Baltimore After Freddie Gray: A Laboratory of Urban Violence

A year after his death, murders in the city have soared, and the relationship between violence and policing has never been more complicated.

Part I

On the clear April afternoon when the Freddie Gray riots escalated, most members of the city’s political Establishment were inside the New Shiloh Baptist Church in West Baltimore for the funeral of Gray himself. They might as well have been in a box. Gray, the 25-year-old man whose spine had snapped after he was handcuffed and allowed to bounce around inside a police transport van, had been anonymous in life, but in death his invisibility had made him a symbol of the vulnerability of African-Americans in Baltimore and beyond. The police commissioner did not attend the funeral, but the Reverend Jesse Jackson did. So did Elijah Cummings, the ranking Democrat on the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee. Nearby was Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake — young, a modernizer, the president of the U.S. Conference of Mayors. There too was her popular predecessor, Sheila Dixon, removed from office amid scandal but contemplating a run to reclaim City Hall.

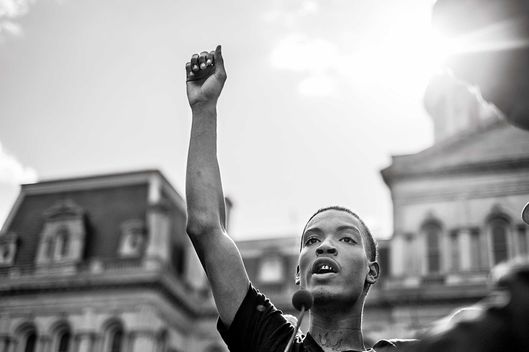

It was obvious already that Gray’s death had revealed a rupture in Baltimore — since he had fallen into a coma, there had been protests or vigils just about every day, small at first, then growing larger — but its extent was not yet clear. Many of the first protests had been led by an unknown 26-year-old storefront preacher named Westley West, who presided over street funerals at no charge, and so the initial images of the movement centered on a young man of no reputation and no direct relationship to the Gray family marching toward the Western District police headquarters with purpose, a huge crucifix swinging from his neck and his brother shouting in his ear. By the time of the funeral at New Shiloh Baptist, some members of the Gray family were relegated to the balcony, and behind them sat Gray’s neighbors from the Gilmor Homes housing project. The balcony, though, turned out to be a good place from which to see what happened next: everyone surreptitiously checking their cell phones for news of the insurrection growing outside.

Among the mourners in the church was a man named Ted Sutton, once a close associate of the legendary West Baltimore gangster Little Melvin Williams and now a youth pastor and an anti-violence advocate. He left the funeral and gathered a group of men to try to locate the protesters. They traveled first to Mondawmin Mall, but it was quiet. Then they came closer to the center of the city, to the corner of Fulton and North Avenues, which wasn’t quiet at all. The police had massed in riot gear, but then they had fallen back, unsure about what their posture ought to be. The protests during the past week had been organized, with slogans and signs, but here there was more chaos and confrontation. Sutton remembers seeing an Asian liquor-store owner being beaten; he intervened and called an ambulance and the man’s son. But within this disorder, Sutton, a student of the relationship between power and violence, also noticed signs of intent. He saw a cluster of small businesses on North Avenue (a hardware store, a dry cleaner) that belonged to his old mentor, Williams, who had long ago sworn off crime. None had been touched. The targets seemed mostly to be chain stores or those owned by outsiders. Sutton thought this was a good sign; it meant the protests had some discipline and direction.

Anywhere in the world, anytime police line up in riot gear across from a crowd of citizens, the space between them becomes a stage. A teenage boy walked into the middle with his arms out. The police had been firing pellets into the crowd. “Shoot me!” the boy was crying out. “Shoot me!” Sutton became alarmed. He recognized the boy, whose name was Nehemiah; he was a student whom Sutton had mentored at a West Side middle school. Sutton, six-foot-four and broad, pushed through the crowd and ran out to the boy. “Nehemiah, this isn’t a game! They’ll kill you!” he yelled. Together with one of his men, Elder G, Sutton pulled Nehemiah back from the stage and returned him to the crowd. Then

a police officer fired a tear-gas canister toward the protesters, and it became difficult to see.

Everyone in Baltimore seemed to get arrested that day, April 27. By the end of the evening, the city jail was packed — eight-man cells held 16, two-man cells held four. A nursing home being built on the East Side was torched, though no one was ever arrested for the arson, and the motives remain inscrutable; crowds looted pharmacies and clothing stores up and down the West Side; late into the night, cars full of young men circled slowly in prosperous neighborhoods; the television cameras were ubiquitous, unmissable symbols of the broader world’s interest. No one went home and no one died.

Each of the American cities where high-profile police killings have inspired demonstrations these past three years has had a different experience of violence, of political protest, of social change — each is part of a composite. Baltimore’s has been the most prolonged: After Gray’s killing, and then after the protests, there was a third phase, more devastating than anywhere else, in which the police seemed to retreat and then the largest wave of homicides in a quarter-century overwhelmed the city. That wave has still not fully subsided; the disturbance that became visible with Gray’s death continues.

There was something else unique to Baltimore’s experience that deepened its tragedy and mystery. Baltimore’s political leadership is composed almost entirely of progressive African-Americans, many of whom had marched in Black Lives Matter protests. Under their watch, zero-tolerance policing had been curbed, and, for the first time in many years, the city had grown more prosperous and inviting and people had been moving in rather than out. Even so, there was no large personal distance between these figures and street violence. Representative Cummings spoke at Gray’s funeral about his own nephew, murdered at college, whom he memorialized at Victory Prayer Chapel in Baltimore: “Every day I mourn what could have been.”* The nephew of the City Council president, Bernard Young, had recently been murdered, too. And so what followed the demonstrations in Baltimore was more complicated than what happened in Sanford, Florida, after 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was shot by a neighborhood-watch volunteer; or in Ferguson, Missouri, after the police shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown: outrage, but also self-doubt. The gaze in Baltimore went inward, not just to the politics of race and violence, not just to the social structures that shaped those politics, but to the emotional terrain underneath.

On the afternoon of April 28, a senior police official named Melvin Russell took an unusual call from a friend. A private meeting of rival gang leaders, who had themselves been disturbed by the violence within the protests, was about to begin, and the friend thought Russell would want to be there. Russell, a lieutenant colonel who runs the department’s community-relations division, grew up in Baltimore and has been an officer in the city since 1981. Since the protests began, he had spent far more time in meetings than he would have liked, and so his experience had a nightmarish quality, “like I was watching someone dying in the street, a few feet from me, but could do nothing about it.” The friend gave an address — a church in Northwest Baltimore — and said not to tell the press. Russell called some members of Gray’s family to encourage them to come too. Then he went.

Someone told the press. As Russell arrived, there were camera vans out front, so he slipped in the back door. “We lost the members of the Gray family at that time, because they pulled up and saw the cameras,” Russell told me. They lost a few gang members, too. But eventually the reporters left. Inside the church, there were representatives from the three major Baltimore gangs: the Bloods, the Crips, and the Black Guerrilla Family. They looked at Russell — a tall African-American man in his 50s who wore his authority heavily —“cross-eyed.”

The gang leaders had arrived with a specific grievance. As the first protests had unfolded, someone in the police department had told a reporter that they had been organized by Baltimore’s gangs in order to attack cops. The report spread: It was broadcast on Fox and made headlines in several papers. The gang leaders were furious. One man from the Crips faction relayed a story: When the teenagers were coming down Pennsylvania Avenue, some Crips saw a cop outside his car. “And they said, ‘Get in that business quick,’ because he wasn’t close enough to his car,” Russell said. The crowd destroyed the car, but the officer had heeded the Crips’ warning and hid. “So this guy”— the Crip —“was emotional about this. He said, ‘How are you saying we tried to kill cops when we were saving their lives?’ ” This went on for a while. Russell said, “They were absolutely right.”

The meeting lasted an hour and a half. Eventually conversation turned to what might be done. Russell asked that representatives of the gangs meet him at the corner of Pennsylvania and North each evening at nine to help disperse the crowds. Each night that week, Russell saw them out as promised: the Crips in their blues, the Bloods in their reds. The Black Guerrilla Family doesn’t wear colors, but he recognized their faces.

The violence that first week was often symbolic, but because the cameras were everywhere, it was all on television. Not far from where Ted Sutton had waded into the crowd, and not long after, a CNN reporter was interviewing a street activist named PFK Boom. “The people in my city are not happy,” he declared. Then, in the background and on live television, a tall man in a bright-pink hoodie sliced open a hose that firefighters were using to put out a blaze. For a few seconds there was pandemonium — it was hard to tell what had happened — and then the camera focused on the same man, his face covered by a gas mask, as he stabbed the fire hose again with a knife and water spurted into the air. The young man bounded away.

According to the police account, that same man was arrested a few hours later when he walked into a corner store while possessing a weapon. (The police believed he was there to loot the place, though his lawyers would argue that he intended to help protect it.) His name was Gregory Butler Jr., then 21 years old and from the East Side, and he had been a basketball star headed out of the city until an administrative detail cost him an athletic scholarship: Baltimore’s schools, unlike most, give no extra weight to the honors classes Butler had taken, and so his GPA was too low to qualify. Since graduating, he had generally stuck close to his own neighborhood, but the Gray protests had loosened something in him. He had attended most of them, shouting alongside young men from other neighborhoods he would have usually avoided, sensing the familiar fears of street violence dissipating. Even after his arrest, in the city jail, he found that “most of the conversation was political. There was no fear.” Later in the summer, Butler would attend youth-activist forums, speaking with feeling of the “hopelessness” of the children in his neighborhood, of the necessity that someone mentor them.

It says something about the sheer confusion of the moment, of the ways violence upended all of Baltimore’s normal moral categories, that during the last days of April, Greg Butler Jr. was the force of nihilism and chaos and the Bloods and the Crips the forces of order.

This confusion of categories was everywhere. It was hard to distinguish between the rioters and the protesters, or discern whether these grievances were simply part of the national activist wave. But from up close, there was less surprise; the events had a specific, local history. “You could see this coming,” Russell said, “for about two years.”

The summer of 2013 had a particular significance to many activists in Baltimore, because that was when an unarmed 44-year-old man named Tyrone West died after being beaten by at least eight Baltimore cops, according to a lawsuit his family later filed. West had been pulled over while driving his sister’s Mercedes-Benz; police would later say he’d been moving furtively inside and that they’d found cocaine tucked in his sock. Told to sit on the curb, West got angry, stood up, and started fighting the police, according to the account of a passenger in his car. It took ten minutes for him to succumb.

The city prosecutor declined to charge any policemen; a key component in West’s death, the coroner eventually ruled, had been a heart condition. To West’s family, this seemed like an evasion. His sister, Tawanda Jones, organized a vigil seven days after his death, and then another one seven days after that. The vigils became small weekly demonstrations against police brutality, and soon she began moving them around the city, into its most violent neighborhoods. West’s name resonated across the city. (PFK Boom would mention him on CNN.) So did that of Anthony Anderson, a 46-year-old man killed in 2012 when a police officer tackled him from behind, rupturing his spleen. Anderson collapsed in front of his mother, sister, son, and daughter and died minutes later. Like West’s, his death had come in an everyday setting.

Jones was unrelenting. “We went to every public meeting,” she said. But as the weekly protests continued, West and Anderson became not just examples of police brutality but evidence that the city’s leadership could not be trusted to correct it. And then came Freddie Gray.

A similar unease, a worry that terrible things could happen to ordinary people, moved through the police department after six officers were charged with killing Gray. His death was different from Brown’s, or Tamir Rice’s in Cleveland, because it was caused not by the violent action of a single officer but by an accumulation of negligence. Gray, who had five pending drug charges against him, had bolted when a bicycle cop turned toward him, and he’d been chased down, subdued, and handcuffed. Then he was placed in a paddy wagon without being seat-belted. Gray allegedly called out for a doctor, but by the time the paddy wagon stopped and a sergeant opened the back door, he did not respond. The sergeant did nothing, and within 12 hours Gray was in a coma.

That sergeant’s name was Alicia White, and when it was announced, the leader of a local community group where she had once patrolled expressed her astonishment to reporters, saying that White had been a model cop, that she had volunteered her off-duty time to community cleanups and events. When the news of White’s involvement hit Russell’s department of community–policing evangelists, he found himself comforting several crying members of his own staff, “women and men both.” The normal moral categories had collapsed for them, too. The usual line, that police brutality was the work of a few bad cops, was harder to accept without reservation when you knew one of the officers involved and she seemed like a good cop.

Part II

Thursday evening, just before the citywide curfew, a tractor-trailer driver was found dead, slumped behind the wheel of his rig parked on Pennsylvania Avenue, less than a block from the burning CVS. Police roped off the crime scene, said the death was suspicious, and for a moment it looked like the symbolic, politically fraught mayhem of the riots might have turned into something else. But an investigation found no signs of foul play. False alarm.

On the evening of Gray’s funeral, as Pennsylvania and North burned, Mayor Rawlings-Blake held a press conference, in part to plead for order. “It is very clear,” she said, “that there’s a difference between what we saw last week between the peaceful protests ... and the thugs who only want to incite violence and destroy our city.” That single word — thugs — stood out right away as a mistake. In setting the streets against the community, Rawlings–Blake misunderstood the basic shape of the outrage, which was that the distance between the streets and the community had collapsed. Rawlings-Blake also missed something even larger: The entire city had been upended.

For most of the past decade, Baltimore has averaged about a homicide every other day, and that had been the pace for the first four months of the year. After the demonstrations, the violence escalated immediately. On Tuesday the 28th, as the protesters progressed at Pennsylvania and North, there had been two incidents in short succession in Park Heights, in Northwest Baltimore, just west of Pimlico racetrack: First, a 31-year-old woman was shot; shortly thereafter, two men were shot, one fatally, leaving a trail of blood outside the shops on Park Heights Avenue. The next day, five people were shot, three of whom died; the day after, there were three more shootings and two more homicide victims. The shootings were all over the city, but as they accumulated, they clustered in West Baltimore near the sites of Freddie Gray’s death and the riots. That Thursday, there had been a brief media scrum on Mosher Street, where the police van carrying Freddie Gray made a previously unreported stop before traveling on. Shortly after the journalists left, a 19-year-old man was shot on the same block. The next day, another man was murdered two blocks from the Gilmor Homes, with protests going strong on North Avenue nearby.

The killings continued. On May 3, there were two; on May 4, two more, one of them a stabbing witnessed by a technology columnist for the Wall Street Journal and his fiancée, who lived in the area and were biking to Whole Foods. On May 7, two people were killed; on May 10, four more; and on the 14th, four more still. On the 20th, a rapper called Nazty was killed, one victim in a quintuple shooting, and Westley West, the young street preacher, prepared for the funeral sermon by reading Nazty’s lyrics, trying to piece together the personality of a man he did not know. On the last day of May, three men were killed, two of them in a shooting as a cookout ended. One victim was a 22-year-old man named Ronnie Thomas III whose 14-year-old brother had been killed 13 months earlier. In ordinary times, Baltimore is a very violent place, but this was exceptional. Forty-two people were killed in the city in May, the most in a calendar month since the peak of the crack epidemic. In July, there were 45 more murders.

The most intense demonstrations, the ones that provoked the city to establish a curfew and the state to send in the National Guard, lasted only a week, and they broke soon after Marilyn Mosby, the city’s young and politically connected chief prosecutor, announced charges against the six officers involved in Gray’s killing that ran up to second-degree murder. They were indicted three weeks later. That Sunday, Russell was at his in-laws’ house when his mother-in-law congratulated him, having seen his name in the Baltimore Sun. The police commissioner, Anthony Batts, had said that Russell would be sent to the Western District to repair the relationship between the police and the most violent neighborhoods in the city. Russell said he had not heard of this before. He was to be the police department’s olive branch. “I said, ‘Well, ain’t this but a butter biscuit.’ ”

Russell was in his own way as suspicious of police culture as Tawanda Jones was, though his suspicion was more surprising since he helped to run the department. “I’m so discontented with the police,” he told me. Russell had been the first African-American valedictorian of the city’s police academy in 1981; though Baltimore is nearly two-thirds black, it took two more decades before there was a second. He worked narcotics for most of his career, and his rise through the ranks was slow. At one point, Russell failed the lieutenant’s exam. “I come to find out that all the Anglo officers had been given the exam questions beforehand,” he told me. Russell has six sons and two daughters. When one of them was “accosted and jacked up by police — would have been abused if he didn’t blurt out my name,” Russell and his wife, Lolita, decided to move their family out of the city. “I couldn’t protect my six African-American boys in Baltimore,” he said, from either violent crime or the police.

They considered Pennsylvania, but too many Baltimore cops lived there already. “When I retire, I don’t want to see any police,” Russell told Lolita. They settled on Delaware. “I knew only one other [Baltimore] policeman in the state, and he lived in a different city,” Russell said. “So I felt safe.” Then he had a change of heart. Probably he was too energetic to retire. There was another lieutenant’s exam coming up, and Russell took it, passing easily, and he considered this a sign. The zero-tolerance policing of Mayor Martin O’Malley’s administration, which in one year saw more than 100,000 arrests in a city of 640,000, had been scaled back. Russell became deputy commander of the city’s Northwestern District, then commander of the Eastern. When violent crime declined in both places, he had the attention of the then–City Council president, Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, and, through her urging, a citywide post.

Once Batts sent him to the West Side in May, Russell was there almost all the time, mostly alone. It was a hostile place. West Baltimore has always been the city’s heart, the center of the old fights over residential segregation, the site of the biggest heroin markets, and, on its periphery, still home to much of the remaining urban black middle class. “East Side’s the least side — West Side is certified,” the saying goes. But the Western District had been transformed by the time Russell arrived. The six indicted officers had been suspended from their shifts. Among those who remained, Russell said, there was a feeling that “the whole world was against us.” On the streets, patrolmen told Russell that when they tried to make routine traffic stops they’d be surrounded by dozens of people holding up cell-phone cameras and shouting, “Don’t Freddie Gray him!” When Russell himself walked through the Gilmor Homes, people would shout at him, “Fuck the police!” He heard it from men, women, and children. Russell had been working in Baltimore since before the crack epidemic. He’d never heard anything like that. “I was so freaked out by the lack of communication,” he said.

Russell made a few phone calls to his old contacts all over the city — to pastors, to community activists, to sergeants he trusted — and heard that what he saw on the West Side wasn’t happening elsewhere. He spent most of his time in a small West Side area he came to think of as ground zero: Pennsylvania and North, the Gilmor Homes, the intersection of Carey and Cumberland. At Pennsylvania and North, people were dealing drugs in the open. There were illegal dice games running 24 hours a day. Twenty-seven pharmacies and two methadone clinics had been looted during the rioting, and an old colleague of Russell’s who now ran the Baltimore DEA office had concluded that there were enough new pills on the street to keep Baltimore high for a year. (Ted Sutton was getting calls from people trying to figure out what they had. “They couldn’t pronounce ‘OxyContin,’ ” he said. Some callers wondered if it was a vitamin.)

At Pennsylvania and North, it felt as if the police had simply abandoned the intersection. Russell began to suspect that they had. “There would be times I would go hours without seeing a single police coming through,” he said. “And these were high-traffic areas. Not only that, I was made aware that there were no police coming through because people would say, ‘Colonel, you’re the only police we’ve seen here today.’ Sometimes, ‘You’re the only police we’ve seen all week.’” In the first four months of the year, Baltimore’s police had arrested a monthly average of 2,630 people. In May, that number dropped almost in half, to 1,557. The uniformed police, Commissioner Batts would later say, had “taken a knee.”

The shape of public order changed. Russell met a man who ran a West Baltimore halfway house for recovering addicts, most of them heroin abusers, and the counselor called him one day with a comically outsize problem. Streetside dealing had so flourished, the man said, that his residents had to walk past 17 separate locations where dealers were actively selling heroin just to get to the methadone clinic.

Russell went out to talk to the dealers. Would they be willing to relocate? They seemed exasperated. “‘You think we like selling drugs?’” they said to Russell. “‘You think we like being out here selling poison to our own people? That’s the only thing we have to do to survive.’ ” One of the dealers suggested the city turn to them to clean up the Inner Harbor, a tourist destination that has recently been filled with trash. “You can’t get the Inner Harbor clean?” he asked Russell. “Put us in some fricking little rowboats, and we’ll get the debris out of the water if you let us.” Russell found this remarkable. “They said, ‘No one will hire us to do anything.’”

In West Baltimore, everyone understood what was happening. At one point, Russell found himself in conversation with a Gilmor Homes drug dealer he knew as Freezer, who asked if he could send a message back to the commissioner. “‘We know they still mad at us. We pissed at them. But we need our police.’” Russell shook his head. “Now, this is a criminal element talking.”

Baltimore, in its poverty and violence, is a laboratory city, its poorest neighborhoods subject to constant social-science observation and experiment; there are data sets reaching back years that detail the number of chicken bones left discarded on select city blocks (as a measure of social disorder) and the number of men clustering outside liquor stores on weekend nights. Many of these records are maintained by a professor at Johns Hopkins named Debra Furr-Holden, and she could see the data change almost immediately. With so many stores burned or closed, simply conducting your daily business — commuting, shopping — meant you had to travel farther, often outside your neighborhood, sometimes into places you would not have considered safe. The people who had come out of their houses during the protests did not go back inside; for the first part of the summer, something like double the ordinary number of people were outside in the evenings. “Everything about daily movement changed,” Furr-Holden told me.

Much of the city seemed utterly isolated. During the evenings, groups of men from churches and charitable organizations would pass through the affected neighborhoods, seeing what they could do to help. Among them was a pastor from North Baltimore named Heber Brown III, and as he moved through the city with his small group of church volunteers he noticed that many corner stores were boarded up. Some had been burned, and others had been abandoned. “These were food deserts already, and people were starving,” he said. Brown put in a call to a black-owned farm that operated on the eastern shore of Maryland on what had been Harriet Tubman’s ancestral land. They had already been working together to bring vegetables to Brown’s church. Now he set up a food-distribution warehouse in the church’s lobby, where they divided up bags of sweet potatoes and onions and drove packages around the city. Soon Brown’s church had set up a regular farmstand farther east on North Avenue, at Aisquith, on Wednesdays at noon. “That food was a lifeline to a lot of people,” he said. It seemed to him there was a limit to what his community could expect from the outside. “Self-sufficiency for our people — that is where my mind is right now.”

Even more urgent was the need for safety. “People weren’t calling 911,” Brown said. Instead, they called his church. Parents called, worried that their children would have to pass through a phalanx of police on their way from school to the bus stop, and so Brown put together a group of men to walk the kids past the police and onto their bus. There, he worked alongside a group of Bloods who were also serving as escorts. The calls began to come regularly for mundane problems: Children were fighting on the corner or a situation was tense. Brown formed a patrol. Men from the church would canvass the neighborhoods each night from seven to ten.

One night, when a big fight broke out among teenagers along Northern Parkway a couple of miles east of his church, Brown got panicked calls asking for help: “There’s a whole lot of children fighting, and the police are on their way.” Teachers called when they noticed a large police presence outside their school and worried that their kids would need protecting. “To have teachers and principals calling us and saying the cops are here, we need your help — it really shows you what the mood was,” Brown said. What they needed from Brown was very basic: adult bodies, and the order they implied.

Part III

Every Tuesday and Thursday, all through the summer, Lieutenant Colonel Russell and his patrol toured the Western District’s ground zero with a trailer he’d borrowed from the Parks and Recreation department called the Fun Wagon. It came with basketballs, Hula-Hoops, jump ropes. He thought that if people could just see a uniformed officer playing with children, it would do a lot of good. When he first wheeled out the Fun Wagon, he found it drew out the kids, but everyone else still held back. If a police car came by, Russell would walk over and plead with the beat cop to get out and play. He’d call the Western District commander. “I’d say, ‘Just send someone over here for five minutes, it’ll do a world of good.’”

For several weeks, no one came. But by the middle of the summer there was a detectable thaw. The police seemed to return to the Western District, and to work. In July, there were nearly 2,500 arrests citywide, and in August a little more than 2,300, totals that were within the range of what the city had come to experience as normal. Russell noticed another change: Now, when he brought out the Fun Wagon, beat cops would stop when they drove past, stay for five minutes, throw a basketball around.

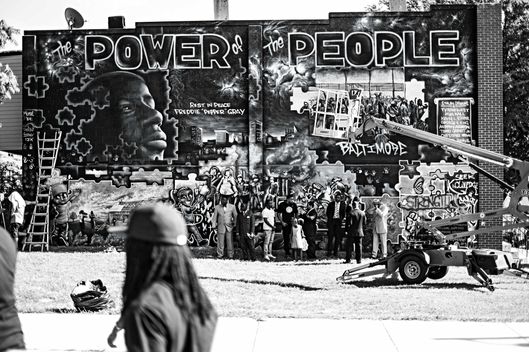

The spring had been for outrage. The summer was for activism. The NAACP opened a satellite office in Sandtown–Winchester in West Baltimore, and soon it seemed like every church and family foundation was hosting a youth summit, or extending a summer program, or holding a teach-in about the civil-rights era. The megachurch pastor Jamal Bryant was staging protests that shut down highways. Rawlings–Blake established a panel to rename monuments and streets dedicated to figures from history who had supported slavery or opposed civil rights, and momentum gathered in the City Council to reopen recreational centers in the city’s poor neighborhoods that had been closed. Rawlings-Blake’s support among voters had weakened, and the speculation was over who would challenge her from the left: perhaps the councilmember Nick Mosby, or Sheila Dixon. In July, Rawlings-Blake fired Batts as police commissioner and elevated a community-policing proponent named Kevin Davis to replace him, and the question in the Sun the next day was what had taken her so long.

Meanwhile, the events of late April were undergoing a nomenclature revision. Where first they had been called the Riots or the Protests and then — at least by some — the Uprising, now a new term emerged, almost militantly banal: the Unrest. It was employed with particular savvy by Mosby, who represents much of West Baltimore in the City Council and is married to prosecutor Marilyn Mosby, and who therefore needed to stand on all different sides of the negotiation between power and violence and safety in the city. The Unrest was euphemistic, nearly meaningless, but it had an air of willed resolution. The violence, the radicalization, the police abdication — this had all happened in a discrete point in time, now confined to the past. On September 11, Rawlings–Blake held a press conference to announce that she would not run for reelection, she made a particular point of defending her cool mien. “I don’t hear a lot about elected officials that are men talking about whether they smile

a lot,” she said.

All of the public talk in the city was about unity. The pleas to end the violence were by that point ubiquitous. But just as all of Baltimore pondered the mystery of how a progressive city could produce such a despotic police force, a second mystery had presented itself: If everyone was organized to prevent violence, why did it continue to happen? The cops were back at their posts. The whole city had been politicized. The poorest streets were filled with activist group meetings and sermons. The gangs were professing nonviolence. Still, the murders continued.

There are four neighborhoods in Baltimore in which ex–gang members are employed to interrupt street disputes before they mature into slaughter. The program, called Safe Streets, uses a protocol developed in Chicago, and its theory is that violence acts like a contagion, in cycles of revenge, and that it can be stopped before it spreads. The men who work for Safe Streets are not police, and their motives can be complicated: It is said that when a new hire starts work as a violence interrupter, an old friend of his always seems to soon be killed, and he has to endure an internal dialogue between his old ways of reacting and the new ones that he has been professing. This summer, a handgun that had been used in a shooting was found stashed in a Safe Streets office, causing a minor scandal and a temporary closure. But the program also offered another aperture into the closed network of violence in Baltimore, and so in September the Park Heights Safe Streets office hosted visitors from Johns Hopkins and the Centers for Disease Control, each inquiring about the rash of homicides.

Some theories had been suggested: Maybe the drugs stolen from the pharmacies had fueled a free-for-all. Maybe a few bad apples were to blame. Neither of these ideas had purchase among any of the violence interrupters, whose views were more systemic. They were focused not just on the men who ran the corners but the kids who sat watching, ready to come up behind. Any 8- or 9-year-old boy on a given block, said Dante Barksdale, an outreach worker at the Park Heights Safe Streets office, could tell you that block’s outlaw history: “Who used to be the big man, who was his lieutenant, who he killed, who got sent off to prison, going back to the 1980s, the 1990s.”

Murders are emotional matters, and they betray an emotional history. Often, after the violence interrupters heard that some young man was angry, once they inserted themselves physically into his path and took him out for a drink, they found that his basic trouble was not with another drug crew but with some domestic humiliation: an inability to pay the rent, or to support a child. There was an element of self-loathing. “He might be ready to take it out on someone else,” said a Safe Streets staff member named Paul Frazier. “That’s a lot of my mediations. Happens all the time.”

The kind of information that the violence interrupters seek is different from what the police usually solicit, because they are interested in crimes that have not yet happened: Who in the neighborhood was agitated, and how badly, and at whom? Who had lost hope? This meant they were especially attuned to the psychological currents that followed the protests. “This summer, during the Uprising, I saw young people more frustrated than I’ve ever seen them,” said James Timpson, Barksdale’s superior. The emotional conditions in which a distraught young man walks toward a police line crying, “Shoot me! Shoot me!” are the very same ones that would catch the notice of Timpson’s men.

Barksdale mentioned one source of tension the interrupters were working to defuse. A man had just been released from prison, where he had served more than a decade for murder, and had returned to his old neighborhood. The victim’s son, now in his early teens, had become aware that his father’s murderer was in the neighborhood and had mentioned the fact to some friends of his. One of the friends had a family connection to the paroled murderer, and so the murderer knew that the son knew that he was around.

The interrupters had met both the man and the boy. Barksdale believed that the man wanted to go straight, and the boy was a good kid, by nature given to following rules and heeding advice. Nevertheless, it had become a situation. The expectation that the boy might try to avenge his father’s death meant that both the man and the boy had reason to believe the other might try to kill him. To live in a place with a memory of violence makes it possible to be incarcerated in someone else’s past.

One idea that circulated nationally this summer was that places like these, with a history of violence, need more policing, not less. The Los Angeles Times journalist Jill Leovy’s book Ghettoside argued that these communities feel abandoned by the police because the crimes that occur within them are often left unsolved. The historian Michael Javen Fortner’s Black Silent Majority explained that the initial push for a heavier police presence in minority communities often comes from residents, who need protection. Baltimore could seem an experiment that confirms the thesis: The police pulled back, and in the void there was slaughter.

But in Baltimore, the murder rate did not drop much even after the police returned, which complicated the thesis. Russell told me that he believes 15 percent of the city’s police force are what he called “vocational,” people who see themselves as serving rather than containing their communities. Another 15 percent are problems. The remainder, seven in ten, could go either way. A neighborhood might get lucky in the cops it draws, or it might not. Many people in Baltimore, from many walks of life, told me that the city would benefit from more policing. They were not always so sure that it would benefit from more police.

Not every city starts from the same place. The homicide tallies reset each January, but the memories don’t. Baltimore was in one of the few Union states that permitted its citizens to hold slaves, the seat of the John Wilkes Booth conspiracy, the rare northern city in which housing discrimination was codified by the City Council in laws that mapped out block by block which race could live where, a place where the great cultural institutions (the Meyerhoff Symphony Hall, the Goldseker Foundation) are named after real-estate tycoons who built their fortunes in racial blockbusting. The city still has only one subway line, though six were once planned, the ambitions collapsing amid strenuous suburban opposition. Many neighborhoods, far from jobs, have withered. In Freddie Gray’s Sandtown-Winchester, about 30 percent of the houses are vacant.

The main civic action in Baltimore right now — the movements against violence by the police, the protesters, the pastors, and the interrupters — is not aimed at this legacy, because they can seem too distant to control. The present work takes place along a different plane, of mentoring and preaching and intervening. These are exercises in emotional management.

Things had accrued during the summer: not just crimes but, in their wake, grievances. All of those robberies and shootings, unresolved by the police, were causes for retaliation. “There’s a lot of beefs in Baltimore right now,” a Safe Streets worker observed. There were 27 murders in September. There were 34 in October. The pace was still one a day. As Thanksgiving approached, homicides totaled more than 300, up more than 50 percent over the previous year and the highest since 1993. Shootings had increased by 80 percent. In chronological terms, the Unrest was a blip, but it created a long line of powerful events. It came from one, too. Memory is the mood in which violence takes place. Often it is also the mechanism. To pacify a violent community is to persuade it to forget.

All through the fall, Russell kept up his vigilance. On Thursdays, he supervised training for police chaplains, a program that he had greatly expanded; he wanted neighborhood pastors and imams riding with beat cops all over the city in order to strengthen the connections between the people and the police. Russell sat in the back of a classroom while an instructor quoted Malcolm Gladwell, discussed implicit bias, and explained how well-meaning young police officers become accustomed to violence and how the tension can make them violent, too. On as many Friday evenings as he could, Russell walked the West Side. On Saturdays, he spoke at community-violence summits, and on Sundays, he preached, sometimes at his church and sometimes at others. At night, he drove back to his home in the suburbs. When Freddie Gray died, Russell had had fewer than a dozen police to work with; now he had several times as many.

Russell is more certain now than he was then that the city could be fixed and that he knows how to do it. The problem of police violence echoes the problem of street violence: Memory matters there too. “I think there’s a lot of undiagnosed trauma,” Russell told me. He recalled the first time he saw a homicide victim: “a 16-year-old kid with his head blown open, brain splattered. I looked at one officer, my partner, and he looked like he was fine. I looked at the other one, he looked like he was fine. I wasn’t fine. But because they appeared to be fine, if I wanted to be a part of this police family, I better get fine real quick. And before I could even process it, I was at my next trauma situation.” Russell continued: “We live in a city that has learned to coexist with trauma. The problem is all of us coexist with it poorly.”

Russell had grown more optimistic. The expansion of his unit and influence, and the training he presided over, suggested to him that the number of vocational cops might one day expand, that the trauma can be interrupted. “If they had let us go to the Western District from day one,” he said, “we would never have had the Freddie Gray incident.” Russell believes that the police can be taught to be conscientious. He also knows that violence moves in ways that are beyond even a conscientious cop’s control.

On the last day of August, I called Russell on his cell phone. When he picked up, he sounded strained. “It’s a very bad time,” he said. “Family emergency.” One of the colonel’s sons, Melvin Russell Jr., had been arrested and charged with stabbing a 49-year-old man earlier in the day, killing him.

It fell to Russell to tell his wife and all of their other children. Something like this had not been expected, but it was not entirely a surprise. “Schizophrenia skips a generation,” Russell said eventually. For his whole life, his own father had been a distant, introverted figure. Often, he’d worked more than one job, packing boxes or working as a janitor, and whenever he lost one he’d get another. In 1998, when he died, Russell discovered that his father had been a diagnosed schizophrenic. “Certain things started to make sense.” Russell had several sons of his own by this point. Eventually Melvin Jr. was exhibiting all the signs: pacing late at night, laughing without reason. At 19, the boy was diagnosed and went to live with a succession of relatives. Within a few years, he was hearing voices. From then on he was medicated, under the care of doctors. He “had all those advantages,” Russell said. The man Russell Jr. had killed was his roommate; they lived together in an apartment in Southwest Baltimore. The victim, Theophilus Ruffin, was the 34th and final homicide statistic in Baltimore that month.

*This article has been corrected to show that Elijah Cummings's nephew was murdered when he was attending school in Virginia.