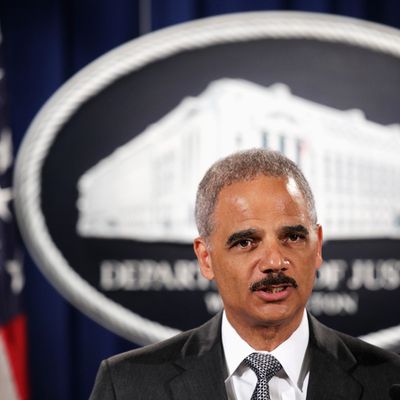

With protests still raging over recent police shootings of unarmed black men and boys, and over the legal system’s seeming paralysis in the face of police-prosecutor solidarity, the nation’s first African-American attorney general began a farewell tour that was also a last-gasp effort to start making things right. Last week the tour brought Eric Holder, who announced his decision to step down in September, to Memphis to host the second in a series of community dialogues he hoped would address, and perhaps even begin to assuage, the anger being directed at police in cities around the country.

On the first stop, in Atlanta, Holder spoke at historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was ordained and preached. In Memphis, he stood on the balcony where King died, at the National Civil Rights Museum, a modern facility grafted onto the remains of the Lorraine Motel, where the contents of rooms 306 and 307, used by King and his lieutenants in those final hours before the horror, are preserved behind Plexiglas walls.

At the museum, Holder held a closed-door roundtable with pastors and police, students and community leaders. Then we boarded a replica of the bus Rosa Parks rode into history, to talk about the things the attorney general has said and done and the things he feels the country has yet to do.

I’ll just start by asking you: Do you believe that African-American and Latino young people should fear the police?

I don’t think that they should fear the police. But I certainly think that we have to build up a better relationship between young people, people of color, and people in law enforcement. There’s distrust that exists on both sides. There’s misunderstanding that exists on both sides. And we have to come up with ways in which we bridge those gaps, so that people don’t demonize other people; so that people understand, on both sides, that there are people trying to just do the best that they can.

We’re not at a stage yet where I can honestly say that if you’re a person of color, you should not be concerned about any interaction that you have with the police — in the same way that I can’t say to a police officer, “You shouldn’t worry about what community you are being asked to operate in.”

Thinking back a decade and a half, I’m reminded of the words of a certain deputy attorney general concerning the case of Amadou Diallo, a young West African immigrant shot by police in the vestibule of his own apartment building. At the time, that deputy attorney general, Eric Holder, issued a memorandum explaining why there was not going to be a federal prosecution of the officers who were acquitted in that killing. You said there was a sense of mistrust between black communities and police that needed to be bridged. What does it say that we essentially are in the same place now, so many years later?

It means that we, as a nation, have failed. It’s as simple as that. We have failed. We have understood that these issues have existed long before even that 2001 memorandum by that then-young deputy attorney general. These are issues that we’ve been dealing with for generations.

And it’s why we have to seize this opportunity that we now have. We have a moment in time that we can, perhaps, come up with some meaningful change. It’s what I’m committed to doing, even in the limited time I have left as attorney general. And I’ll certainly continue to do it after I leave office.

It’s what this administration is committed to. But I also feel that the nation is really ready for this kind of change. And I would hope that, 10 years from now, 12 years from now, we will not look back on this as a lost opportunity.

I think, in particular, what happened in New York with the whole Garner matter — which I can’t really get into, because it’s something that we are still in the process of investigating — has galvanized the nation. And I think that we have to take advantage of this spirit, this feeling that exists now in our country, and make it better.

Is police training the issue? Or is it that police know they are so protected by the system that an individual officer who abuses his or her power can be confident that there won’t be any repercussions?

Well, certainly training is an important part of it. But we also have to look at the way in which police officers are judged. And if there is, in fact, a problem there, that is something that we need to address.

But again, I think that’s something that we need to look at really honestly. What are the statistics? What are the numbers of people who are involved in these kinds of shootings? Are there deficiencies that we are seeing? Are there patterns that are repeating themselves?

And one of the things we need to do is do a better job of just collecting statistics. We don’t necessarily have the basis now for looking at this country as a whole and understanding how big the problem is. It’s one of the things our Bureau of Justice Statistics is trying to come up with, a way in which we can start to gather this kind of information. And that’ll give us a much better way in which we can get a handle on this problem.

You came into office and, very early on in your tenure, you made a very strong statement that we’re a nation of cowards in dealing with the issues of race. Do you still believe that?

Well, as a nation, we are too reluctant to talk about racial things. It’s something that’s painful. It’s difficult, given the history of this nation. And the easier thing to do is to try to figure out a way in which you just kind of deal with the issue that’s before you and then really not deal with the underlying concerns.

So yeah, we’ve not done all that we can. I’m hopeful that, at this time, with this president, that we can make progress in ways that we have not in the past.

You were a surrogate for then-candidate Barack Obama in 2008. And there was a lot of hope that perhaps if he became president, he would be able to galvanize that very conversation. Do you feel that any opportunities have been missed?

No, I don’t think so. If you look at the work of the Justice Department over the last six years, we’ve done a whole variety of things, including bringing cases against police departments that have acted in unconstitutional ways. I think that I’ve been really out there talking about things [that are] racial and gotten a lot of criticism for it. But you know, that’s fine.

Raising these issues, coming up with substantive programs, I think we’re in a better place than we were before. Maybe not as far as people expected with the election of the first African-American president or the selection of the first African-American attorney general. But even though we’ve made progress, and I’m proud of the progress that we made, there’s still much more that we have to do.

Your critics on the right might say, “Well, this guy came out swinging. He came out saying, ‘We’re a nation of cowards on race.’ And so it’s not surprising that the other side swung back.” Do you feel, in any sense, that you might have polarized the debate when it comes to talking about race?

No. You see, I think that people have to be prepared to deal with the truth, with the facts — and not be defensive about that. I mean, if people look at the entirety of that speech, I talk about the fact that people have to be in a position to feel safe to express opinions. The other side has got to be able to hear in a way that you’re not necessarily being critical, but to take it in — in a thoughtful way. This is a painful process to go through. This is a nation, after all, that had to deal with slavery and then legalized segregation.

And so we still have a lot that we have to get through. We’re still suffering the impacts of a racial system that was inconsistent with our founding documents. And so race is still a hard, hard thing for people to talk about and to deal with.

White president, white attorney general: Would there have been this tough, difficult relationship with Congress?

Hard to say. I mean, the attorney general seems to be, lately, the person, whether you are white, black, Republican, Democrat, who catches a lot of grief. So there’s that — that’s just a part of the position.

I can’t look into the hearts and minds of people who have been, perhaps, my harshest critics. I think a large part of the criticism is political in nature. Whether there is a racial component or not, I don’t know.

I’ve tried to work my way through that and focus on what I can do, with the power that I have as attorney general, to make this country better and to deal with those racial issues that I talked about in that speech back in 2009.

You’ve been very critical of the way that you’ve been treated by Congress, on everything from “fast and furious” and all of these investigations. You’ve even heard threats that they’d like to see you impeached. Do you feel you’ve been especially disrespected as attorney general?

Unfortunately, I think that’s part of Washington in 2014. I would hope that my successor would not have to endure some of the things that I did. And I say “endure” only because I think I’ve shown respect where, perhaps, I haven’t been given any.

There are times when I wanted to just snap back. And there are occasions when I have. But there have been, frequently, more times when I’ve wanted to be a lot more aggressive in the responses that I’ve made.

Have I been treated well? You know, it doesn’t really matter. At the end of the day, people are not going to remember some of the silly stuff that was thrown at me. What they’re gonna focus on, I think, are the accomplishments that the men and women of the Justice Department have made under my leadership over the last six years.

What is the thing that you’ll look back on and say, “Really glad I did that”?

I think that speech I gave in August of 2013 to the American Bar Association, where we announced the Smart on Crime initiative and said, “You know what? We have to really rethink this whole way in which we are dealing with the war on drugs, in particular, and this whole question of mass incarceration.”

Who are we putting in jail? Who are we charging? What kinds of charges are we bringing? Are there ways in which we can incarcerate fewer people for less time and keep the country safer by coming up with evidence-based, scientifically proven alternatives?

And the thing you wish you’d done?

I think more about what we have done, the things we have accomplished. And I’m proud of the men and women of the Justice Department. I sometimes think I wish I had more time, even though I think it’s time for me to transition to something else.

There’s always something that’s just over the horizon or that’s just right out of grasp that you think that you’d like to spend more time on. Dealing right now, for instance, with this whole question of building trust between communities of color and people in law enforcement — this is something that I’d really like to spend a lot of time on. But unfortunately, my time is going to be short.

Do you think it’s time for us to end this declared war on drugs?

Well, I think we certainly need to ask ourselves questions about our drug-enforcement efforts. Are we focusing the limited resources that we have in the appropriate places? Are we bringing the appropriate charges? Are we putting people in jail for the appropriate lengths of time?

You know, the sale of drugs has ravaged certain communities. I’m concerned, however, that some of our law-enforcement efforts, though well intentioned, have had a destabilizing influence in those same communities. And so we need to step back and ask ourselves some really fundamental questions about the approaches that we have used in drug enforcement over the last 30 or 40 years.

So let’s talk about voting rights. In the wake of the Shelby v. Holder decision, should people be concerned?

Well, I think people certainly ought to be concerned. The Shelby decision, unfortunately, gutted the crown jewel of the civil-rights movement: the 1965 Voting Rights Act. I know that my successor, Loretta Lynch, will be hard on that issue in the same way that I have tried to be.

And I think all Americans can really unite around this issue. This is an issue that Congress, on a bipartisan basis, can and should address and deal with the concerns that were raised by the court and come up with a new Voting Rights Act.

What does it say that the excuse used to start gutting voting rights and to pass things like voter I.D. was the election of the first African-American president?

This whole question of voter I.D. laws is something that I find extremely disturbing, especially when you look at the studies that have shown that the instances of voter fraud do not justify these new laws and when you look at the impact of these laws — which is to make it more difficult for American citizens to vote.

That’s the thing that makes this country unique, makes us as great as we are: the ability for citizens to influence the way in which they are governed. And for people to turn their backs on that for political reasons is something that I find extremely, extremely disturbing.

And do you believe in your gut, having been in Washington now for the last six years, that Congress will address the Voting Rights Act?

Well, it is my hope that they will. You know, we’ve got people like Jim Sensenbrenner, a Republican, who has, I think, very courageously led this effort. But this is a gut check. This is a gut check for the Republican Party. Where do you stand? Are you gonna be true to the values and the history of a great party? Or are you gonna do something that, in the short term, is politically expedient but that, ultimately, you will find historically shameful?

We’re standing here in the National Civil Rights Museum. Do people appreciate enough what was accomplished by the civil-rights movement? Have people forgotten the lessons of it?

We are surrounded here by some very stark reminders of how different our nation was. And I think people tend to forget all that we had to go through to get to the place where we are now, a nation that has made substantial progress. But people sacrificed, people died, so that I could be an African-American and be attorney general of the United States.

We as Americans tend to have short memories. And I think this is a place where every American probably ought to spend some time to understand how deep the problems were, how courageous the people were in dealing with those issues. There’s a lot that we can learn here that I think would be very useful in the in the 21st century.

And yet, young people seem to remember it. Because they’re out in the streets right now, 100-plus days of protests. What do you think when you see those young people out there, sleeping out, doing die-ins, and really just galvanizing their own movement?

That’s the essence of who we are as Americans. We protest. We get loud. We disrupt things — all with the hope that we’re gonna make the country better. They have raised issues that we need to discuss.

This is an opportunity for this nation to listen to those young people. And some of ‘em aren’t so young. It’s a multiracial effort that I see. This nation needs to deal with the concerns that they have raised and make this nation simply better.

That’s all we’re asking for — just make the nation better.