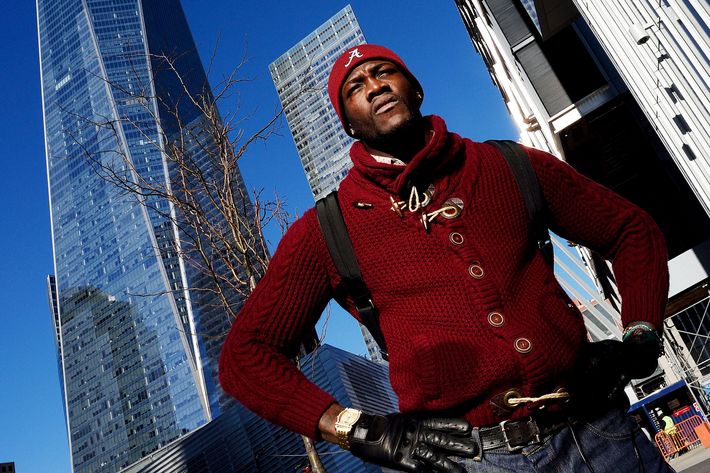

As he always does, Deontay Wilder, the 30-year-old son of a Tuscaloosa, Alabama, preacher, will say two prayers when he steps into the ring to defend his heavyweight boxing title against his Polish challenger Artur Szpilka at Barclays Center in Brooklyn on Saturday night — the first time in nearly a century the borough has hosted such a fight. (Update: Wilder defeated Szpilka in the ninth round by knockout and retained his title.)

“The first prayer is the individual prayer,” said Wilder, as he unfurled six feet and seven inches of lean muscle mass onto a cushioned chair in the airport-lounge-like VIP room of the Brooklyn Marriott. Casually attired in severely distressed designer jeans, a tan knit sweater, and a nicely turned gold pendant in the shape of a B (a reference to his nom de box, the Bronze Bomber), Wilder described “the individual prayer” as “being for safety of myself and my opponent”: “I’m a fighter. I go into the ring to break bones, spill blood, bubble your eyes, quiver your lips. But I never want to really hurt anyone. I want the other guy to go home to his family just like me.”

The second prayer, “the team prayer,” was originally centered on those who helped Wilder get ready for his fights: his manager, his trainers, his sparring partners, his Tuscaloosa walk-around guys. Now, however, the fighter says, “The team prayer is for everyone. Everyone around the world. Maybe that sounds silly, but that’s what I think a real heavyweight champion is supposed to be. The champion for everybody, someone who cares about everyone he meets like they care about him, like Muhammad Ali. You know: the guy.”

The past decade, ever since the pugilistic bellweather heavyweight division fell under the Eastern European reign of the usurping brother kings Vitali and Wladimir Klitschko, had been a difficult one for the American fight fan. Granted, the Klits possessed a portion of the master-class skills their supporters claimed for them. But the fact remained that since trainer Emanuel Steward taught the formerly stumblebumish Wladimir how to protect his glass jaw, neither Klit had been in a remotely exciting fight. They were dull, sculpted white marble, fighting even-more-dull Euros with even-more-impossible-to-spell names. The division literally fell off the map, enabling such relatively diminutive figures as Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquiao. Call it chauvinistic, call it jingoist, even call it racist if you need to, but most people who grew up watching Patterson, Liston, the nonpareil Ali, Frazier, Foreman, Iron Mike Tyson, Holyfield, along with those films of Joe Louis and Jack Johnson, have a fixed notion of who the real heavyweight champ is and what he looks like. First and foremost he is American, but even more so, he is African-American.

That’s the thing about Deontay Wilder: He’s the Great Black Hope, the newest and best chance for a return to heavyweight normalcy in years. Wilder has heard this before, of course. But even if Ali might be his all-time favorite, he’s too smart to say much about what he puts under the general heading of “politics.”

“Do I know people have been desperate to find the next great American heavyweight? I’d have to be blind not to know it,” Wilder acknowledged. “But it isn’t like there aren’t guys around who can fight. They’re playing football and basketball. That was my plan. Growing up Tuscaloosa, it comes with the territory that you want to play for the Crimson Tide. For someone like me to become a fighter these days, it almost has to be an accident.”

When a boxing PR man tries to sell you a “heartwarming angle,” you’d better start checking to see if you still have your wallet, but Wilder’s story works. As detailed in the children’s book Deontay the Future World Champ, when his daughter Naieya was born in 2005 with spina bifida, Wilder quit the local community college where he was playing football in hopes of transferring to Alabama. That dream went out the window, and he needed cash, now. He did construction work and became a waiter at the local Red Lobster. Then, thinking he might try boxing, he began sparring with a local pro.

“Maybe a few seconds in, I landed a right hand,” Wilder remembers. “Laid the man down. A couple of seconds went by, the guy lifts his head, looks up at me, and nods, like, This thing you’re doing, keep on doing it. That’s when I knew that I had this special talent for hitting people. I understood my destiny: I was going to be the heavyweight champion of the world. I went home and told my little daughter not to worry about a thing because I’d be a champ, and I would be able to take care of her forever and ever.”

It is panning out so far. With almost no amateur experience, Wilder fought his way onto the 2008 U.S. Olympic team, winning a bronze medal, the only American to get that far. As a pro, he’s undefeated in 35 fights with 34 knockouts, which, as Wilder is happy to compute, “comes out to 97.1 percent.” It doesn’t bother him that people say he’s too skinny for a heavyweight fighter at 220 pounds or when he reads on the internet that he’s mostly beaten “cab drivers” and “tomato cans.” To this Wilder counters with a Bible quote: “’Leave not to your own understanding’ … which means that people have something to say when they don’t understand how I am knocking these guys out.” Wilder defends his matchmaking as “a learning experience. That was kind of my amateur career.” He says the process paid off last January when he won his share of the championship from the dangerous Bermane Stiverne, who had been favored by many of the sport’s numerous “experts.”

The next big test, should Wilder get past Szpilka, could well be against the mammoth six-foot-nine, 250-pound Brit Tyson Fury, the “other” heavyweight champ, who recently beat the now-faded Wladimir Klitschko in a fight Wilder described as “an episode of Dancing With the Stars.” Rolling his eyes, Wilder said he took the Fury-Klitschko fight as “an insult … they’re fighting for the heavyweight championship and they are throwing two punches a round. A title fight is supposed to have drama, shows of great courage. It is supposed to be epic.”

“Fury is afraid of me,” said Wilder, who can be a motormouth once he gets going. “A lot of people can talk the talk, but they can’t walk the walk. That’s bad. But these days being able to walk the walk but not talk the talk can be bad, too,” says Wilder, who attributes some of his own verbal skills to his Holiness preacher dad. “He’s a shouter. Souls been saved in that church.”

Wilder is currently learning Spanish so once he becomes the undisputed champ he will be able to “communicate to everyone.” But he has other talking matters on his mind. Every great heavyweight champion has uttered some iconic phrase that has become “bigger than boxing,” Wilder said, citing Joe Louis’s “he can run, but he can’t hide,” Mike Tyson’s “baddest man on the planet,” and “about everything Ali ever said.” Wilder is certain he will someday soon produce a similarly celebrated elocution. “It will just come,” Wilder said, “pop out of my mouth. Can’t rush those things.”

After a while it was time for Wilder to go over to Gleason’s on Front Street, the most archetypal-looking (and -smelling) old-school boxing gym in the city, at least since they turned Cus D’Amato’s spot on 14th Street into an NYU dorm. Wilder’s opponent Artur Szpilka was there, finishing his workout. Bald-headed and sort of roundish, Szpilka didn’t look like he’d be able to put up much of a struggle against Wilder’s power, but the Pole did frustrate the champ’s trash-talk onslaught.

“His nickname is ‘the Pin.’ The best I could come up with was Pinhead from Hellraiser, like, ‘On January 16, the Pinhead is going to Hell,’” Wilder reported with consternation. “What’s a Pin anyway, some Polish thing?”

Now stripped down and showing off a rather astounding collection of abs, delts, and traps, Wilder was moving around the Gleason ring doing a little “mitt work” with his trainer, Jay Deas. His fearsome punches thudding against the mitts, Wilder went a couple of rounds before retiring to a corner and letting out a loud shriek.

“BOMB-SZQUAD!” he screamed, a reference to a series of videos touting his “Bronze Bomber” nickname. It is something Wilder does on regular intervals — without warning, at high volume — shout “Bomb Szquad!”

Asked if his “Bomb-Szquad” eruptions might qualify as primal scream therapy to spur himself on in his quest to become a great champion, Wilder said, “It might be therapeutic, but I don’t think I need it to get where I’m going. When you know something is going to happen, you just know it.”