Let’s first get rid of all pretenses of objectivity: I’ve been in the streets for 14 hours over the last two nights more as a protester than as a journalist. I marched because I believe that the dual failures to charge the police officer killers of Eric Garner and Michael Brown with a crime of negligent or unnecessary violence points to a systemic devaluing of black lives. But being in the mix of a protest isn’t nearly as uncomplicated as the beliefs that compelled me, and thousands of others, into the streets on Wednesday and Thursday night.

What’s it been like? Some stray observations:

There might not be an organization, but leaders emerge. Night one, they were young white kids who seemed well versed in protest language and very likely were Occupy veterans. I got out of work on Wednesday and headed straight to Rockefeller Center, where Twitter had told me that protesters were trying and failing to stop the tree lighting. The crowd was pressed against a barricade at 48th Street and Seventh Avenue, yelling at police officers to let them through, when one polite young man got them all to quiet down by raising his fist and yelling “Mic check!”’ which then echoed through the crowd. He then shouted out his message in short bits that the crowd would shout out again so others could hear: “There’s another group. Going to Columbus Circle. I think that we. Should keep marching. And keep the momentum going. And meet up with that other group. But only if that’s okay. With all of you.”

It took a couple of tries, but soon we were on our way to Columbus Circle on a zig-zagging route and then down Tenth Avenue, where we met another group and doubled our numbers. Everything on Night One was put to a decisive group vote, which was amazing given our numbers. At another mic check around the south side of Riverside park, we had a shout-discussion about whether to keep going or to exit, with leaders reasonably explaining that we’d made our point on the West Side and needed to go back to the streets where we’d be more visible.

Night Two was far more haphazard. The beginning, a massive gathering of thousands in Foley Square, had been far more planned and organized than Night One, but the course of your night seemed to be dictated by whichever group you wound up in. The one that crossed the Brooklyn Bridge with the Garner family and staged a die-in in front of the Barclays Center seemed to stay strong with thousands, while I wound up in a group that circled Tribeca multiple times before gathering at the Staten Island Ferry Terminal to regroup, then heading over to block the Holland Tunnel entrance and finally marching up the West Side Highway. Perhaps it was because the police were more effective, or because our de facto leadership was less strategic, but we kept running into road blocks that would force us onto sidewalks and split us into an ever-dwindling group. We had a lengthy mike check wherein two protesters got up on the hood of a car and one tried to get the crowd to make a decision on whether we were going – but the other interrupted him before we could decide by chanting “The people united / will never be defeated.” The leadership mode of Night Two seemed to be grandstanding without a plan. Multiple times, half the group would head North and the other half East, both with extreme purpose, and we’d have to regroup, all of which allowed the police to track us and close in, which they did, far more often than on Night One. The Occupy kids were sorely missed.

The best route always seems to be against traffic. It’s safer because you don’t have to watch your backs for cars, it’s more disruptive, and it means cop cars can’t follow you. The leaders on Night One seemed to know this. On Night Two, our group of several hundred kept getting split into smaller groups whenever we’d flow with traffic and cop cars would pull into gaps to cut off the rear.

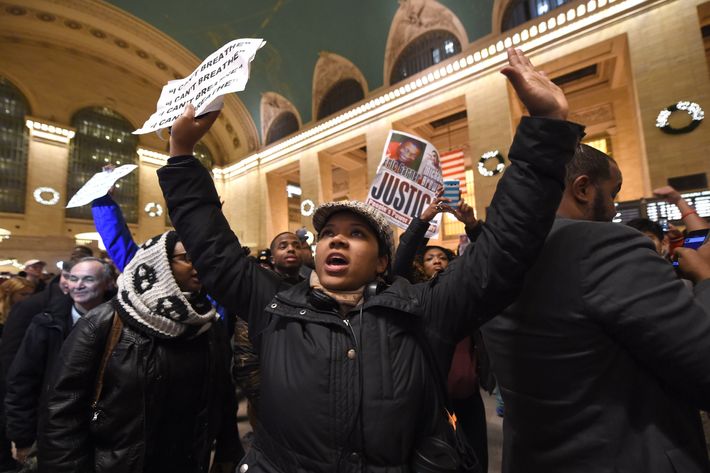

Chanting people have pretty bad rhythm. Many, many times we had multiple chants going at once, or the same chant, with several people always half a beat off. The perennials included: “I can’t breathe”; “NYPD / KKK, how many kids have you killed today”; “Hey hey, ho ho, these racist cops have got to go”; “How do you spell racist? NYPD”; “Hands up, don’t shoot”; “Whose streets? Our streets!” On Night Two, some new chants and slogans emerged: “My skin color is not a crime”; “Back up, back up / we want freedom, freedom / these racist-ass cops / we don’t need ‘em, need ‘em”; and “Grand jury? Bullshit!” Musicians were always a welcome addition for keeping time and spirits high. It really does help to bring some kind of noise-making device for when your voice goes. “You need to have a snare drum on you at all times these days,” said one woman walking beside me during a particularly quiet moment. “Never know when you’re gonna need it.” I’d say add comfy shoes to that list, and extra phone batteries.

Honking helps more than you think. On Night One on the West Side Highway, it seemed like every other car was honking in support, while stuck in traffic that the protesters had caused. And as the traffic jam went on even longer, everyone from a white woman to a cab driver in a turban was sitting at their wheels with their hands up. One guy stood in the door well of his truck with the door open, alternately banging on his horn, filming, and holding his hands up. On Night Two, it was a uniformed doorman, a young black man, standing outside a tony building in Soho with his hands up, who got me choked up.

There’s no greater energy boost than finding other protesters. One of my Twitter friends asked an NYPD officer where the protests were on Thursday night, and the officer replied, “Everywhere. Seriously, everywhere.” Which seemed to be true. Each night, whatever group I was with would unexpectedly run into another group that had also been marching in its own spontaneous pattern. The rush was always immense, particularly because it would increase our numbers after we’d been diminished by police blockades.

Things can turn volatile very quickly. On Night One, we marched onto the West Side Highway around 48th Street, taking over both sides of the West Side Highway before encountering a line of cops in riot helmets and carrying shields. “You killed Eric Garner!” protesters screamed in their faces. Every time it looked like the cops were going to break the line and let cars through, a swarm of protesters would start running over the median. One white officer brandishing a nightstick started shoving his way through the crowd, motioning for cars to move forward though to do so would have mean running people over. The cops jumped onto the median, it seemed to defend their ground, and began shoving protesters who tried to get up there with them. One protester who managed to breach the line was wrestled to the ground, his face pushed against a tree trunk and the dirt beside it. The entire situation was terrifying, until somehow we just all started moving uptown again.

When we exited the West Side Highway, we found ourselves on Broadway, which is where the first police nets came into play around 79th Street. Protesters scrambled back and forth over medians, and finally crowded onto sidewalks to avoid arrests, but the police officers were blocking those, too. Officers in riot gear stood next to Christmas tree stands outside of Zabar’s holding plastic zip-tie handcuffs at the ready. Multiple times, hundreds of people would break into a run that felt dangerously close to a stampede.

On Night Two, our group faced indiscriminate pepper spray and arrests on 14th and Eighth Avenue. A brigade formed with people running into a deli to get milk and offer it to those who needed it to soothe their burning eyes. Someone said that the police sprayed a child, one of the few, if any, still marching at 10 p.m. In midtown, we faced at least three more blockades with more arrests. The NYPD tactic each time seemed to be to split our groups by sending some people north and others south. At the end of Night Two, our group heading uptown on Ninth Avenue ran into a group heading west on 51st Street, which doubled our numbers. When we ran into a police blockade on 51st, the confrontation quickly grew violent, causing near-stampedes on the narrow roadway with nowhere to go. There were multiple arrests — bodies being slammed against the pavement and faces pressed into the chain-link fence of a construction zone — and one NYPD officer fainted and had to be carried away in a stretcher. One of my fellow protesters said he saw one of the arrestees being carted off with blood streaming down his face.

Protesters have an ugly side, too. Personally, I felt uncomfortable every time a protester would run up to an officer and scream “Pigs! Pigs!” in his face. Or slam on the hood of a police vehicle and flip off the cop at the wheel. I have friends who are NYPD officers, who I consider to be kind, non-racist people. They’ve told me stories of the death and inhumanity they witness daily — a horrific rape on Tuesday, a beautiful DOA on Friday, in which a 90-year-old Puerto Rican passed away in her sleep where she lived in the Bronx with her two sons. They speak of their jobs with a sense of duty and compassion for the ethnic communities they serve, as well as caution, because they know that what they may have to do in a volatile situation won’t always look good to outside viewers. When protesters would get in the faces of individual cops and yell, “You killed Eric Garner,” I’d imagine my friends having to endure that, and it was hard to watch. I also know that the next time I have a beer with my NYPD friends, I’ll be wondering about what lines they may have crossed on the force, whether they, too, are operating off of biases I can’t detect and that they may not even be aware of themselves.

For all the ups and downs, the transcendent moments make it worth it. On Night Two, that moment was when our group sat down at the mouth of the Lincoln Tunnel and, fists raised, held a moment of silence for Eric Garner and Michael Brown. On Night One, that moment came on the West Side Highway. Our group had been split in half, with everyone on the northbound line stuck behind police barricades while those of us on the southbound side marched forward. We staged a sit-in in front of a line of stopped cars, their headlights trained on us, then kept moving uptown through the cars, until as the road crested, there were none, on either side. Six lanes of traffic entirely cleared, with the Hudson glistening to our left. The only sounds were our chanting and a police helicopter close overhead. Then behind us, we heard a cheer and looked back to see a huge wall of people coming our way up the empty Northbound lane, carrying flags and massive banners. A man in a wheelchair who’d been on the Southbound side wanted to join them. Strangers helped lift him and his chair over the barrier so he could help lead the charge. He carried a sign reading, “To My Unborn Son / People will see the color of your skin / Before the content of your character / Don’t allow their perception of / the former dictate the latter.” It was one of the most powerful experiences of my life.