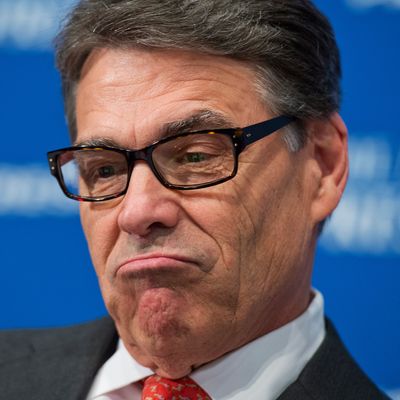

If you ask most conservatives why African-Americans vote overwhelmingly for the Democratic Party, they will typically reply that black people are either lazy moochers who want “free stuff,” or else they’ve been duped by a massive lie that the Democrats have become the party of civil rights. Rick Perry delivered an interesting speech last week, which continues to reverberate among conservative thought leaders, in which he made an important, if not unprecedented, concession. The historic defection of the black vote, Perry admitted, reflects the failings not of African-Americans but the Republican Party itself. Perry conceded that his party’s obsession with states’ rights, including his own, alienated a constituency that has depended on the federal government to protect its rights. This is an important admission about the Republican Party’s history. What Perry has failed to display is any grasp of how African-Americans have been turned away by the Republican Party’s present incarnation.

Perry makes two important, persuasive points in his speech but fails to see how they collide with each other. The first point is that states’ rights is a dangerous doctrine for African-Americans, who rely on the power of the federal government to protect them from abuses by states. Perry frames this as a confession that he has overemphasized the 10th Amendment to the Constitution, which reserves for the states or the people powers not delegated to the federal government, rather than the 14th amendment, which prevents states from denying any citizen equal protection of the laws. “There has been, and there will continue to be, an important and a legitimate role for the federal government in enforcing Civil Rights,” Perry said, “Too often, we Republicans, me included, have emphasized our message on the 10th Amendment but not our message on the 14th.”

Perry’s second point is that urban policy often works to the detriment of the disadvantaged. “In blue state coastal cities, you have these strict zoning laws, environmental regulations that have prevented buildings from expanding the housing supply. And that may be great for the venture capitalist who wants to keep a nice view of San Francisco Bay. But it’s not so great for the single mother working two jobs in order to pay rent and still put food on the table for her kids.”

Perry frames the latter as an indictment of government in general. But it is actually an indictment of localized government regulation. This is an aspect of government policy where Perry can legitimately boast that his state has outperformed the blue-state model. Deregulated zoning has allowed Texas to create affordable housing that is denied residents of big coastal cities.

Perry does not connect these two notions, but they both support the same conclusion: The worst excesses of government all reside at the state and local level (an argument I’ve made in more detail before). Voters know much less about their state and local representatives than their national ones, and many city elected officials are insulated from accountability by one-party rule. States and localities enact the most economically burdensome regulations on entrepreneurs and housing, and carry out the most oppressive forms of law enforcement. It would be logical to conclude that the Republican path to rebuilding support in the black community lies in redirecting its efforts toward reducing onerous government where it exists: at the state and local level.

Instead Perry draws the opposite conclusion. He confirms his commitment to the ancient conservative doctrine of devoting more power to the state and local level. Perry proposes turning anti-poverty spending into “a block grant so that states can care and put into place that safety net for their population in a manner that best serves their citizens.” In education, he decries a “one-size-fits-all mentality in policy,” proposing to “empower state lawmakers, the school boards, the parents.”

Empowering state and local governments would make African-Americans more vulnerable to the whims of the very governments that have served them poorly. The state and local tax base is highly regressive, with Perry’s Texas being among the worst offenders. (The poorest 20 percent of Texans pay 12.5 percent of their income in state and local taxes; the richest one percent of Texans pay 2.9 percent of their income in state and local taxes.) States erect bureaucratic obstacles to winnow low-income potential voters from the electorate; Texas has continued its long history of such behavior.

Steamrolling historians’ objections, Texas has also imposed revisionist historical analysis upon its textbooks, downplaying the central role of slavery in the Civil War. Republican-controlled states, including Texas, have chosen to leave their citizens uninsured rather than accept federal funds to expand Medicaid. (Perry briefly justifies this choice by implying a person is no better off on Medicaid than remaining uninsured, which is absurd.) He denounces federal spending on the poor as excessive and useless — “Today we spend nearly one trillion dollars a year on means tested antipoverty programs. And yet, black poverty remains stagnant.” (In fact, the trillion-dollar figure is a gross exaggeration, and his implication that it’s failed to reduce poverty is utterly false.)

Perry’s plan is to weaken the parts of government that have done the most to safeguard African-American rights and interests, and to strengthen the parts of government that have ignored or trampled them. “Blacks know that Republican Barry Goldwater in 1964 ran against Lyndon Johnson, who was a champion for civil rights,” he says, “They know that Barry Goldwater opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” There will come a day when a Texas Republican courts black voters by apologizing for Rick Perry.