Earlier this summer, in considering the appeal of a longtime California death-row inmate named Hector Ayala, Justice Anthony Kennedy set aside the substance of Ayala’s appeal (it had to do with the circumstances under which a judge could exclude members of the jury pool), and instead fixed on a matter peripheral to the case and barely mentioned in the testimony: Ayala’s long tenure in solitary confinement, where the inmate has spent most of the past two decades. Ayala, Kennedy wrote, has “likely been held for all or most of the past 20 years or more in a windowless cell no larger than a typical parking spot for 23 hours a day; and in the one hour when he leaves it, he likely is allowed little or no opportunity for conversation or interaction with anyone.”

Something in the Ayala case stirred Kennedy, though the strange opacity of the Supreme Court means we can’t really know what it was. As Kennedy’s opinion noted, there are about 25,000 people in solitary confinement in the country; Ayala’s circumstances were neither well described in the court record nor unique. But his concurring opinion quoted Dickens and cited the dehumanizing treatment of Kalief Browder in New York; he had his law clerks dig up an 1890 case in which the Supreme Court had decided that even for those prisoners sentenced to death, solitary confinement contained a “particular terror and a peculiar mark of infamy.” Kennedy closed by quoting Dostoyevsky: The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons. Then the justice wrote, “There is truth to this in our time.”

In the weeks since Kennedy’s exhortation, solitary confinement has seemed, for the first time in many years, to have eclipsed capital punishment as the most urgent subject of criminal-justice reform. The president, speaking at the NAACP convention at the end of July, raised the issue: “Do we really think it makes sense to lock so many people alone in tiny cells for 23 hours a day, sometimes for months or even years at a time?” The practice, Obama concluded, was “not smart.” Last week, the Times devoted a long profile to Craig Haney, an academic psychologist who has spent 20 years studying the effects of long terms in solitary on inmates at California’s notorious Pelican Bay prison — people who, in Haney’s words, have undergone a “social death.” There is even a detectable movement against it, spurred by the profiling of the Pelican Bay strike and of cases like Browder’s: 14 states, as the Marshall Project has documented, curtailed their use of solitary in 2014 alone.

Why this focus now? For most of the past half-century, the single moral cause of the prison-reform movement, to the degree that such a movement has even existed, was death-penalty abolition. This had success in a few state-by-state legislative bursts, and has surely helped to slow the overall rate of executions, but has been far from a comprehensive success: 31 states still execute their prisoners. But during that half-century of worthy labor by abolitionists, the prison system has radically expanded and changed shape, in ways that have little to do with the execution chambers. People convicted of crimes have stayed in prison for much longer, and there are far more of them, and use of the peculiar administrative tool of long-term solitary confinement has grown. In his opinion, Justice Kennedy observed that a great deal of attention was paid to adjudicating a defendant’s guilt or innocence, but that “too little attention has been paid to what happens next.” But recently that public emphasis has seemed to subtly change, from the death penalty to solitary confinement, and a far more direct encounter with the problem of mass incarceration.

Two years ago I wrote a long, narrative report on the largest prisoner hunger strike in American history, which began from within the solitary confinement unit of the Pelican Bay prison and spread to 60,000 California inmates throughout the state. Several dozen prisoners, including the strike’s four leaders, each a prominent gang leader (Todd Ashker, Arturo Castellanos, Antonio Guillen, and Sitawa Jamaa), refused all food for two months straight, and the strike ended only when a judge issued a court order allowing prison officials to implant feeding tubes if necessary.

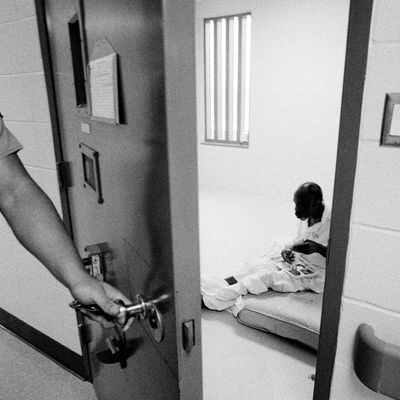

To see Pelican Bay’s vast, sterile solitary confinement wings, to witness the ways in which this form of imprisonment lightened the skin of inmates and (in some cases) made them crazy, to notice the ever-present fear of the prison guards — all of this clarified the purpose of these places. They are not a means of vengeance, like the death penalty, but tools of administrative control, ways for wardens to get their arms around a system that is too big to manage. No jury or judge participates in the decision to put a prisoner in solitary. The longest tenures are not reserved for inmates who have committed especially violent acts outside the prison, or even for those who have committed assaults or murders inside. They are all issued for simply belonging to a gang, because gangs are the destabilizing force within the California prisons, the chaotic element that can make what is always an extremely difficult project of social control completely impossible.

In every particular, the expansion of solitary and the problem of mass incarceration are linked. The case of Kalief Browder (who spent about two years in solitary before his case even came to trial, and eventually committed suicide) showed both how absolute the power of the state over an incarcerated inmate can be, and how accidentally that power can be attained. When New York published a lengthy report on Rikers Island this summer, one theme running through it was the disorder that had spread after a progressive policy shift had eliminated solitary confinement for juvenile offenders. That’s anecdote, not data, and the evidence that solitary actually suppresses prison violence is not very strong. But still you can see the psychological appeal: Solitary means there is something worse that can be done to inmates if they make the prison a more violent place, that there does exist some force of discipline and punishment. It gives the prison officials the image of control.

In the rolling Black Lives Matter protests, you can see a movement against mass incarceration beginning to define itself, and find a shape. But it’s interesting that of all the justices, it was Anthony Kennedy (the Supreme Court’s most centrist figure) who turned to moral exhortation — suggesting that the problems surrounding mass incarceration might come to outrage Americans generally, and not just social progressives.

To Kennedy’s sense of a “new and growing awareness” of solitary confinement, I’d add one more, complicating point. Public outrage around mass incarceration tends to swell when its injustices are made vivid: When a person who is actually not guilty of a crime (like Browder) is condemned to a life in a box, when the racial disparities in enforcement or punishment are fully revealed, when nonviolent drug dealers are locked up for most of their adult lives.

But in a sense these are the easy cases. As experts have been suggesting recently, freeing the nonviolent isn’t likely to cut the prison population by all that much. America is still a very violent country. The most difficult moral question surrounding prison reform isn’t how the state treats the innocents, or the nonviolent. The hardest question is how we ought to treat the many very violent prisoners, the gang leaders and those who are actually guilty: the Hector Ayalas, the Todd Ashkers, the Arturo Castellanoses, the Antonio Guillens, the Sitawa Jamaas.

It isn’t obvious what would happen to murderous prison-gang leaders if the movement against solitary continues: Perhaps they’d simply live out their days among the general population, or perhaps a more active movement against mass incarceration would mean shorter sentences for violence, and their eventual release. What to do about people with long records of genuine violence is the hardest question in the whole arena of crime, and the most stubborn issue in the social science that surrounds it. But campaigning against capital punishment doesn’t really begin to answer that question. Trying to fix solitary confinement does.