The Rise and Rise and Rise of ABC’s Ben Sherwood

His meandering, joyous — or maybe seriously Machiavellian — path to the top.<br /><br />

to Succeed

in

Television

rise of ABC’s Ben Sherwood.

One stormy evening this past May, Manhattan’s television-news aristocracy filed into the Pool Room of The Four Seasons to bid adieu to ABC’s Barbara Walters, who was retiring after five decades on the air. Anderson and Katie were there, Savannah and Al. Diane Sawyer and Brian Williams turned down the same trays of canapés. As much as this was a farewell to Walters, it was also the first public opportunity for kissing the ring of ABC’s brand-new TV overlord, Ben Sherwood, who two months before had been promoted from leading ABC News to the presidency of the Disney/ABC Television Group, a job that would put him in charge of the entire broadcast network and the dozens of other television properties Disney owns wholly or in part, like the various Disney Channels and A&E, a multibillion-dollar, highly profitable business. The promotion made him about as powerful as television executives get, with only one man to report to, Disney CEO Bob Iger.

Walters had worked for Sherwood’s predecessors as heads of the news division, David Westin and Roone Arledge, for decades, but she offered perfunctory thanks to that pair from the stage. Instead, she found and locked eyes with the executive who’d led the division for just over three years. “I want to say special words to Ben Sherwood,” Walters said, motioning to him. “Ben, you made us all believe we could win. And with your vision, your leadership, and your passion, we have.” Everybody there cheered for Sherwood, gangly and blue-eyed with a prominent dimple in his chin. Iger certainly cheered, as did Anne Sweeney, the woman who would be stepping aside for Sherwood after ten years in the job. So did Sawyer, who would announce she was leaving World News late the following month, willingly, everyone involved swears, despite rampant outside speculation that Sherwood had forced his onetime mentor to relinquish the chair before she was ready. Also applauding were The View stars Sherri Shepherd and Jenny McCarthy, unaware they would be let go the day following the Sawyer announcement, after the show was overtaken in key demographics by CBS’s The Talk.

For the 50-year-old Sherwood, Walters’s tribute was a touching moment—a “grace note,” he might call it, if he were producing a news segment about his own breakneck corporate ascension—in his singular, controversial, herky-jerky career in (and often out of) TV. When talking about his path, Sherwood, a proud polymath who quit the TV business no fewer than three separate times to do things like move out to California and write novels, likes to quote a Kenneth Rexroth translation of a Japanese koan about the meandering nature of fate: “I’ve always known that I would take this road, but yesterday I did not know that it would be today.” Many at ABC News praise Sherwood as perhaps the most engaged, inspiring, empathic leader that the television industry has ever produced. “The best boss I’ve ever had,” declares Nightline and GMA weekend-edition co-anchor Dan Harris, who says Sherwood’s management style is best described using the Buddhist term mudita, which, roughly translated, means “sympathetic joy” and is often cited as the emotion opposite to Schadenfreude. A purely Zen gloss on his rise, however, misses how thoroughly intentional Sherwood has been all along the way. “Anybody who gets to that position and has the kind of success Ben has doesn’t do it through happenstance,” says Andrew Morse, a veteran ABC producer and Sherwood admirer who is now one of Jeff Zucker’s deputies at CNN. “You have a plan, and you plot your moves.”

Last March, Iger announced that in February 2015, Sherwood would succeed Sweeney, who had climbed into the Disney job after years of toiling in lesser gigs at Nickelodeon and FX. The extraordinarily long transition, with Sherwood working alongside Sweeney for nearly a year, was perhaps occasioned by his greenness: Prior to becoming ABC News president, his professional experience heading anything consisted of two and a half years as executive producer of Good Morning America, a period that hardly anticipated his rise. And although as president he accomplished what had previously seemed impossible at ABC—a top-rated morning show and a No. 1 evening-news broadcast—the new job will be a substantial leap. Sherwood has told associates that before he was considered for the job, he was ignorant of even the rudiments of the pilot process. Next month, he’ll be presiding over 24,000 annual hours of original programming.

The Sherwood kids, Ben and Liz of Beverly Hills, were the first American brother-and-sister pair to each win the Rhodes scholarship. Before their dual triumph (in 1981 for Liz, who is now the deputy secretary of the Department of Energy, and in ’86 for Ben), they grew up rich, the children of a prominent attorney and a board-sitting stay-at-home mother. Both parents seemed to view their home as a laboratory for breeding hyperachievers. Young Ben carried around a worn-to-pieces copy of the Guinness World Records book in a shoe box and once confessed to an interviewer that he’d been particularly fascinated by the gluttony section. (In the late ’90s, while researching a novel set in the world of the Guinness book, he attempted to break the egg-tossing record on Central Park’s Great Lawn. He would bring his interest in world records to Good Morning America coverage.) A 1986 Los Angeles Times article about the siblings noted Ben’s diverse achievements—working for a U.N. relief agency on the Thai-Cambodian border; proficiency in French, Chinese, and Russian; internships at the paper and CBS News; as well as wackier pursuits like mime and magic, and winning a disco-dancing contest with his grandmother. Ben was quoted as saying “Machiavelli, who is widely misunderstood, said that in the long run it’s not that important to be popular because popularity is fleeting but respect is permanent.”

Then, in 1988, Andrew Sullivan wrote the article that has dogged and defined Sherwood for more than 25 years. Sullivan, who was then studying at Harvard, had written a feature for Spy called “All Rhodes Lead Nowhere in Particular.” Rhodes recipients, he wrote, were “the apotheosis of the hustling apple-polisher, the triumph of the résumé-obsessed goody-goody, the epitome of the blue-chip nincompoop.” According to Sullivan, after reading a draft of the piece, Spy editors thought that Sherwood, with his particular combination of earnestness and unvarnished but apparently directionless ambition, merited a long sidebar of his own. Thus was born “Résumé Mucho,” in which Sullivan labeled him “the ultimate in a long line of centerless résumé featherers” and quoted unnamed Harvard classmates testifying to his unpopularity. Sullivan even found one classmate to go on record. “Ben is one of the most hated people alive,” Clark Freshman told him.

The accuracy of the Sherwood portrayed in “Résumé Mucho” has long been disputed. “My quote was taken out of context,” Freshman tells me. “Even of our little crowd, Ben wasn’t the most hated person, let alone one of the most hated people of his generation.” Friends will allow that Sherwood was ultracompetitive, and, as his friend the author Bruce Feiler wrote, the champion Harvard debater appeared “uncomfortable in social situations unless there was a prescribed set of rules.” He wasn’t athletic, was big into trivia, had probably never tried pot, guesses a friend from then. He was odd, certainly, and uncool, probably—but not a raging asshole.

But every time Sherwood got a new job, the Spy piece would invariably appear, usually in the form of much-passed-around, dog-eared photocopies—that is, until Sullivan retyped it and posted it on Atlantic.com in 2010 within hours of Sherwood’s being named president of ABC News. Friends say that Sherwood was deeply wounded by the piece and remains sensitive about it.

The year after the Spy piece immortalized him, Sherwood joined ABC as an associate producer for PrimeTime Live. In August 1992, he traveled to Sarajevo with Sam Donaldson and producer David Kaplan. As Kaplan and Sherwood rode shoulder to shoulder in a van through a stretch of bombed-out buildings, there was a loud metallic pop. Kaplan, a hard-boiled type who’d decided to forgo wearing his bulletproof vest, had been shot, and he later died on the operating table. That night, a Kaplan tribute was put together for PrimeTime, with Sherwood now acting in the senior-producer role. “We were both emotional,” Donaldson says. “When I was not writing and Ben was laying in picture, I would cry a little bit and I’d collect myself, then I’d write a bit more, and Ben would cry a little bit.” He remained traumatized back in New York.

A harrowing period got even rougher when, eight months later, Sherwood’s 64-year-old father died following a cerebral hemorrhage. Sherwood quit ABC and moved back into his old room in his parents’ house. He’d stay in Los Angeles for the next four years. “I thought I was coming out to take care of my mother,” Sherwood will often tell friends. “I did not actually realize I was coming out to take care of me.” (Sherwood, citing his still-transitional role at Disney/ABC, declined to participate in this article.)

During the years Sherwood spent in L.A., he worked on Kathleen Brown’s 1994 failed bid to become California governor, on the basis of which he was signed to write a book about the country's shifting political and racial demographics. But after burning through a copy of Michael Crichton’s The Andromeda Strain he’d found in a seat-back pocket on a flight, Sherwood decided instead he’d write a techno-thriller about a secret agent racing against time to find stolen plutonium. “He wanted to come out of nowhere and be a best-selling author,” says Joni Evans, then of William Morris, who first learned that she wouldn’t be getting the political book when Sherwood dropped off a completed manuscript for Red Mercury. “It was amateurish.” She suggested he use a pseudonym—“Max Barclay”—that might protect his future as an author. After Red Mercury failed to make him Crichton, Sherwood would set to work on The Man Who Ate the 747, a comic novel featuring as protagonist the judge of a Guinness-like record book. He began shopping a screenplay before Evans had a chance to sell the book. By the time of his publication, which failed to make a splash, he was back in television.

Sherwood spent more than four years in New York at Nightly News and rose to become second-in-command. But at the beginning of 2002, he again ditched the news business. After 9/11, he told colleagues, his outlook and priorities had fundamentally changed, and he’d fallen in love with a film producer, Karen Kehela, who is now his wife. Others offered a less philosophical reason for Sherwood’s departure. “He didn’t stay because he didn’t get the No. 1 job at Nightly News,” Tom Brokaw told the New York Times in 2011.

Sherwood attacked novel-writing with a renewed ambition for a couple of years. He penned the unapologetically sentimental, supernaturally themed Death and Life of Charlie St. Cloud (which was eventually made into a Zac Efron vehicle). But just a month after the book’s publication date, many at ABC News were stunned when Sherwood was named executive producer of Good Morning America. The announcement sent the show’s staff online to find out more about their mysterious new boss. At bensherwood.com, his author website, they found a self-administered Q&A. “Why do you think each of your books has been sold to the movies?” Sherwood inquired of himself.

When Sherwood stepped in, GMA had been beaten by Today for so long that the show had briefly been on the chopping block. Its fortunes started to shift with a team that included Sawyer and Charlie Gibson and veteran ABC producer Shelley Ross. Ross drove the staff hard. “Sleep is for sissies” was a favorite credo, making her unpopular with many and with Gibson in particular. (Anchors had the power to hire and fire the producers they ostensibly reported to.) Ross was asked to leave and later claimed she was fired specifically to make way for Sherwood, who had been heavily politicking for her job from outside the building by filling the anchors’ heads with the notion that only he possessed some secret recipe for finally defeating Today. She wrote on her personal blog that, while ostensibly retired from the TV news business, Sherwood was “secretly e-mailing the anchors, the management, and anyone who would listen. He convinced Diane Sawyer, for one, that he was a secret consultant for Today.” (“Contrary to myth,” Sawyer tells me, Ross’s ouster “wasn’t my decision.”) But David Westin acknowledges Sherwood was handpicked by GMA’s stars. “After consulting with some of the people most directly involved in the program (especially Diane and Charlie), I concluded that Ben was the right person to build on the foundation we’d laid,” he wrote in an email.

Sherwood ran GMA for two and a half years. He had some early ratings successes by making the stars of then-red-hot Desperate Housewives nearly permanent set fixtures. But by the time he left, in September 2006, his show still hadn't caught up to Today. Sherwood defenders say the producer wasn’t allowed to make the changes required for victory. Gibson wasn’t a morning person, treasured his hard-news bona fides, and would consequently have to be dragged kicking and screaming to do the kind of lighter fare it takes to win. Sawyer, ultimately, did only what she wanted to do.

In June 2006, Sherwood informed the staff that his priorities had changed once again. He would be heading back to Los Angeles to be closer to his mother, who was having complications in her treatment for ovarian cancer. Within ABC, many are convinced his departure was a Sawyer call. “I can’t confirm that Diane got rid of Ben,” says former 20/20 co-anchor Chris Cuomo, who has worked for CNN since 2013. “I was not privy to the process of his expulsion. But did I hear it? Well, I’ve worked at CNBC, MSNBC, Fox, ABC, and now CNN, and I have never worked at a place that was as gossipy as that place. It’s toxically gossipy, so what I’ve heard versus what I believe are two very different things.”

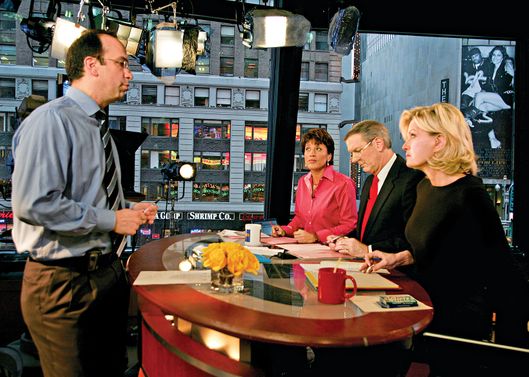

Just four years later, Sherwood, fresh off the red-eye from L.A., stood at a podium in the middle of an ABC News studio, flanked by Sweeney and Westin and the ABC News rank and file, having just been named the new president of ABC News. Once again, Sherwood had managed to get, from his time in the wilderness, a more professionally advantageous result than he would have by sticking around to slowly climb the ladder. Sherwood, Sweeney’s official announcement noted, a hair misleadingly, had “guided GMA to its two most successful seasons in history.” “I thought and continue to think this is the greatest building in all of television,” Sherwood said, visibly tearing up. The people he addressed—a few of whom had themselves interviewed with Sweeney for the position—again were dumbfounded at how Sherwood had managed to get the job. Initially there was trepidation. The division had been hobbled and demoralized by massive 2010 layoffs in which a quarter of the ABC News staff was let go. Upon the announcement, an anonymous video was posted that rehashed the Spy stuff and highlighted his inability to take GMA to No. 1, dubbing him “the Draco Malfoy of broadcast news.” It didn’t help the perception at all that while an ABC “network insider” commented that “Ben laughed it off,” Gawker reported that he’d initiated an internal forensic investigation on ABC News computers to ferret out whether the video had originated from within the division.

Only the year before, he’d released The Survivors Club, a nonfiction book on an issue close to his heart—why some people survive catastrophes like the Holocaust, plane crashes, or, in his case, a sniper’s assassination attempt, and others don’t. Out of a small office on Wilshire, with a couple hundred-thousand dollars raised from friends and family, he’d started an accompanying website that featured are-you-a-survivor assessment quizzes that he’d hoped, he told friends, only half-jokingly, could become “the next Facebook.” But his ABC-brass-emailing habit continued, with compliments and gentle critiques to GMA’s new host, George Stephanopoulos, who calls the notes he received welcome communications from “an interested observer, friend, fan.” He stayed in touch with Sawyer too. “He couldn’t resist writing me notes from the peanut gallery, starting with ‘What if you did this’ or ‘Maybe you could …’ ” she says. When Westin announced his retirement, Sawyer and Sherwood met for breakfast in Los Angeles; afterward, Sawyer told Sweeney she should meet with Sherwood just to hear his ideas. Sweeney was impressed, but Sherwood made it clear that he wasn’t interested in the job. Until three months later, when he called Sweeney back and said he’d changed his mind.

In his new role, Sherwood made dramatic changes at ABC. He systematically tore down the notion that any shows would act as fiefdoms led by possessive anchors. “Next show up” was the new rule—if there was breaking news, like the Boston Marathon bombing, everyone in the building, regardless of what staff they belonged to, would be required to help on pieces for whatever was airing next. Sherwood moved his own office from an executive floor down to be among segment producers. He also made a display of encouraging the staff: He announced everyone’s birthday personally (a practice he now continues, on Twitter, for the whole company). Underlings were encouraged to participate; “Best idea wins” became a mantra. Sherwood was always talking about winning “the championship.” If only ABC News, he’d say, could embrace his three pillars of “unity,” “creativity,” and “reach,” the championship could be theirs. Sporty aphorisms like “Play your game” and “Stay in your lane” would often be included as acronym sign-offs in emails—“PYG, Ben.”

Sherwood brought all the tricks he’d learned from his detours into fictional storytelling to shape the way ABC delivered news, advising his staff on one morning call that the story of a terrorist threat predicted for the tenth anniversary of 9/11 should be treated as a “thriller unfolding against a ticking clock which is September 11.” He had a taste for what he called “accessible” stories. The slow drip of incremental “today in Afghanistan” foreign-war staples of evening news fell by the wayside in favor of human-interest stories with perhaps less geopolitical import, like the hunt for African warlord Joseph Kony and Boko Haram’s kidnapping of Nigerian schoolgirls. “The thing that Ben is brilliant at is knowing how to make TV magic,” says ABC News foreign editor Jon Williams. “He once told me he’s a showman.”

Not everyone found Sherwood’s canny populism quite as appealing. The Tyndall Report, a site that monitors weekday nightly newscasts, declared that World News had become “certifiably Disneyfied,” and some retired old-timers, like Ted Koppel, whose prized hard-news show Nightline was now covering the war between “breastaurants,” are said to be particularly disheartened by the current state of ABC News. (Koppel, when asked about his media diet in 2013, conspicuously neglected to mention ABC News.) But even veterans who left in a huff over news standards will admit that ABC News had become a vastly more energized workplace than the one Sherwood inherited.

The legend of Sherwood as empathy machine also manifested around this time. He’d send baby gifts to colleagues he hadn’t worked with in years, visit a friend dying of cancer every week, fly out repeatedly to Los Angeles to help a producer work through her grief after her parents’ murder. Sherwood was a big hugger and cried often. After watching Chris Cuomo grill a California sheriff about why his deputies had so bungled the Jaycee Dugard kidnapping case, Sherwood told Cuomo, “This is why we do this, brother,” tears streaming down his face. “He cries about emotional stories,” says Tom Cibrowski, a former executive producer of Good Morning America, specifically citing Sherwood’s annual reaction to the “Emeril’s Mother’s Day Breakfast in Bed” series, in which, following a heartrending backstory, the chef surprises a contest-winning mom at her home. He takes things harder, more personally. “He’s a very emotional person,” says Cibrowski. “He carries things with him, he carries battles, defeats, and victories.”

For the first time in anyone’s memory, it became apparent that the news president had watched virtually every moment that appeared on-air, and had specific critiques, sent out at all hours. The control room would often get calls from Sherwood to change news chyrons in real time. Cuomo characterizes his leadership as “part cheerleader, part mentor, and part savant.” Junior producers would pick up their cell phones and be shocked to hear Sherwood offering congratulations and thanks. “You could say it’s all calculated, or you could say it’s really thoughtful,” says a senior producer who worked for him at ABC. “I feel like I know the guy pretty well, but it remains a great mystery to me. Maybe it’s somewhere in between.”

But Sherwood’s criticisms—especially in the first year of his tenure—could be withering, as when Harris received an email from Sherwood pronouncing the writing on a story he’d done for World News “flat and unimaginative.” Some in the division who received such notes didn’t always bounce back, and more than a few left, feeling no longer welcome. “Deselecting” was the term Sherwood would use for those who couldn’t hack it and bailed.

Sherwood scored outside the building as a rainmaker. He was able to forge an official relationship with Yahoo, a deal that immediately blew abcnews.com’s traffic way ahead of its network competitors. Sherwood also struck a deal with Univision, which had been courted unsuccessfully for partnerships by CBS, Fox, and Time Warner, to create Fusion, an English-language cable station devoted to young Hispanics and millennials. And, in what was his crowning achievement, on August 2, 2012, Sherwood sent out an email reading “TOTAL VICTORY!!”: After 900 straight weeks of being second best, GMA had finally beaten Today in both total viewers and in the important 25–54 demographic.

There had been substantial alterations to the show under Sherwood. He called what he did three-dimensional chess, sitting in the GMA control room, furiously graphing out on paper what all three morning shows were running. Weather stories often trumped political or foreign ones; the age-old morning-show fixture of talking-head politician spinning the Washington development of the day was 86’d in favor of salacious crime stories. The entire show was quicker, peppier; the sheer number of stories per hour increased markedly under Sherwood.

Still, in order to win the morning, Sherwood was convinced that using the press to pummel the competition—especially Matt Lauer, the perceived heavy in the ouster of Ann Curry—was nearly as important to ABC’s path to the championship as anything it was putting on its own airwaves. In the summer of 2012, according to a high-ranking ABC employee present in a postshow meeting in the GMA production office, Sherwood stood in front of the entire staff and told them what to expect as the battle heated up. “NBC will be coming at us in the press with everything they have,” Sherwood announced. “But don’t worry. We are masters of the dark arts.”

Some within ABC began to wonder if the dark arts were strictly a tool to be used against the competition. One particularly bruising period, toward the end of Sherwood’s time in the job, illustrated for many within the building a growing suspicion that Sherwood took the loss of talent on a personal, emotional level. In what one former ABC higher-up refers to as “management at its worst, just ineptitude,” the contracts of all five of the GMA principals were written to come up within the same year. (Three of these Sherwood inherited.) Though Robin Roberts’s contract was technically up later in the year, the GMA ensemble watched news leak to “Page Six” that ABC had negotiated her contract first, signing her for more than $13 million a year. That extraordinary number caused the rest of the ensemble to seek more than they otherwise might have. Sam Champion and Josh Elliott, who share a CAA agent, were particularly aggressive in their asks. (Through their respective employers, both Champion and Elliott declined to comment.) In the lead-up to his contract negotiations, unflattering items about Elliott (who ultimately went to NBC Sports) appeared in the tabloids—that he was difficult to work with—and Elliott was vocal on-set that he suspected the negative leaks were emanating from ABC’s very own press office. According to multiple sources, the negotiations with Champion were so bruising that even after Sherwood eventually nearly matched a competing $2.5 million offer from the Weather Channel, the meteorologist opted to leave. A week after his teary farewell from the show, the Daily News ran an item quoting a “network insider” asserting that Champion had left ABC for money and power. According to multiple sources, Champion was livid to see in the item details of his Weather Channel deal that had been shared only with ABC upper management during negotiations. The item also asserted—falsely—that GMA’s weekend meteorologist Ginger Zee had been prepping for months to replace Champion.

Elliott’s departure—which ABC assumed came with assurances that Elliott would eventually replace Lauer—upset Sherwood deeply. Elliott had been central to his plans for the GMA turnaround Sherwood had sold Sweeney and Iger to land the news presidency. He released a statement free of the usual niceties. “In good faith,” Sherwood wrote, “we worked hard to close a significant gap between our generous offer and his expectations. In the end, Josh felt he deserved a different deal and so he chose a new path.” It was as close to a public screw-you as anyone can remember any network-news division ever releasing.

The moment Sherwood’s new job—overseeing a kingdom of television properties spanning six continents and with about 10,000 employees under his management—was announced, speculation about his next move began. “He’s relentless, he’s curious, and he’s incredibly competitive,” says Fusion CEO Isaac Lee. “But when he gets bored, he checks out. He goes on to the next thing.” For months, Disney insiders dismissed the notion that Sherwood, for his next act, was eyeing Iger’s chair, which the CEO had announced he planned to retire from in July 2016. Sherwood, they claimed, would have had barely a year in his new job, and the competition to replace Iger was internally seen as a two-man race between the corporation’s CFO, Jay Rasulo, and current parks-and-resorts chief Tom Staggs. Then, in early October, Iger suddenly announced he’d reconsidered this decision and would be staying on until 2018, which was seen by some as Iger simply loving his job and by others as an indication of the Disney board’s lack of confidence in his prospective heirs. Those who are loath to give up on imagining that Sherwood, the perpetual dark horse, could be Disney CEO mention that Iger and his predecessor, Michael Eisner, came up through ABC broadcast ranks and not in the theme-park business, as did Rasulo and Staggs.

The Disney/ABC Television Group that Sweeney has handed off to Sherwood—she literally passed him a runner’s baton on the set of The Chew during a December town-hall for Disney/ABC Television employees—isn’t nearly as problematic as ABC News was when Sherwood took over. Until this fall, ABC had been on the skids since 2011. But largely thanks to the Shonda Rhimes–dominated Thursday lineup, which includes Scandal and the new drama How to Get Away With Murder, ABC thrived in 2014, finishing No. 2 behind NBC (it would have finished first had sports been taken out of the equation). Even though Sherwood has borrowed a phrase he picked up from Sweeney, dubbing himself “a lucky general” for benefiting from decisions that he had nothing to do with, he’s benefited nonetheless. Exponentially benefited, in fact. “The network’s job one for him,” says superagent Rick Rosen, of William Morris Endeavor. “It’s only a small fraction of their television revenue, but right or wrong, the success of a broadcast network to major media companies is disproportionate to its impact on a balance sheet.”

In Rhimes, Sherwood may recognize a bit of Sawyer, in that though she nominally works for him, Rhimes arguably wields more power at the network than he does. (Over email, Rhimes reports that conversations with Sherwood have primarily been about “how ABC can be supportive of Shondaland’s needs.”) Rhimes’s importance to the network goes far beyond her shows’ importance to ABC’s ratings; unlike its hit Modern Family, which is produced and owned by 20th Century Fox Television, ABC Studios owns all of Shondaland’s shows. Disney pays 20th Century Fox for the rights to broadcast Modern Family and reaps significant money in advertising, but with Rhimes’s shows, not only is ABC paying its sibling division to produce the show but also the company gets massive payouts from owning the show, foremost in foreign sales and domestic syndication rights.

Come February 1, Sherwood will likely be devoting a good portion of his attention to ABC Studios. Thanks to the ascendancy of portable devices, and the proliferation of places like Amazon and Netflix, Sherwood sees ownership of content, per the Shondaland model, as paramount. Though ABC Studios already co-produces four Marvel Comics–related shows for Netflix and is developing a Civil War show for Amazon with Lost co-creator Carlton Cuse, it’s a distant third behind 20th Century Fox Televison and Warner Bros. Television in terms of hours of television produced. Sherwood has told associates he intends to narrow the gap at the very least. During the time he spent working alongside Sweeney, Sherwood scheduled long lunches picking the brains of Fox Studio co-head Dana Walden and Warner Bros. head Peter Roth, both of whose businesses, if Sherwood’s hopes are realized, he would overtake in the coming years. “He said, ‘I’m just getting my feet wet and I’m curious to meet you,’ ” says Roth. “I was flattered. It’s rare that I would get a call from an executive that senior for a get-together. From the moment I sat down, he asked me question after question after question. His curiosity was only matched by his charm.”

Sherwood has been prepping for a clean coronation, lauding at every possible juncture the amazing work that Sweeney has done in her decade at the job. (Sweeney’s departure, at 57, to begin a career as a television director was widely regarded as a concession when she discovered she was out of the running to ever inherit Iger’s job.) Last month, he led his first affiliate board meeting without Sweeney, in a conference room on the top floor of ABC’s 66th Street headquarters. According to a person present, Sherwood was short on details for his plans but went long on vision. He told them that it took some 400 years between the invention of the printing press and radio, but only a decade between the internet and smartphones, so that in the next century, we’d be experiencing the equivalent of 20,000 years of change. He quoted his own book, The Survivors Club, remarking that, like Admiral James Stockdale (the highest-ranking American naval POW in Vietnam), ABC would survive by employing realistic optimism in the face of great challenges. And while media figures like CBS’s Les Moonves now talk about going “over the top” and taking content directly to consumers via the internet, rather than the traditional local-affiliate path, Sherwood offered soothing words to the affiliates. He said he was bullish on the long-term survival of the traditional broadcast model, owing to its unparalleled reach into 116 million American homes, thanks precisely to the stations controlled by those seated before him.

Sherwood by now understands that the care and feeding of that restive group is one of the trickiest, most unpredictable parts of his new job. Of course, depending upon what he sees as his future at the company, there will be strong-willed members of another board he might consider charming and impressing, the Disney Board of Directors—Facebook's Sheryl Sandberg, Twitter's Jack Dorsey, among them—who, with Board Chairman Iger, will ultimately decide by vote who will lead the company. An executive close to Sherwood calls the notion that he’s looking beyond a job he’s yet to even start as “insane.” Still, those who’ve been surprised by him before insist that Sherwood will be on the move before long, either inside or outside of Disney. (Indeed, Iger is expected to soon name a chief operating officer to indicate his preferred successor.)

“Ben will get this job, do great at it, and then he’ll be looking for something else, whether he knows it now or not,” says Paul Slavin, who spent three decades as a producer at ABC News and lost out to him for the news presidency. “No job that Ben could end up in would surprise me.”

If all his wishes don’t come true inside the Magic Kingdom, Sherwood is way overdue on two books to his publisher, one on the lessons humans can learn from animals. Wherever he settles, as he likes to remind people, he will, as always, remain a storyteller at heart. In that ABC conference room, Sherwood told the affiliates before him that the championship would be theirs. “The sky is not falling on media,” he said. “The sky is rising.” That quote, he made sure to tell them, wasn’t a Sherwood original. They were words told to him by a very wise man, his boss for three more years, Bob Iger.

*This article appears in the January 12, 2015 issue of New York Magazine. It includes several small clarifications made after the magazine went to press.