When Henry Garrido, the executive director of the largest municipal employees union in New York City, learned a year ago what a raw deal investing in hedge funds had been for his union’s pensioners, he couldn’t restrain himself. In a fit of pique, Garrido suggested it wouldn’t be wrong for his members to conclude that “the system is rigged” after a report by the New York City comptroller concluded that the pension fund had been lining the pockets of hedge-fund managers while the retirees were getting what Garrido termed “lousy” returns.

Just five days before New Yorkers went to the polls in bitterly contested presidential primaries defined by the widespread sense among voters that Wall Street is indeed “rigged,” the New York City Employees’ Retirement System, or NYCERS, where Garrido is a trustee, voted to pull its money out of all hedge funds. That amounts to about $1.5 billion, or 3 percent, of a $50 billion pension fund.

The perception that hedge funds are a raw deal for everyone but their fee-fattened managers has not only become mainstream with astonishing speed, it has begun to pose a threat to an industry that pretty recently seemed to be on top of the world. The move by the pension for the largest municipal employees union in the U.S., representing 100,000 New Yorkers, to get out of hedge funds is the latest sign that the near $3 trillion hedge-fund industry has peaked, with global assets now slightly lower than they were in 2014, as investor redemptions hit $15 billion after last year’s poor performance. NYCERS was following the lead of another bellwether entity, the $300 billion California Public Employees Retirement System, which exited hedge funds more than a year ago.

But NYCERS pulling its money out of hedge funds is perhaps best read as the biggest victory yet for a burgeoning anti-hedge-fund movement that is fueled by widespread anger at economic inequality and argues for divestment on a wide variety of grounds — most notably right now that prominent hedge funds are squeezing Puerto Rico for debt payments, even as the island spirals deeper into economic depression. At the forefront of that protest effort is a group called Hedge Clippers. About a year ago, the American Federation of Teachers created the organization in response to anti-union efforts and other conservative political actions by various hedge-fund titans. For months the group has been lobbying public pension funds — including NYCERS — to get out of the investment vehicles. Last November, Hedge Clippers published an AFT report showing that 11 big public pension funds that have invested in hedge funds would have done better elsewhere. New York City public advocate Tish James, a NYCERS trustee, gives some credit to Hedge Clippers for the decision to divest. The group’s arguments reached “the minds of a number of individuals who want to be conscious about our public investments,” she says, and likens its efforts to the 1980s campaign to pull money out of apartheid South Africa.

Following on the heels of New York’s move, Hedge Clippers met with Ohio public-pension-fund execs to make its case, and it plans to take its battle to college campuses next, where it hopes to win over liberal-leaning universities, which have invested a huge chunk of their endowments in hedge funds, including those run by the moguls who are their alumni. “We feel confident that more pension funds are going to divest,” says Stephen Lerner, a former organizer with the Service Employees International Union and one of the key architects of Hedge Clippers.

This all comes at a time when many hedge funds have experienced their worst year since the crash of 2008, following a string of disappointing ones. Last spring, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer (also a NYCERS trustee) released the devastating report that made Garrido so angry: He found that private equity, real-estate, and hedge-fund assets had cost the city’s pension system $2.6 billion in lost value over the prior ten years, in large part due to the hefty fees they charged. Then, in 2015, NYCERS’s hedge-fund portfolio lost 1.88 percent, lagging behind both the S&P 500 and key bond indexes.

The explosive growth of hedge funds — they had one-sixth as much money under management at the turn of the century as they do today — was fueled in no small part by public pensions like NYCERS handing them huge sums of money. Those billions helped transform what previously had been a boutique investment for the Über-rich into an institutional asset class where management fees of 2 percent of the money under management and 20 percent of the investment returns created a slew of hedge-fund billionaires. Even in years their funds lost money or barely broke even, some managers earned hundreds of millions off management fees alone. Castles sprouted up on the Connecticut shore. World-class art collections were assembled. Historic fortunes were made.

Financed largely by the AFT and a few philanthropic foundations, Hedge Clippers has quickly morphed into a coalition of more than a dozen labor, civil-rights, environmental, and progressive community groups expanding to ten states and Puerto Rico with a stated mission of “unmasking the dark money schemes and strategies that the billionaire elite uses to expand their wealth, consolidate power and obscure accountability for their misdeeds.” The group’s top dozen organizers work out of the offices of their respective organizations, primarily in Washington, D.C. and New York, mobilizing through a Google listserv. The group protests a variety of issues, some more comprehensible than others: They interrupted investment conferences in New York City, alternately demanding Starboard Value’s Jeff Smith institute a $15-per-hour minimum wage for his fast-food workers at the Olive Garden and blaming Larry Robbins of Glenview Capital for causing cancer by investing in Monsanto. Still, the group knows it’s riding the zeitgeist.

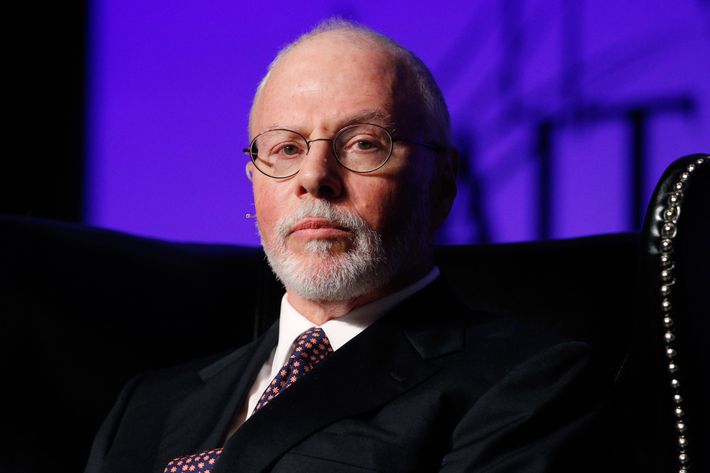

To some extent, the anti-hedge fund movement has its roots in Occupy Wall Street. Lerner, who has been a leading labor political strategist for decades and is now a fellow at Georgetown University, was also involved in that movement. He says the new, laserlike focus on hedge funds grew from seeing billionaires like GOP donors Paul Singer and Dan Loeb battle unions on public education and taxes. When Hedge Clippers shone a light on investments by billionaires Julian Robertson and Steve Cohen in drug company Gilead, which has priced a hepatitis-C-virus drug out of reach for many, that brought AIDS activists and civil-rights groups into the anti-hedge-fund cause.

In New York state, the anti-hedge-fund activists have also hooked up with a group called “Patriotic Millionaires” — which includes some hedge-fund and private-equity managers — in an effort to kill a tax break that allows these managers to pay a lower tax rate on income they earn from managing other people’s money. A bill to abolish the so-called “carried interest” loophole is currently working its way through the New York Senate.

To be sure, hedge funds aren’t going away. The biggest fund, $104 billion Westport, Connecticut–based Bridgewater Associates, which runs an opaque black-box strategy, grew 16 percent last year despite lackluster returns, according to a recent survey by data provider Hedge Fund Intelligence. Funds that are $5 billion or greater in size continue to dominate the industry, and those tend to have fee structures that allow them to survive sizeable redemptions. Moreover, the decade-long boom has made it possible for many hedge-fund billionaires to keep the doors open with just their own wealth if it comes down to that.

But the industry can’t ignore the winds of change. “The pressure on institutional investors to reduce, or abandon, their exposure to hedge funds is growing,” placing the industry at a “tipping point,” says HFI managing editor Nick Evans. Hedge funds will have to deliver results for investors that are not achievable elsewhere to justify their high fees, he says. Between 1990 and 2000, hedge funds had average annualized returns of almost 20 percent, but those days are long gone. “Out of maybe 10,000 hedge funds, only 1 percent are worth their fees on a net basis,” says Michael Hennessy, managing director of Morgan Creek Capital Management, which invests in hedge funds. “There are a lot who are not worthy and should go away.”

To survive, hedge funds will also have to confront the new political reality that has taken hold, as their politics and their investments become more closely scrutinized, thanks in no small part to Hedge Clippers. Nowhere is this clearer than in the case of NYCERS, whose divestment was partly motivated by its hedge funds’ role in the Puerto Rican debt disaster that is still unfolding. Last year, the pension fund learned that at least three of the hedge funds in its portfolio (D.E. Shaw, Brigade Capital Management, and Fir Tree Partners) were among the many that own about 30 percent of Puerto Rico’s outstanding debt. Hedge funds bought into a $3.5 billion junk bond offering in 2014 and swooped in to buy more as prices sank last year.

When Puerto Rico said it might default on its $72 billion debt last summer, Hedge Clippers hammered on the hedge fund connection and staged a protest in front of the office of one of the biggest hedge-fund owners of the debt, BlueMountain Capital. The crisis hit home for the NYCERS retirees as hedge funds pushed Puerto Rico to cut public services and lay off government workers to avoid default. Thousands of those workers are members of AFSCME (American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees) — the same union that represents NYCERS retirees.

Puerto Rico, now facing a 45 percent unemployment rate, has since devolved into a humanitarian crisis, with power outages and shuttered hospitals as the Island Commonwealth has been unable to push bankruptcy legislation or debt relief through the U.S. Congress. Instead, the bondholders have launched a massive lobbying and advertising campaign accusing Puerto Rico of profligacy and demanding it pay up. The developments nudged NYCERS toward pulling its money. “A significant number of NYCERS retirees are Puerto Rican, and if they were to know we were investing in hedge funds that had a [negative] financial impact on Puerto Rico, they would support the divesting from those hedge funds,” says Tish James.

Last November NYCERS appealed to the hedge funds to help solve the Puerto Rican crisis. When that failed, trustee Garrido — who had previously complained that hedge funds’ high fees combined with lousy returns were a “rigged system” — went on the attack at a December 3 press conference on Capitol Hill. As Latino political activists pressed Congress for help, he criticized hedge funds for profiting from the economic crisis while demanding austerity policies that hurt the island’s working class. Four months later, NYCERS voted to dump its hedge-fund investments.

“It was no longer abstract: Are the returns good or bad?” says Lerner of Hedge Clippers. “It made it more like real life — and more urgent.”