Donald Trump tells demonstrable lies on a near-daily basis. Few of these lies are frivolous. Many are central to the Republican nominee’s campaign. Trump’s credibility on foreign policy is founded on the false claim that he opposed the War in Iraq and intervention in Libya before either operation had been launched. His counterterrorism strategy of limiting Muslim immigration — and encouraging law enforcement to “get tough” on American Muslims through profiling and surveillance — is justified by a series of lies: that America has “no system to vet” refugees; that thousands of American Muslims celebrated in the streets of New Jersey on 9/11; that the neighbors of the San Bernardino shooters saw “bombs all over the floor” of the couple’s apartment but did not report them because they were afraid of being accused of racial profiling by the politically correct police.

Trump has buttressed his hard-line immigration policy with lies about the number of undocumented immigrants in the United States and on the prevalence of crime among such immigrants. His tax plan is premised on the lie that America is the “highest-taxed nation in the world.” His claim to the title of “law-and-order candidate” rests on the preposterous falsehood that Hillary Clinton wants to abolish the Second Amendment and then release “all the violent criminals from jail.”

Despite how prominently deliberate untruths have featured in the Republican nominee’s campaign, the New York Times has strived to avoid deploying the word lie when describing his statements. But last week, Trump told a whopper so obscene, even the Gray Lady couldn’t maintain her sense of decorum: After the mogul explained that it was actually Hillary Clinton who had started the “birther” movement — while Donald Trump had merely tried to put Crooked Hillary’s ugly speculation to rest — the paper printed “Trump Gives Up a Lie but Refuses to Repent” across its front page.

On Tuesday, the Times’ public editor, Liz Spayd, weighed in on this break from editorial norms. Spayd concluded that, in this instance, Trump’s dishonesty was egregious enough to demand that “loaded” word — but suggested that the paper shouldn’t make a habit out of accurately describing Trump’s deliberate falsehoods:

“Lie” is a loaded word, all right, a favorite of campaign operatives. You score every time you can get the media to catch your opponent in one, and it’s into the bonus round if you can get them to actually call it a “lie.”

… I think The Times should use this term rarely. Its power in political warfare has so freighted the word that its mere appearance on news pages, however factually accurate, feels partisan … as if you’re playing the referee in frivolous political disputes.

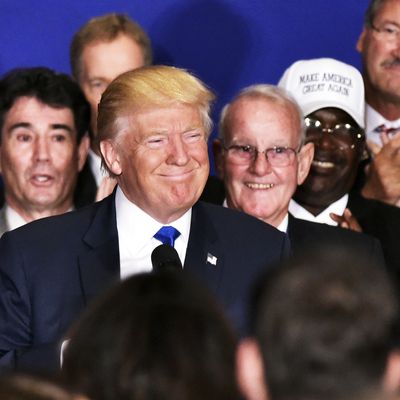

Trump’s birther moment was no frivolous dispute among sparring candidates. It was part of a five-year campaign tinged with racial overtones and dark motives. On a day when the Republican candidate backs off that claim, with a smile and a wink, I say it’s time to call a lie a lie.

Spayd wants the Times to use lie only in rare circumstances. But she also, apparently, wants the paper to describe nonfrivolous, deliberate falsities as lies.

It is impossible to meet both of these directives while covering the 2016 campaign, unless you pretend that the Republican candidate rarely spouts such falsehoods. Spayd’s use of the phrase “however factually accurate” in the passage above suggests that she may actually endorse such pretending.

Now, to be fair to Spayd, she is not suggesting that reporters refrain from highlighting Trump’s falsehoods — only that they avoid asserting that those falsehoods are intentional. And considering Trump’s fondness for conspiracy theories and his addiction to Fox News, it is sometimes difficult to establish that the mogul knows his claims are false.

What’s more, there’s no question that lie is a powerful word in political discourse. And it’s possible for a media outlet to deploy that word accurately, in a given instance, while still using the word to advance partisan ends. For example, if a news channel or magazine routinely calls out the lies of one candidate — while neglecting, intentionally or otherwise, those of another — this discrepancy can have a distorting impact on public perception. (This is the best argument against having debate moderators fact-check candidates on the fly — it is impossible to identify every false statement the candidates utter in real time, so the corrections will be inherently selective and, thus, subject to reasonable accusations of bias.)

Nonetheless, Trump has shown far too much contempt for the truth to be granted the benefit of the doubt. When confronted on his falsehoods, the GOP candidate refuses to correct them. There is no risk that highlighting his individual lies will give a false impression of his honesty, relative to that of his opponent. Yes, Hillary Clinton has told lies during her campaign and career in public life. And they should be described as such. But Trump’s mendacity is categorically different: It’s unapologetic, unrelenting, and historic in its scale. Communicating this reality to readers should overwhelm any concern for offending their sensibilities.

To identify the demonstrable lies that Trump tells in support of his agenda is not to play “the referee in frivolous political disputes.” It is to report the truth about the statements of the man running for the most powerful office on planet Earth.

The word lie is politically powerful for a reason. To deliberately mislead the public in one’s pursuit of power is to subvert the democratic process.

Newspapers shouldn’t deploy euphemisms to nudge the world into conformity with their readers’ expectations — no matter how uncomfortable accurate descriptions of our reality may be.