Last week, Joe Biden made his first public appearances since the funeral of his 46-year-old son, Beau. His aides have said that his schedule will, for now, be flexible and that other top White House officials are gladly stepping forward to do what needs to be done while he observes his own rhythms of grieving. The press has been respectful and affectionate, as have most people on social media (a miracle of some kind); the only notable exception was Ted Cruz, who made a rote Biden joke on the campaign trail. Twitter responded with thousands of tiny bee stings. The senator promptly issued an apology.

There’s a school of thought that says elected officials are metabolically and psychologically different from civilians: They have larger appetites, more bountiful energy, bigger egos, greater desire for admiration. And it’s often true. But they remain as vulnerable to fortune’s left hooks as anyone, and they are just as devastated by loss, just as wretched in mourning. They lose parents. They lose spouses. They lose kids. And then they have to navigate their grief, one of the most intense and uncooperative of feelings — “no one ever told me that grief felt so like fear” is how C.S. Lewis put it — in a very public space.

Bill Clinton’s mother succumbed to breast cancer one year into his presidency (just the day before she died, the Times ran a piece about Gennifer Flowers and Arkansas state troopers trying to sell their lurid stories to New York publishing houses; it must have seemed like a dispatch from an alternate universe). Hillary lost her father while in the White House, too, and her mother died midway through her tenure as secretary of State. The night before his historic victory in 2008, Barack Obama lost his grandmother, who helped raise him. “I’m not going to talk about it too long,” he told his supporters, “because it is hard for me to talk about.”

Shortly after Beau Biden died, I called my friend Brian Baird about the peculiar nature of public mourning. Over the course of his 12 years in Congress, he lost his father to pulmonary fibrosis. He says the hardest part, to this day, is the second-guessing: He was immersed in a fairly brutal reelection campaign near what would turn out to be the end of his father’s life, and rather than spending the autumn with his dad, he spent it securing his job, because he’d been told his father still had a good six to nine months to live. Baird took the doctors at their word. He won his bid. He immediately flew out to see his father. “And the next thing I knew,” he said, “my dad was dying in my arms.” He thought he still had another six months.

But Baird, at least, was mourning someone he fully expected to mourn one day. The laws of nature applied. What amazed him, he said, was how many of his colleagues in Congress faced far worse. As he started rattling off a list of names and examples — people whose kids were gravely ill or dying, people who’d lost spouses or were tending to them — it was hard not to do the math and realize: A goodly number of the public officials we’re lampooning or harassing or complaining about daily are in fact concealing vast amounts of pain.

The experience of the California congresswoman Lois Capps stuck with me most. Her 63-year-old husband, Walter, died of a heart attack at Dulles Airport in 1997, just nine months into his first term in the House. She had no experience in politics, other than assisting with his campaign in the usual spousal ways, yet she felt a responsibility to run in the special election to replace him. When the L.A. Times asked her what it felt like to be campaigning so hard on the heels of her husband’s death, she responded honestly: It felt like there was a hole in her stomach. “Or words to that effect,” she told me over the phone. “Pretty dramatic and anatomical.” The next day, she opened the paper and was mortified. “I was trying to be seen as capable, and here was this enormous, revealing statement. I was totally embarrassed. And what I learned was to totally shut up. Which is a shame.”

Then, three years later, her daughter Lisa was diagnosed with lung cancer at 34. She lived 300 miles north of Capps’s district, which meant Capps faced the same dilemma as Baird. “I had to decide,” she said, “how much time I could spend with her.” She had obligations to her constituents and obligations in Washington, and her seat was vulnerable, having been held by Republicans for decades before she and her husband came along. “I think I was given permission to be as good a mom as I could,” she said. “And I was with her when she died.”

Yet here were the minor miracles: All of her colleagues — she truly thinks it was every single one — sent her notes or flowers, and they were remarkably tender toward her, mindful of her suffering (though some would inevitably say well-intentioned but not-consoling things, “like, This must be God’s will.”). And she discovered that she could get lost in much larger issues: “There’s a lot happening all the time in this job,” she said. “Pressing world issues. Or just issues my individual constituents faced. It was good to get back into something I knew.”

And this may be the saving grace for those who mourn while in public office — or rather, this may be why mourning while leading a public life isn’t as hard for politicians as a civilian might expect. It’s a business whose population self-selects. As a rule, elected officials thrive on a life of public interaction; they feel a calling to serve; they go after the job knowing full well that they’ll never have a peaceful moment at the supermarket ever again, because voters will be forever wandering up to them to complain or give them an “atta girl” or inquire about a Social Security check that never arrived in the mail. “If you run for office,” Capps explained, “you have to reach out to other people. You can’t do it as a solitary person. You derive strength and resources from being in public office, and comfort from losing yourself with other people.”

Not every elected official feels this way, of course. Some would no doubt benefit from a long, private bereavement leave. There are introverts in politics, just as there are in every profession, and no one can ever truly know how they’re going to respond to life’s pitiless events. But Biden has said before that it was, in part, the demands of his work — and his young sons — that made it possible for him to cope with his first calamitous loss 43 years ago, when his wife and baby girl died in a car accident.

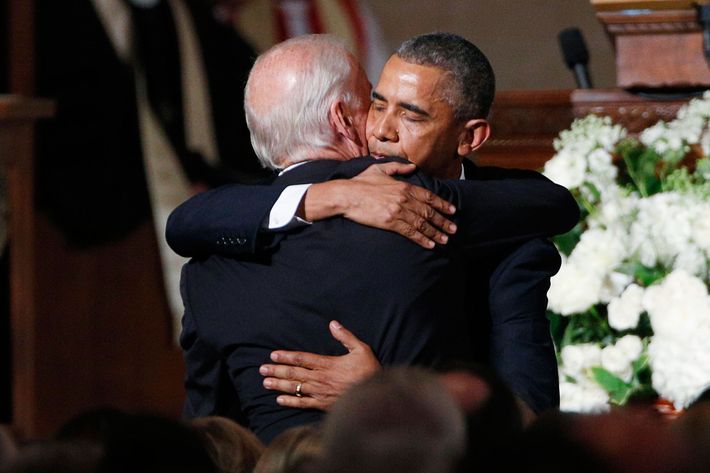

One day he may even come to talk about this most recent experience of tragedy, just as he has his previous ones. It’s already a big part of Biden’s legacy, illuminating what it means to grieve. It wasn’t the legacy he wanted. But it’s the legacy he has, and one could say it’s as valuable as any of the policies he’s championed. His only appearance this week was supposed to be at the White House forum on clean energy investment this Tuesday. Yet, after the shootings in Charleston, there he was at Obama’s side, mourning along with him. “I think we need to express ourselves more freely about loss,” Capps told me. “We need to learn to help one another in this area, rather than uphold a certain standard of behavior. Feeling vulnerable and weak and needy is not a bad thing.” Even in politics.