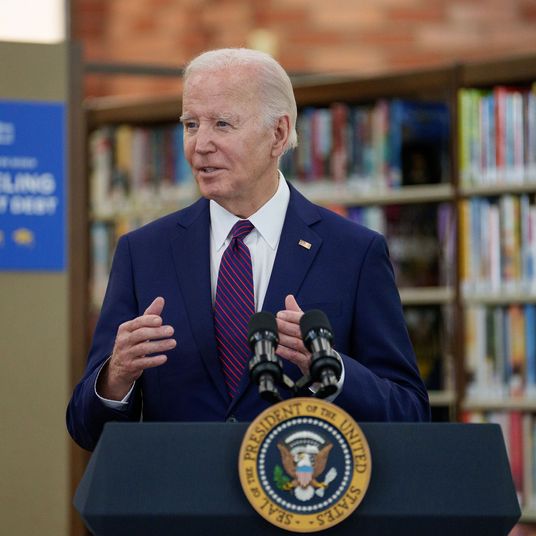

After the initial intense focus on President Obama’s determination to nominate a successor to Antonin Scalia and Senate Republicans’ determination to block him, it’s beginning to sink in that the struggle for control of the Supreme Court could be a complicated and drawn-out battle. As Juliet Eilperin and Robert Barnes of the Washington Post point out today, the next president could have more than one chance to appoint a justice, and both conservatives and liberals understand the stakes could be huge:

>The Scalia vacancy technically gives Obama the chance to establish a liberal majority on the court for the first time in decades, but even if he manages to seat a new justice in the face of blanket GOP opposition, the victory could be fleeting …

Scalia’s death at age 79 shows the peril of making predictions about the Court’s future, but the age range among the current justices would suggest that a Republican successor to Obama could have greater impact on remaking the court than a Democrat, especially if Scalia’s seat stays vacant into the next administration. Simply put, the court’s liberal bloc is older and may offer more opportunities for replacement.

When the new president is inaugurated, Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg will be almost 84. Anthony Kennedy will be 80 and Stephen Breyer, 78. Replacing Ginsburg and Breyer, both appointees of President Clinton, with conservatives would instantly shift the court’s balance for years, even if an Obama’s appointee were to replace Scalia. (The next oldest justice is Thomas, who was nominated by George H.W. Bush and will be 68 this summer.)

Many conservatives, of course, hate Kennedy, too; he was the swing vote in upholding Roe v. Wade in 1992, and played a key role in the Court’s marriage-equality decisions.

But more fundamentally, partisan polarization and gridlock in Congress have significantly elevated the importance of non-legislative entities, including the federal courts and executive-branch agencies whose power the courts might choose to expand or restrain. So control of the commanding heights of the Supreme Court is more important than ever.

What complicates the issue is the precedent set by Senate Democrats under Harry Reid in 2011 (Republicans had come close to taking the same action in 2005): the so-called “nuclear option,” removing the right to filibuster executive branch and non-SCOTUS judicial appointments. With both parties in the Senate steadily retreating from the ancient practice of deferring to the president’s choices for the High Court, and with the hot-button issues facing SCOTUS making “compromise” choices less feasible, the difference between having to muster 50 and 60 Senate votes to confirm a presidential nomination is increasingly momentous. And for that reason, if either party wins both the White House and the Senate this November, going “nuclear” on SCOTUS appointments by getting rid of the filibuster is a very high probability (and even if it doesn’t happen, the threat of “going nuclear” can and will be used to force the minority party to be reasonable).

But the converse situation is worth pondering, too. If, to cite a lively possibility, Democrats hang onto the White House while Republicans hang onto the Senate, there is no way the Senate invokes the “nuclear option.” Senate resistance to a progressive justice would likely stiffen in 2018, when Republicans will enjoy one of the most favorable Senate landscapes in memory. 25 of 33 Senate seats up that year are currently Democratic, including five in states Obama lost twice. Add in the recent GOP advantage in the kind of voters most likely to participate in midterm elections, and the ancient tendency of midterm voters to punish the party controlling the White House, and the odds of a Democratic president being able to impose her or his will on the Senate on crucial SCOTUS nominations between 2019 and 2021 is very slim.