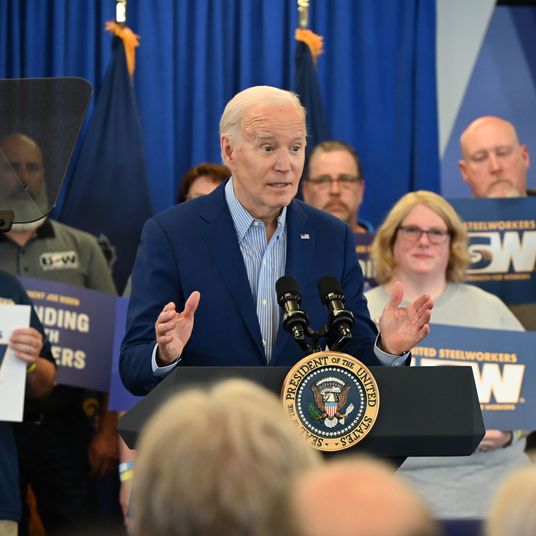

Back before a Staten Island grand jury declined to indict Officer Daniel Pantaleo for killing Eric Garner, before a Baltimore man named Ismaiiyl Brinsley assassinated officers Rafael Ramos and Wenjian Liu in Brooklyn as some deranged form of response, and before New York’s politics descended into chaos, with a crowd of hundreds of officers turning their backs on their mayor when he spoke at Ramos’s funeral and the head of the police union saying that de Blasio was acting less like the city’s responsible chief executive and more like the head of a “fucking revolution” — before all of this blazing December heat over the politics of crime, Mayor de Blasio gave a speech at a public housing project in Brooklyn addressing the city’s spectacular public safety record this year. In 2014, he noted, nearly all major crimes continued to decline and New York looks likely to see even fewer murders than it did last year, which set a record for the lowest total in modern history. These stats are particularly important to de Blasio politically, because he has promised that the less heavy-handed policing regime he envisioned (fewer stops, less harassment, more transparency and accountability) would not lead to more crime, and in this year’s crime data he could claim a little bit of proof. “We think it’s normal that we can bring crime down while bringing police and community closer together,” the mayor said, at the Ingersoll Houses in Fort Greene, on December 2. It was a striking speech, because de Blasio, adopting a technocratic tone, was arguing that crime had changed and therefore policing could change, too.

Before Ferguson, this could be seen as part of a broader political correction, in that the country in general had seemed to turn against the crime and punishment regime that has basically stood since the 1980s. Even most of the major Republican presidential candidates (Paul Ryan, Rand Paul, Rick Perry, and Chris Christie) have made it clear that they believed major reforms to reduce sentences and inmate population were overdue. States had been cutting prison populations to the extent that by 2013 the number of prisoners they housed was getting smaller rather than larger for the first time in 40 years. Scholars found that those states that cut their inmate population most dramatically had, unexpectedly, seen the largest drops in crime, which made it hard to argue that closing prisons would return us to the dark days of the ‘80s. When de Blasio built his campaign in part around the case against stop-and-frisk, and when Bill Bratton agreed to implement radical changes to the policy, they were taking a risk, in that any major increase in crime could be blamed on these decisions. But you could see their calculation: Politically speaking, they were riding a pretty strong wave.

But something strange has happened during the past month, both in the politics of New York and those of the country. In the debates over policing that followed the tragedies of Michael Brown and Eric Garner and Tamir Rice and officers Ramos and Liu, race has assumed the central role, displacing crime. This has brought about a more direct confrontation with our remaining national sickness around race, but it has also surfaced an atavistic, tribal strain in our politics, reminiscent of the racialized fights of an earlier era. It is probably no accident that some of the central figures of New York’s recent past returned to the public stage last week, and that their view diverged from de Blasio’s. Instead of a reasonable, technocratic decision to adjust policies of policing and punishment to a place where there is much less crime, they saw the debate as a declaration of allegiances — of whose side you were on.

“We’ve had four months of propaganda — starting with the president — that everyone should hate the police,” Rudy Giuliani said. “That’s what the protests were all about.” Ray Kelly suggested that de Blasio’s public statements that his son Dante, who is half-black, take “special care” when dealing with police “set off this latest firestorm.” George Pataki called the slayings of Ramos and Liu a “predictable outcome of divisive anti-cop rhetoric” from de Blasio and Eric Holder, Obama’s long-serving attorney general.

With all the talk of race, in New York and elsewhere, doubtless some of the police and their defenders feel as if they are being blamed for things that are not their fault, that a whole ugly national history is being dumped on their heads. On Fox News and CNN, Giuliani kept returning to his conviction that de Blasio was defaming the NYPD as racist. But in the responses to the assassination, it was possible to sense a deep perceptive chasm in addition to the emotional one — not merely over how the police should operate, but on what the nature of crime is. De Blasio called Brinsley a “heinous individual” and a “horrible assassin,” but his emphasis was always on the individual maniac, not anything he stood for or anyone he represented. There was surely some political calculation to this, alongside genuine belief, but it still differed noticeably from the police view. In the immediate aftermath of the attack, police sources told the Daily News that they were focused on the suspicion that Brinsley was “a member of the Black Guerrilla Family,” a large criminal gang with black nationalist politics, and that the slaying was a consequence of a concerted plot by the gang to “get back at cops for Eric Garner and Ferguson.” The story was quickly debunked — no one could find any connection between Brinsley and the BGF. But it seemed to reveal a basic difference in perspective — that crime is a function not of poverty but of individual pathologies and pathological networks, and that, without continued vigilance, it could still return.

Nearly every New Yorker now lives, in some meaningful way, in a post-peak-crime city marked by gentrification and safety, even in what were very recently very poor neighborhoods. The statistics that de Blasio rattled off at the Ingersoll Houses were astonishing: 80 percent reductions in murder and robberies since the early ‘90s. (Perhaps even more amazing is the statistic that the criminologist Frederick Zimring of the University of California-Berkeley likes to cite, that auto thefts have declined by 95 percent.) The mayor is, as my colleague Chris Smith astutely pointed out, lying low right now. But when he reemerges, one way to further de-escalate tension might be to continue in the cooler vein he displayed at Ingersoll: talk about the achievements of the NYPD in reducing crime; about the accomplishments of the last year as the department has scaled back stop-and-frisk while seeing continued declines in violence; about the false choice of the trade-off between security and freedom. He could talk, in other words, less about policing and more about crime, which has the added benefit of giving the police credit for accomplishments so sustained that they have enabled a new approach. The tide that national politicians of all ideologies sensed before Ferguson, of liberalizing attitudes toward punishment, still exists. The stats are all on de Blasio’s side.