systems. The comparisons between complicated home setups and the palm-size Pono were highly favorable, according to Abrari. The hope is that making sterling sonic quality convenient will shift listening habits and deepen consumers’ relationship with music. “The Pono movement,” Abrari says, “is meant to educate people about enjoyment they’re missing in their lives because they’re not getting the full music.”

Aural edification is one thing; cost, a very different other. There’s no way around it — getting the full measure of a Pono involves an investment beyond just the player itself. While Abrari says that listeners will notice a sharp improvement in sound quality even if they use cheap earbuds with their Pono, they’ll get “maximum enjoyment” if they shell out for “a pair of headphones in the $200 to 300 range.” Then there’s the fact that getting music on your Pono involves buying the FLAC files of songs from the Pono Music online store, which is expected to charge much more than iTunes, Amazon, or other MP3 retailers. All the added expense could be a hard sell for those who’ve likely already paid for their favorite music multiple times over the years. Talking about Pono to Rolling Stone in 2012, My Morning Jacket front man Jim James also mused, “I’ve already bought Aretha Franklin’s ‘Respect’ a lot of times. Do I have to buy it again?”

Another Pono quirk: The player doesn’t allow listeners to adjust the treble or bass. The idea here is that the device is a delivery vessel for what the artists intended their music to sound like — hence, no futzing with the levels. “Equalizers are against the Pono ethos,” says Abrari. “The only thing you control is the volume. Neil wanted to make sure you hear what the artist recorded, as opposed to you or somebody in the process manipulating the sound.”

So is what Pono delivers worth the cost? Comparing the same songs on Pono with its counterparts on iTunes, Spotify, and vinyl, the superiority ranges from noticeable to stunning. On MP3, the guitar parts on Young’s “Heart of Gold” blare and blur. On Pono, they’re distinct, accentuated, allowing greater appreciation of their effect on the song’s overall arrangement. Similarly, the layered backing vocals and percussion on the Pono version of Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” sound lush and detailed. The presence of the Pono incarnation of the Rolling Stone’s “Brown Sugar” is such that you might be tempted to look around for Keith Richards while listening to it. In all cases, the music has the nuance and warmth, the human factor, that audiophiles crave, and that Young believes less obsessive consumers are also willing to pay for.

Pono’s online store is set to open sometime in December with around 2 million albums available for sale. And, as mentioned above, broader retail availability of the player is expected in early 2015. As Taylor Swift fans know, the future of the digital-music market is still widely in flux and deeply competitive. Even in addition to the ubiquitous iTunes and Spotify, there are already high-resolution streaming services such as Tidal, which charges $19.99 a month, and Deezer Elite. (Those last two services only offer 1411 kbps/16-bit FLAC files, while Pono is dealing in 9216 kbps/24-bit.) Abrari says Pono might someday support streaming services, as long as the quality meets the company’s standards.

For now, though, and for the foreseeable future, Pono has the unique advantage of being able to offer music fans the best digital approximation of master recordings. On that count, Pono justifies itself. But whether the device winds up as, to put it in distinctly Neil Young–ian terms, more of an After the Gold Rush–style game-changer or a Trans-esque noble curiosity remains to be seen — and heard.