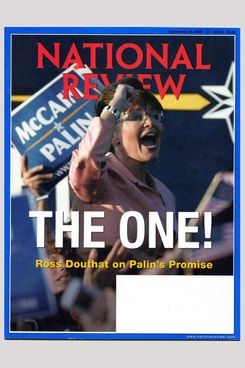

In 2008, Republican vice-presidential nominee Sarah Palin electrified conservatives in a way the more sober presidential nominee could not. People who paid close attention to Palin saw her as a dangerous buffoon. Anti-intellectualism was her driving impulse, as Noam Scheiber aptly demonstrated in a 2008 profile. She knew so little about public policy (she believed England was literally and not just symbolically ruled by a queen, she did not realize North and South Korea were separate countries, and so on) that the McCain campaign frantically scurried to conceal her ignorance, and some members of her team were actually prepared to publicly warn America against her before the election if they felt she had a chance to win. Despite those efforts, Palin’s crude ignorance shined through for anybody who cared to see it. But most conservatives (outside the McCain campaign) chose not to see it. They fervently defended Palin as an authentic populist beset by sinister liberal elites.

This week, National Review has an editorial and a cover symposium with 19 conservatives denouncing Trump as “crude,” a “boor,” “astoundingly ignorant of everything that to govern a powerful, complex, influential, and exceptional nation such as ours he would have to know,” and so on. One of the writers, Andrew McCarthy, a National Review contributing editor, expresses astonishment that Trump could not identify such figures as Hassan Nasrallah, Ayman al-Zawahiri, and Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. When Palin responded to a question about the Bush Doctrine with bug-eyed incomprehension, McCarthy angrily dismissed the suggestion that she did not know what it was as “nonsense.”

Hypocrisy is the tribute paid to virtue by vice. In the case of Donald Trump’s candidacy, the virtue is revulsion at the spectacle of a clownish reality-television star potentially claiming their party’s nomination for the presidency. National Review’s denunciation of Trump is a sign of civic health. Conservatives and liberals may not agree on policy, but some standards of public decency ought to stand apart from ideology. Conservatives may be hypocritical about this virtue, but their tribute to it reinforces its standing.

The anti-Trump conservatives are so eager to cast him out as a heretic that they refuse to acknowledge their own reflection in him. “If Trump were to become the president, the Republican nominee, or even a failed candidate with strong conservative support,” asks National Review’s editorial, “what would that say about conservatives?” The editorial treats this question as rhetorical, and moves on. It needs a real answer.

The most prominent theme in the anti-Trump symposium is that Trump is not a real conservative. Mona Charen: “Trump is no conservative—he’s simply playing one in the primaries.” Steven Hayward: “Worse, [Trump’s] inclination to understand our problems as being managerial rather than political suggests he might well set back the conservative cause if he is elected, if not make the problems of runaway executive power even worse.” Yuval Levin: “Donald Trump is no conservative.” Brent Bozell: “A real conservative walks with us … Until he decided to run for the GOP nomination a few months ago, Trump had done none of these things, perhaps because he was too distracted publicly raising money for liberals such as the Clintons; championing Planned Parenthood, tax increases, and single-payer health coverage; and demonstrating his allegiance to the Democratic party.” Katie Pavlich: “Given the high stakes both at home and abroad, America cannot afford to elect a man who is not rooted in conservatism.” NR’s editors call him “a philosophically unmoored political opportunist who would trash the broad conservative ideological consensus within the GOP in favor of a free-floating populism with strong-man overtones.”

That is all mostly correct. Trump is not a movement conservative, and people who are have good reason to doubt that he would stick with their principles if (and when) they became inconvenient. But Trump’s ability to commandeer the presidential race is no more an accident than Palin’s brief but torrid rise to the heights of right-wing idolatry. Modern American conservatism is inherently vulnerable to this kind of exploitation.

One reason for this is that, whereas liberalism tries to apply the conclusions of science and academia to public policy, conservatism rejects those conclusions in favor of an a priori belief that more government is always wrong. One contributor, the not notably hinged commentator Glenn Beck, assails Trump for supporting the stimulus, the auto bailouts, and the bank bailouts — three measures that most economists believe helped prevent a much deeper recession. Movement conservatism rejects the conclusions of wide swaths of economists, social scientists, the entire field of climate science … of course it is liable to attract anti-intellectual candidates.

A second problem is that conservative doctrine is unpopular with the public as well. The majority may often support generalized anti-government sentiment, but it does not follow those generalities through to their specific implications. During George W. Bush’s first term, the proposition that Medicare ought to add prescription-drug coverage drew the support of 90 percent of the public. Conservatives did not believe this — some of them grudgingly accepted the Bush administration’s political need to cater to popular sentiment, while others castigated Bush as a traitor to conservatism for doing so.

The habit of doublethink has embedded itself so deeply in right-wing discourse that its members hardly even notice it anymore. David McIntosh, president of the anti-tax Club for Growth, flays Trump for his advocacy of universal coverage. “About health care he has said: ‘Everybody’s got to be covered’ and ‘The government’s gonna pay for it,’” writes the disgusted anti-tax lobbyist. Of course, most Republicans have also spent the last seven years promising their own vague alternative health-care plans that will help cover the uninsured. The difference is that, when Ted Cruz or Marco Rubio promise to repeal Obamacare and replace it with something terrific, conservatives can trust that they’re lying.

This is the rub with Trump. Conservatives fear him not because he is an ignorant demagogue, but because he’s not their ignorant demagogue.