Several masked gunmen entered the offices of Charlie Hebdo, a French satirical magazine, and opened fire on the writers before speeding away in a waiting vehicle. Twelve people have been confirmed dead — including two police officers — in the Wednesday-morning attack, and the gunmen, along with a driver, are at large.

The attackers were armed with automatic weapons when they stormed the office, forcing many other building occupants to seek refuge on the roof. A getaway car — which the attackers later swapped out by hijacking another vehicle — was waiting for them outside. A video of the scene shows the assailants walking over to an injured person, apparently a police officer, on the sidewalk across from the office in order to kill him before speeding away.

Wednesday’s attackers cried, “Allahu Akbar,” or “God is greatest,” in the course of the shootings, and “We have avenged the prophet,” on their way out of the building. This wasn’t Charlie Hebdo’s first brush with extremist threats, either — it had already been firebombed in 2011. In an address at the scene of the shooting, French president François Hollande said that the magazine had been subjected to threats before, leading to heightened security at the publication. He called this morning’s events “a terrorist attack.” In a follow-up address Wednesday evening, Hollande promised that “liberty will always be stronger than barbarism.”

“We will win because we have all the capacity to believe in our destiny,” he said. “Vive la république. Vive la France.”

French designer Corinne Rey, an eyewitness to the attack who was with her young daughter when the gunmen made her let them in, said the attackers “spoke French perfectly” and claimed to be affiliated with Al Qaeda.

That the attackers sped away instead of fighting to the death, however, means that Wednesday’s attack is different in style from the suicide attacks often deployed by terror organizations. Mia Bloom, a professor of security studies at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, tells Daily Intelligencer that the highly-trained gunmen may have been too valuable to waste on such a mission — especially given that a suicide attack would have only required one bomber. “This is a far more dangerous kind of attacker because the terrorist group invests heavily in their training and preparation, and will be able to have a second or even a third strike if they want to really spread terror and panic beyond the magazine and the 11th arrondissement,” she said, referring to the area of Paris where the attack occurred.

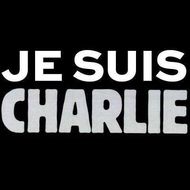

The popular Charlie Hebdo is known for publishing provocative cartoons, including ones attacking Islam, politicians, and other public figures. It was founded in 1969 by the staff of Hara-Kiri, a magazine banned for “a front page appearing to mock the death of French President Charles de Gaulle.” In a similarly controversial fashion, this week’s cover features a just-released book by polarizing writer Michel Houellebecq, in which an Islamist president wins in France and bans women from the workforce. After the attack, the magazine’s website was updated to show only one image, reading “I am Charlie” in French.

Some reports now say the attack happened during an editorial meeting. Among the dead is Stephane Charbonnier, a journalist known as “Charb,” and one of the heads of the publication. He had recently published a cartoon taunting extremists:

In 2012, he defended the right of those offended to protest the magazine. “Why should they prohibit these people from expressing themselves?” Charb said. “We have the right to express ourselves, they have the right to express themselves, too.” And in 2013, Inspire Magazine, an English-language Al Qaeda publication that was run by American citizens Samir Khan and Anwar al-Awlaki before they were killed by drone strikes, named Charb as one of its “most wanted”:

Also dead are cartoonists Jean Cabut (a.k.a. “Cabu”), Georges Wolinski, and Bernard Velhac (a.k.a. Tignous), as well as economist and journalist Bernard Maris. Editor-in-chief Gerard Biard was in London at the time of the attack.

Wolinski’s daughter shared an image of his workspace on Instagram:

“No barbaric act can ever extinguish the freedom of the press,” Hollande said in a statement. “We are a united country that will come together to help each other.” In Paris, the hashtags #CharlieHebdo and #JeSuisCharlie were trending Wednesday morning.

David Pope, cartoonist in Canberra, Australia, memorialized his fallen colleagues with a drawing:

French cartoonist Tommy Dessine also drew one honoring the cartoonists, with God saying, “Oh no … not them … ”

The staff at Agence France-Presse took a group photo in support:

And an old New Yorker cartoon became relevant again:

Many international leaders have reached out with messages of support for France. President Obama condemned the “horrific shooting” in a statement. “France is America’s oldest ally, and has stood shoulder to shoulder with the United States in the fight against terrorists who threaten our shared security and the world,” he said. “France, and the great city of Paris where this outrageous attack took place, offer the world a timeless example that will endure well beyond the hateful vision of these killers.”

Another condemnation of the attack came from Tariq Ramadan, a Swiss Muslim intellectual who is also the grandson of Hassan al-Banna, the founder of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood. “Contrary to what was apparently said by the killers in the bombing of Charlie Hebdo’s headquarters, it is not the Prophet who was avenged, it is our religion, our values and Islamic principles that have been betrayed and tainted,” he wrote in a Facebook post. “My condemnation is absolute and my anger is profound (healthy and a thousand times justified) against this horror!!!”

The attack calls to mind similar incidents in Denmark and the Netherlands. In 2004, Dutch film director Theo van Gogh was killed by a Dutch-Moroccan man for a film criticizing the status of women in Islam, which he co-created with Somali-born activist Ayaan Hirsi Ali. A planned attack in 2010 against Jyllands-Posten, a Danish newspaper that had published cartoons of the prophet Muhammad, was foiled.

Images of the Prophet Muhammad are particularly controversial in Islam. Many branches of the religion interpret certain hadith, or teachings of the prophet, to prohibit visual depictions in an effort to eliminate idolatry.

Charlie Hebdo notably published cartoons of the prophet in 2012, in the midst of outcry over the controversial film The Innocence of Muslims. A day after publication, the French government closed embassies, schools, and other outposts in 20 countries out of fear of attacks. In 2006, it reprinted Danish cartoons of the prophet. And the last cartoon tweeted by the paper ahead of the shooting featured ISIS leader Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi:

France has also been the subject of threats from the terrorist group. In September, the ISIS-affiliated Algerian terrorist group Caliphate Soliders beheaded Herve Gourdel, a French tourist, after the country refused to halt air strikes on the Islamic State.

This post has been updated throughout.