Muhammad Ali, who died on Friday at the age of 74, was a legend inside the boxing ring (as you can see in this highlight reel of his career). But his clever, playful, and sometimes forceful oratory outside the ring was an accomplishment of almost equal weight, whether he was trash talking opponents in rhyme, or standing up for black rights, or speaking out against the Vietnam War. Below is a collection of some of Ali’s best and most insightful quotes and comments, both in video and text.

Ali’s gift for language was even apparent as early as 1960, when a young Ali — then still known as Cassius Clay — won a gold medal as an amateur at the Olympics in Rome. The always loquacious Clay, who was apparently referred to as the unofficial mayor of Olympic Village, followed his win by reciting a poem for fans and the press:

To make America the greatest is my goal

So I beat the Russian and I beat the Pole

And for the USA won the medal of gold.

The Greeks said you’re better than the Cassius of old.We like your name, we like your game.

So make Rome your home if you will.

I said I appreciate your kind hospitality,

But the USA is my country still,

‘Cause they’re waiting to welcome me in Louisville.

Later, as the Guardian notes, Ali’s genesis as an entertainer got a huge boost when he heard a professional wrestler named “Gorgeous George” promote himself in 1961:

After turning professional, Clay won six fights in six months. Then, on a Las Vegas radio show to promote his seventh contest, he met the wrestler “Gorgeous” George Wagner, whose promotional skills got audiences coming to watch. As Ali later told his biographer Thomas Hauser: “[George] started shouting: ‘If this bum beats me I’ll crawl across the ring and cut off my hair, but it’s not gonna happen because I’m the greatest fighter in the world.’ And all the time, I was saying to myself: ‘Man. I want to see this fight’ And the whole place was sold out when Gorgeous George wrestled … including me … and that’s when I decided if I talked more, there was no telling how much people would pay to see me.”

During a 1963 Talk Show appearance, Ali insisted that he actually thought in rhyme and even recited some of his poetry, including “the greatest short poem of all time” (hint: it has the word “me” in it):

Here is another one of Ali’s poems, from 1962:

Everyone knew when I stepped in town,

I was the greatest fighter around.

A lot of people called me a clown,

But I am the one who called the round.

The people came to see a great fight,

But all I did was put out the light.

Never put your money against Cassius Clay,

For you will never have a lucky day.

Ali also wrote a poem for before his career-making title fight with Sonny Liston in 1964, but Ali’s infamous “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” line became the most memorable part of Ali’s pre-fight boasting:

After that fight, which resulted in a stunning upset victory for Ali, he shouted from the ring, “I am the greatest! I am the greatest!” and told the press, “Eat your words! I shook up the world! I’m king of the world!” Later, Ali’s “I am the greatest” stylings even became a 1964 spoken word album, and here is the title track:

Following Ali’s conversion to Islam and name-change, some of his pre-fight trash talking veered onto more sensitive topics. In a television interview preceding his 1967 championship-defending fight with Ernie Terrell, Ali at first denigrating Terrell with his trademark poetry, but eventually called Terrell an “Uncle Tom” and even slapped him when he refused to call Ali by his new Muslim name:

During the subsequent fight at the Houston Astrodome, Ali had essentially rendered Terrell helpless after the eighth round, and he then famously started shouting “What’s my name!” while delivering blows on Terrell and calling him “Uncle Tom.” (See a highlight reel of that fight, which Ali won, here.) Terrell wasn’t the only boxer Ali called an “Uncle Tom,” either. Ali used the same slur, among others, in 1965 against boxing opponent Floyd Patterson, who was also a civil rights activist, but as this Sports on Earth interview gets into, it was likely just a promotional act they had agreed upon, as Ali in fact respected Patterson, who he had admired when he was a young boxer. Joe Fraizer, on the other hand, held a life-long grudge against Ali for calling him an Uncle Tom, “a dumb ugly gorilla,” and other names in the run-ups to their fights in the ‘70s. Ali would eventually say that, “Sometimes I feel a little sad because I can see how some things I said could upset some people. But I did not deliberately try to hurt anyone. The hype was part of my job, like skipping rope.”

Simple, witty rhymes were all Ali used before his legendary “Rumble in the Jungle” championship victory over George Foreman in 1974, however, when he boasted he “done handcuffed lightning, thrown thunder in jail”:

Ali gave a famous victory speech following his defeat of Foreman too, repeating his then-routine claim that he was the greatest:

Some of the Louisville Lip’s other trash talk:

- Before beating Floyd Patterson in 1965: “I’ll beat him so bad, he’ll need a shoehorn to put his hat on.”

- Before taking on heavyweight champion Sonny Liston in 1964: “I’ll hit Liston with so many punches from so many angles he’ll think he’s surrounded.”

- After beating Brian London in 1966: “You have to give him credit — he put up a good fight for one-and-a-half rounds.”

- After beating Oscar Bonavena in 1970: “I hit Bonavena so hard it jarred his kinfolks all the way back in Argentina.”

- Dissing sportscasting legend Howard Cossell before Ali’s fight with George Foreman: ”You’re always talking about, ‘Muhammad, you’re not the same man you were 10 years ago.’ Well, I talked to your wife, and she told me you’re not the same man you was two years ago!”

- Before losing to Larry Holmes in a bid to retake the heavyweight title in 1980: “I got speed and endurance. You’d better increase your insurance.”

- On boxing: “It’s just a job. Grass grows, birds fly, waves pound the sand. I beat people up.”

- On George Foreman’s boxing comeback: “Watching George come back to win the title got me all excited. Made me want to come back. But then the next morning came, and it was time to start running. I lay back in bed and said, ‘That’s okay, I’m still the Greatest.’”

- On trusting Muhammad Ali: “If Ali says a mosquito can pull a plow, don’t ask how. Hitch him up.”

Of course Ali’s oratory also contributed to his role as an activist and often controversial public figure, which began following his disillusionment with racism and his conversion to Islam, under the Nation of Islam group that had also inspired Malcolm X. Here is a collection of Ali’s comments on that shift, as well as his stance on Vietnam:

When Ali rejected the notion of fighting in the Vietnam War, he famously remarked, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong,” and that they “never called me n***ger.” (His ultimate refusal to report for service in the Army resulted in him being stripped of his heavyweight title and banned from professional boxing for more than three years.)

Here is a PBS interview from 1968 in which a very reserved Ali discusses the possibility of going to jail over his rejection of the draft, and how he saw himself, a successful black champion, as uniquely positioned to take a stand. He also gets into his — at the time — support for George Wallace and the idea of racial separation:

In another 1971 interview with the BBC’s Michael Parkinson, who has called Ali “God’s gift to the talk show host,” he showed off his skills as a storyteller, and riffed on racial differences and the white supremacy of language:

Head to the BBC for another interview with Parkinson, in which Ali explained how his “fighting is for purpose” — a notion he elaborated on in his autobiography, remarking that, “When you saw me in the boxing ring fighting, it wasn’t just so I could beat my opponent. My fighting had a purpose. I had to be successful in order to get people to listen to the things I had to say.” Ali would stand by this sentiment, never expressing any regret over his boxing careeer, for the rest of this life.

Speaking with film critic Roger Ebert in 1979, Ali also didn’t pull any punches about how he felt when Rocky defeated the black Apollo Creed — a character that was at least partially based on Ali — in Rocky II:

For the black man to come out superior would be against America’s teachings. I have been so great in boxing they had to create an image like Rocky, a white image on the screen, to counteract my image in the ring. America has to have its white images, no matter where it gets them. Jesus, Wonder Woman, Tarzan, and Rocky.

But when considering Ali’s overall personality, especially when interacting with fans, it’s worth looking at this deeply felt, somewhat bizarre, and ranging response he gave to a kid who asked him what he would do when he retired:

And then there was the time Ali prevented a suicide in 1981 after happening to be nearby when a man was threatening to jump of a Los Angeles building:

Ali didn’t always need words, either. His lighting of the Olympic torch at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, while visibly trembling as a result of his Parkinson’s disease, was considered inspirational in its own silent light:

In a 1989 Interview with Davis Miller in the Louisville Courier-Journal, Ali indicated that he believed his illness was a message from God:

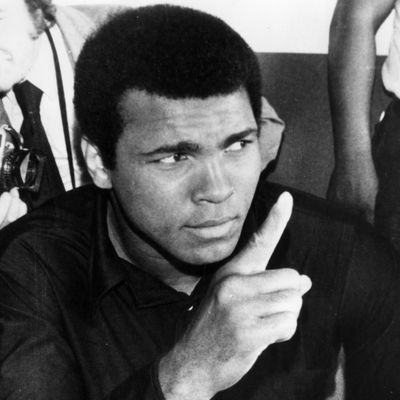

“I know why this has happened,” Ali said. “God is showing me, and showing you” — he pointed his shaking index finger at me and widened his eyes—“that I’m just a man, just like everybody else.”

And when it comes to how he wants to be remembered, there is of course a vintage Ali explanation of that too: