It is, undeniably, getting hotter: In India, temperatures recently reached 123.8 degrees and more than 2,400 people died of heat-related illnesses last year. Thailand had its longest heat wave in 65 years, and Phoenix recorded its earliest 90-degree day ever. Global temperatures are on pace to make 2016 the hottest year on record, and people in urban areas — more than half the world’s population — are going to feel the brunt of it. Of course, climate change isn’t just an city-dweller’s problem — the onslaught of droughts and superstorms and rising seas will affect everyone. But the hive of human activity in cities, from the heat-absorbing asphalt to air-conditioner exhaust, contributes to a “heat-island” effect. Cities are often up to five degrees hotter than their surrounding areas, and those temperatures are rising at twice the rate of the planet overall. Within the next century, metropolises like New York could have triple the number of days over 90 degrees. To stay cool, cities are having to transform themselves, sometimes from the ground up.

1. Create a Windy City

Stuttgart

Average Summer High: 74˚

90˚-Plus Days in 2015: 15

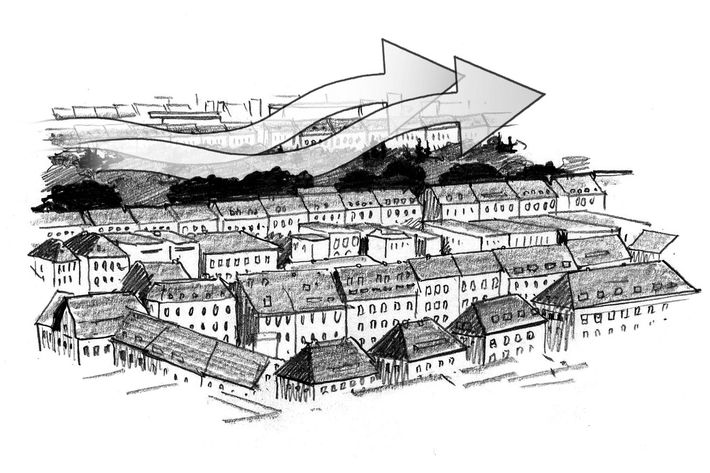

Take a city that sits in a valley basin where heat and smog get trapped, add to it more than a century as a hub of the German automotive industry, and you get a place that’s doubly screwed when it comes to heat and pollution. As far back as the 1930s, city planners have combated that one-two punch with zoning measures that create green ventilation corridors, open paths that allow natural wind patterns to flow down the valley basin, pulling cold, clean air through the city. This approach has been so effective that Beijing announced this year that it would be implementing its own version.

2. Try an Urban Spritz

Tokyo

Average Summer High: 82˚

90˚-Plus Days in 2015: 16

In Japan, uchimizu, the practice of sprinkling water on sidewalks and in gardens, dates back to the Edo period. It keeps city streets clean and cool — the water’s evaporation helps lower the surrounding air temperature. In recent years, the practice has taken on a more communal aspect with uchimizu events aimed at both lowering heat and raising awareness of global climate change. Cities around Japan have also added mist machines to supplement the traditional rite. The ones at Tokyo Station City can cool the air temperature by about five degrees.

3. Lighten the Alleyways

Chicago

Average Summer High: 82˚

90˚-Plus Days in 2015: 18

With 1,900 miles of alleys — about 2 percent of the city’s overall surface area — Chicago is, as the New York Times dubbed it, “the alley capital of America.” But these small service streets use a ton of asphalt. And this black tar absorbs the sun’s heat. So in the mid-aughts, Chicago pioneered a “Green Alleys” program, which has repaved 200 alleys with environmentally sustainable lighter concrete that reflects more of the sun’s rays. The new coating is also permeable, which allows rainwater to seep into the ground rather than becoming runoff. While less than 1 percent of Chicago’s alleys have been converted so far, this is now the default material used in alley reconstruction in the city. The program has quickly become a model for trash-strewn service streets in at least a dozen other U.S. cities, including Los Angeles and Seattle.

4. Build a Forest

Louisville

Average Summer High: 88˚

90˚-Plus Days in 2015: 38

Hailed as the fastest-warming heat island in the country, Louisville is set to embark on a series of ambitious measures to turn the tide. Atop its agenda is a proposal to plant 450,000 new trees. Tree coverage is at its worst downtown, where vegetation covers about 8 percent of the area, and temperatures can be up to 20 degrees hotter than nearby suburbs and countryside.

5. Mix and Match Your Greenery

Seattle

Average Summer High: 75˚

90˚-Plus Days in 2015: 12

Inspired by a program from Berlin, Seattle Green Factor requires certain projects to meet a minimum score in landscaping new developments, giving developers a variety of ways to hit the threshold: vegetated walls, rain gardens, green roofs. Developers get bonus points for using native plants, planting along the sidewalk, or creating food gardens. Washington, D.C., also opted for this model.

6. Canopy the Parking Lots

Austin

Average Summer High: 95˚

90˚-Plus Days in 2015: 121

Austin has been planting at least 3,600 new trees each year since 2001. The city has also put in place an ordinance that requires all new parking lots to have 50 percent canopy cover within the next 15 years. “Shade is one of the easiest things we can relate to, especially if you’re standing out in one of these parking lots in the middle of July,” says Embesi.

7. Make Your Own Wind

Masdar City, Abu Dhabi

Average Summer High in Abu Dhabi: 107˚

90˚-Plus Days in 2015: 242

For almost every metropolis on Earth, the cityscape and topography are relatively immutable. Not so for Masdar City. This desert enclave in Abu Dhabi is a ground-up testing lab for just how cool you can make a place. A model urban development largely paid for by the government, Masdar City first broke ground in 2008. Construction has been plagued by setbacks. So far only about 5 percent of the original master plan has been built, and only 300 or so students from the Masdar Institute (envisioned as the MIT of the Middle East) live there. Still, the city is truly cool. When the desert is 95 degrees, the temperature on the city’s streets can be about 68. A number of features contribute to the temperate weather, like strategically angled roofs, close-set buildings, and the crown jewel of this urban heat oasis: the nearly 150-foot-tall wind tower in the campus courtyard. This monolith funnels cooler winds from above down through Masdar’s streets, creating a constant cooling breeze so that you always feel like you have central air — even when you’re in the middle of the desert.

8. And Paint the Town White

New York City

Average Summer High: 82˚

90˚-Plus Days in 2015: 20

In Manhattan alone, there’s up to 40 square miles of rooftop space, making rooftops a huge source of untapped potential in the fight against city heat. The black asphalt on many New York roofs can reach 190 degrees on a summer day. Through the NYC CoolRoofs program, the city has helped reduce the surface temperature on 6 million square feet of scorching asphalt by using lighter-colored coating that reflects more of the sun’s rays and absorbs less heat. The city plans on keeping apace of a million square feet of new roofing each year. By one estimate, this could ultimately cool New York’s air temperature by about two degrees. And these white roofs undoubtedly help lessen the urban-heat-island effect. They have an ancillary benefit too. Because the rooftops absorb less heat, the internal temperatures of buildings can be significantly lower, cutting down air-conditioning bills and reducing carbon emissions. The city of Toronto has taken another tack: In 2010, it became the first North American city to require vegetated green roofs on new developments, resulting in more than 1.2 million additional square feet of green space. Green roofs provide more insulation during winter and prevent rainwater from becoming runoff. Widespread green roofs also could reduce the city’s overall temperature by three degrees.

…And Then There’s the Culinary Approach to Personal Heat Management

Hot tea

Many in the Middle East and North Africa swear that nothing cools you down better than drinking something hot. Science is on the hot-tea drinkers’ side. Hot drinks initially add to your body’s temperature, which causes you to sweat, and when the sweat evaporates, it cools you down. This only works if it’s not too humid out. If it is, you’ll just be raising your body temperature without the cooling effect of the evaporation.

Spicy food

Foods can produce increased circulation and what scientists call “gustatory facial sweating,” i.e., sweating on your face, which cools you down when it evaporates. According to Michael Pettid, author of Korean Cuisine: An Illustrated History, during the summer, “the qi within your body is cold, whereas the air outside is hot, so the idea of how to balance that is to eat spicy-hot foods.” The Koreans even have an expression for this, yi yeol chi yeol, which means using heat to regulate heat; in other words, fighting fire with fire.

Freshwater eels

The Japanese eat 100,000 tons of unagi, or freshwater eels, each year, but the cuisine is usually in peak demand during the dog days of summer — unagi is thought to have a restorative effect on the body when it’s been depleted by natsubate, or summer fatigue. There’s even a day, usually in late July, on the calendar where eating eel is purported to give you the biggest boost, the Midsummer Day of the Ox, often called “Eel Day.”

A Little Green Goes A Long Way

Vegetation cools cities by providing shade and helping to convert water to vapor (called evapotranspiration), thereby cooling the tree and the air around it. Green interventions can dramatically cut urban heat, especially in downtown areas that are a morass of concrete, steel, and asphalt. “Trees are our most efficient city workers,” says Michael Embesi, Austin’s Urban Forestry Division manager. “You don’t pay them, but they’re continually providing services to our citizens.”

Some Cooling Methods Have Been Around For Millennia

The Masdar Institute’s wind tower is an update on an ancient design called a malqaf, or “windcatcher.” The use of windcatchers stretches back to the days of the pharaohs in ancient Egypt, and they are ubiquitous throughout the Middle East. In Iran, they’re known as badgirs. These wind towers capture oncoming cool air, piping it through a building and pushing out the stale, hot air. Other centuries-old cooling techniques are also finding new forms, like the Indian baoli. When these enclosed wells began springing up 1,500 years ago, they were sources of drinkable water in parched regions of northern India. The cooling effect of the water’s evaporation combined with the below-ground construction, where the air is naturally cooler, meant that these stepwells were often oases from the heat. In designing the Pearl Academy’s campus in Jaipur, India, Manit Rastogi installed a contemporary take on the baoli in the heart of the institute.

Another heat-thwarting design making a comeback also hails from Indian and Islamic architecture: elaborate lattice screens known as jali cool down buildings by breaking up light while allowing air to flow through.

Why Skyscrapers Don’t Keep Us Cool

Despite their long shadows, tall buildings can make it harder for heat to escape at night. The taller and closer buildings are, the more likely waste heat will get trapped in the city and make the air temperature hotter.

*This article appears in the June 13, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.