Over the last few years, as mainstream concern with the war on drugs and mass incarceration has grown, a relatively straightforward narrative has taken hold: White people, engaged in a backlash against the advances of the civil-rights era, imposed the carceral state on black people. That’s the story told by Michelle Alexander in her seminal book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, as well as by any number of other academics and public intellectuals.

To many people, New York’s Rockefeller Drug Laws epitomize this sad trajectory like no other piece of legislation. Passed in 1973, they imposed harsh penalties on those convicted of drug-related offenses, including mandatory life sentences for the sale of many hard drugs and harsh sentences for possessions of small quantities. Between their enactment and 2009 repeal, they were responsible for a massive wave of incarceration over minor drug convictions — one that disproportionately targeted black and Latino New Yorkers.

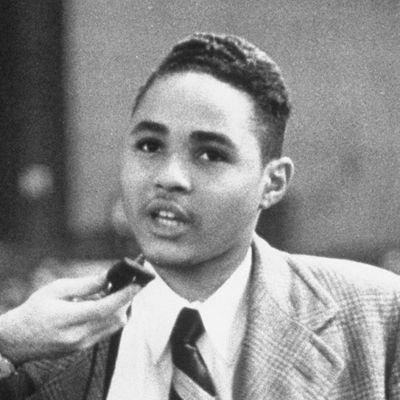

Michael Javen Fortner, a political scientist at City University of New York, is hoping to complicate the story that the Rockefeller laws, and others like them, were foisted on black people by white people. His book, Black Silent Majority: The Rockefeller Drug Laws and the Politics of Punishment, out September 28 from Harvard University Press, tells the story of Harlem’s struggles with drugs and crime from the 1940s through the passage of the Rockefeller laws. Key to this story is the role of Harlem’s residents in forcefully advocating for a tougher, more punitive approach to the neighborhood’s “pushers” and addicts.

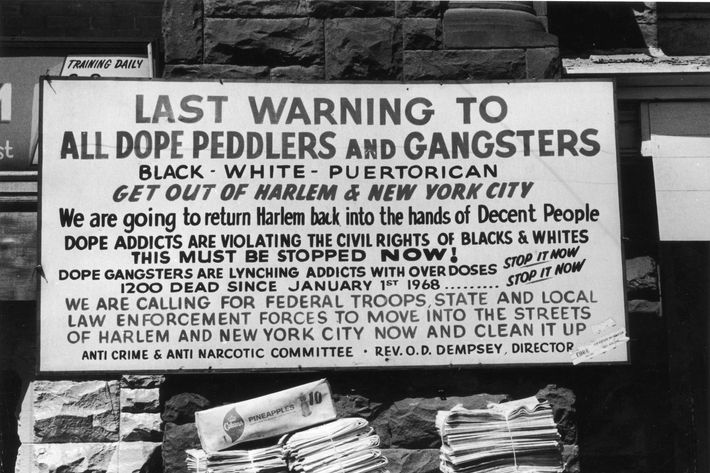

Harlem experienced a devastating, drug-fueled increase in crime in the 1960s that peaked around 1971 — one that included countless grisly murders, muggings, and burglaries (seemingly every other Harlem community activist mentioned in Fortner’s book was victimized at some point). The chaos, which occurred against the backdrop of a steady stream of overdoses and the other physical ravages of drug addiction, helped mobilize figures like the Reverend Oberia Dempsey, an influential tough-on-crime African-American activist in Harlem who at one point implored the city to “Take the junkies off the streets and put them in camps.” It also spurred the creation of organizations like Mothers Against Drugs and Citizens’ Mobilization Against Crime (founded by the author of an influential NAACP anti-crime report), as well as other groups that went as far as launching armed patrols to help protect Harlem’s residents from criminal activity. One woman, whose 18-year-old daughter died from an overdose, “kept repeating ‘Kill the pushers’ when asked what should be done,” Fortner writes.

These attitudes and initiatives were part of what Ebony described at the time as “a backlash against the heavy drug traffic in [black New York] communities and against all who benefit from it.” It was a backlash fueled by Fortner’s “black silent majority” of Harlemites fed up with the crime and addiction they saw all around them — a play off Richard Nixon’s concept of a broad swathe of Americans who had generally kept quiet about politics, but who approved of his approach to the Vietnam War (it’s a phrase that Donald Trump has used a few times, and which many people view as a racial dog-whistle aimed at conservative whites).

In Fortner’s telling, the black silent majority’s heightened sense of anger, fear, and despair greatly attenuated the appeal of the so-called “old penology” favored by white liberals (as well as a lingering minority of black voices), which emphasized treatment and rehabilitation over punishment. While Fortner argues that it isn’t quite fair to say that the old penology had failed — to the extent treatment-centered approaches were tried in mid-century New York, they were likely doomed from the start by a lack of funding and improper implementation — once this attitude had hardened, it pushed Harlemites to seek enforcement- and punishment-heavy responses to help stabilize their neighborhoods.

This change in public opinion extended to the Rockefeller laws themselves. While they were passed partially as a result of perennial presidential candidate Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s attempt to paint himself as conservative, this is only part of the story. The governor himself was lobbied by influential voices within Harlem to get tougher on drugs, and once he did, black New Yorkers appreciated it — a New York Times poll taken after the dust from the laws’ passage had settled found that “71 percent of black respondents [in New York City] favored life sentences without parole for pushers.” (“A poll that no one seems to mention when they criticize my book,” Fortner said.) Contrary to popular belief, Fortner argues, the laws were not passed as a result of a sudden white interest in controlling black crime (and black people); rather, Rockefeller took a discourse that had been developed by black activists and citizens — one couched in emergency and the failure of “the old ways” of handling addiction and crime — and exploited it toward his own political ends.

Fortner’s point is not that these laws were a good thing — he acknowledges the tremendous harm they did, and writes with regret about their heavily racialized impact. But he said he’s frustrated by a narrative that robs African-Americans of their agency, that acts as though black concerns over crime are somehow illegitimate. He also emphasized that while he thinks the white-black aspect of the Rockefeller laws has been overstated, institutionalized racism is in fact a key part of this story, simply because black people, thanks to racist housing practices, didn’t really have the option to leave Harlem; there was no black equivalent to white flight out of distressed areas. “Residential segregation trapped people — both people who had jobs and those who didn’t — within the same social environment,” he said. “And then you had crime and drugs and a host of vices manifest themselves, and the black middle class and working class have little recourse because they can’t move. So they have to confront these difficulties, right? And over time they grow more punitive in their approach to these challenges.”

In the book’s conclusion, Fortner explains that “According to the black silent majority, white liberals, from their privileged perch within the racial order, suffered from ideological vainglory and a class-based myopia, which led them to fight on behalf of addicts and pushers rather than the city’s working- and middle-class black citizens.” He sees echoes of this divide in the current debate sparked by the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement — albeit a more class-centered version.

Overall, Fortner said he appreciates what the movement has done. “I think we’re having a very important conversation about police brutality,” he said, and he credits BLM with “forcing people and politicians to recognize both this problem and the dignity and worth of black folks in general. And I think that’s a great thing.” But he also argued that the BLM conversation ignores the very real effects crime has on certain neighborhoods. “I think it tends to minimize street violence and some of the terror that many poor people of color endure within urban communities throughout the United States, and that it doesn’t speak to the violence against their lives that is not the product of the state but is done by people that look like them, people from their neighborhood, people from their communities,” he said. “And I wish that would be a larger part of the conversation. Not to say it should replace the conversation, but that the conversation should include all types of violence that destroy and undermine the lives of poor people of color in urban communities. “

To Fortner, who grew up in Brownsville, Brooklyn, at a time when it was being battered by the crack epidemic, and who doesn’t have any memories of a brother who was stabbed to death when he (Fortner) was about two years old, the black silent majority remains an important concept, but the fact that African-Americans have somewhat more options about where they can live has changed the geographical equation. “I think what’s slightly different from back then is that now lower-class people have been able to move,” he said. “So you have people like me who have been able to leave the ghetto, who have gotten fancy educations, and right now, I don’t live that close to crime. Crime doesn’t affect my life in a very present way, so if I was just gonna follow my ideological instincts, then I would be saying we should focus on police brutality … But I do think that if you do go to the projects in a lot of these communities and talk to the people who are not there during the day because they’re at work but have to come home at night, I think you may hear some of this silent black majority.”

Fortner said he sees this class divide over crime and policing play out daily on his Facebook and Twitter feeds. “I have a lot of black friends from Ivy League schools who are part of finance or academics, and they are completely on the left on this, focused on police brutality,” he said. “And then I also have some people, friends from when I was growing up, relatives — they have a much different view of these issues. Again: The black culture is concerned about police brutality, but there is some more balance in terms of their emphasis on the crime and their experience in their daily lives, and I think that’s missing from this conversation.” (Richard Sherman and Michael Bennett recently debated this very issue via statements to the press.)

Lurking underneath Fortner’s intricate, careful parsing of the historical record, then, is a simple claim about human beings: If you live in a neighborhood where you feel like you, your family, and your possessions are perpetually at risk, it will harden your politics and your view of your neighbors. Fortner’s main goal is to remind readers that this isn’t just true of white people.