In the brouhaha over Bernie Sanders’s remarks about various aspects of Hillary Clinton’s record that indicate she is “not qualified” to be president, an important landmark was reached that could well survive the eventual walk-back of his rhetorical brinkmanship. It’s this:

“I don’t think you are qualified if you have supported virtually every disastrous trade agreement which has cost us millions of decent paying jobs,” he said to applause. “I don’t think you are qualified if you’ve supported the Panama free trade agreement, something I very strongly opposed and, which as all of you know, has allowed corporations and wealthy all over the world people to avoid paying their taxes to their countries.”

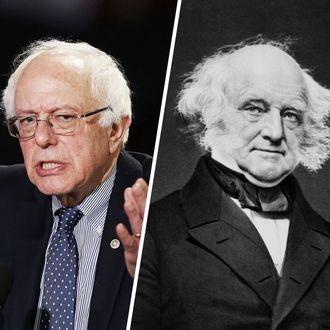

Most obviously, this anathema would apply not only to Hillary Clinton but to the 42d and 44th presidents of the United States, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. But, as a matter of fact, Sanders is seeking to become the first Democratic president since Martin Van Buren (often credited as the founder of the Democratic Party) to flatly oppose trade liberalization.

“Free trade,” which was famously popular in the agrarian South, was an important part of the glue that held together the Democratic Party before and after the Civil War. But it persisted as the default drive position of Democrats through the first half of the 20th century and arguably well beyond that. The most consistent policy view held by the great populist William Jennings Bryan throughout his long career was one in favor of free trade. Another icon of today’s ideological left, Franklin D. Roosevelt, was such a free-trader that he insisted on unilateral tariff concessions to European countries after World War II to help rebuild their economies.

John F. Kennedy launched a “round” of multilateral trade negotiations that eventually bore his name. Jimmy Carter pushed another round.

Now, it’s true that the previously near-unanimous Democratic support for trade liberalization began to fray as the 20th century grew old. The labor movement split on the subject in the early 1960s and began moving rapidly in the other direction in the 1970s. The unsuccessful Burke-Hartke legislation promoted by labor during the Nixon administration showed the way the wind was blowing: It would have created a comprehensive system for regulating and taxing both imports and overseas investment, on the principle that American workers should never have to compete with lower-wage countries. By the 1990s, a majority of House Democrats opposed Bill Clinton on both NAFTA and the rules governing a new round of multilateral trade negotiations; congressional Democrats also denied Clinton “fast-track” trade negotiating authority. By the time Al Gore ran to become Clinton’s successor, the man who had defended NAFTA in a debate with Ross Perot was emphasizing he would only support future trade agreements if they included strong core labor and environmental standards.

But, still, the tradition held: No one fundamentally rejecting trade liberalization and globalization as a good thing won a Democratic presidential nomination or the presidency. The only conspicuously anti-trade-deal pol who ran a viable presidential campaign was Dick Gephardt in 1988 and (briefly) 2004. During the 2008 primaries Barack Obama made some noises about renegotiating NAFTA, even as his chief economic adviser got caught reassuring Canadians he was just playing to the galleries.

So Bernie Sanders is fighting an awful lot of history, ancient as it may be. And it’s notable he’s not just bucking the oldest continuing policy tradition of the party he is seeking to take over; he’s arguing that a contrary position is a disqualifying betrayal of the people Democrats should be representing. And his position brooks no compromise: He’s proudly opposed and says he will continue to oppose any and all trade liberalization agreements that might be offered. He clearly embraces the old Burke-Hartke argument that global competition and, with it, the entire theory of comparative advantage are responsible for much of this country’s economic problems.

It’s fascinating that millennials, who represent Sanders’s most enthusiastic group of supporters, are, according to most public-opinion surveys, more positive about trade liberalization and globalization than previous generations. Bernie may need to do some missionary work in his own camp on the subject. But for now he’s simply angering certain living former Democratic presidents, and stirring up more than a few ghosts as well.