Health-care reform is Barack Obama’s highest-profile achievement — though I’d rank it behind his response to climate change as his most significant — and the one that is most likely to symbolize his success or failure as a president. For that reason, Republicans insisted from the outset that the law was failing: They couldn’t fix the website in time, more people would lose insurance than would gain it, medical inflation would skyrocket, and on and on. More recently, two statements have renewed their fervor. First, New York Times reporter Robert Pear published a story headlined “Ailing Obama Health Care Act May Have to Change to Survive.” And second, Bill Clinton was quoted describing the law as a “crazy system.” The right-wing news media have processed these stories as evidence that even liberals admit Obamacare is doomed.

They are evidence of nothing of the sort.

1. Clinton was not describing Obamacare as “crazy.” Jeffrey Young provides the full context of Clinton’s quote, which was a slightly mangled version of a similar riff the former president gave the same day. Clinton’s point in both appearances was that he views Obamacare as a “remarkable success,” but one that’s failed to provide help for people just out of range of qualifying for its subsidies.

2. Obamacare is a tremendous success. The law has given 20 million more Americans access to health insurance, and its cost reforms have helped keep medical inflation at historic lows. The combination of those two achievements is astounding: The federal government is spending less on health care now, after Obamacare’s coverage expansion, than it was projected to spend before Obamacare was signed into law.

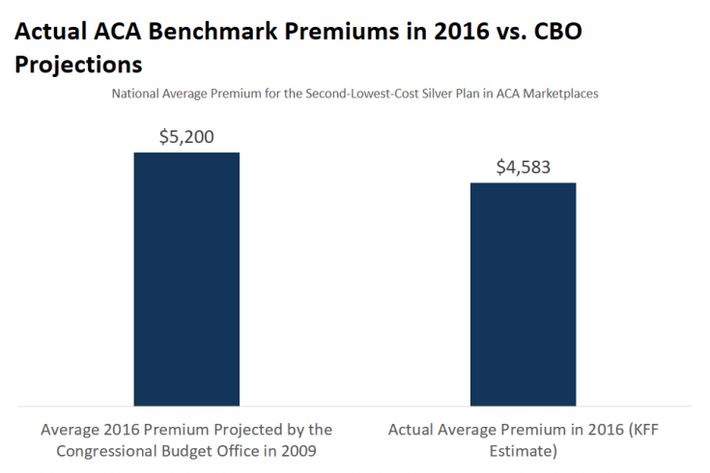

3. Premiums are still low. The law may have to change to survive, but it probably won’t. Initial premiums for the exchanges came in dramatically lower than projected, which was incredibly good news. But those premiums were too low. Many insurers discovered they couldn’t compete at such low price levels, and some of them have dropped out of the markets, which is bad. Still, even after prices are corrected, premiums remain more than $600 below their initial forecasts:

Premiums on the exchanges are also 10 percent lower than employer-sponsored insurance. The difference is that the cost of employer-sponsored insurance is hidden — we’re automatically enrolled, and the premiums are deducted from our paychecks, while the cost of enrolling in the exchanges is completely transparent. “You’ve got the full sticker price in front of you – and it can be shocking,” health-care expert Linda Blumberg told the Washington Post.

4. A “death spiral” is highly unlikely. The impact of Pear’s story leans heavily on the word may, as in the law “may” need to change in order to survive. In the fevered imaginations of the Republican mind, this possibility has been transformed into a certainty. “Young people, refusing to pay disproportionately to subsidize older and sicker patients, are not signing up,” writes Charles Krauthammer. “As the risk pool becomes increasingly unbalanced, the death spiral accelerates.”

This scenario can’t be ruled out, because the law is new and the future can’t be predicted with any certainty. But it is not the certainty excited Republicans say, and it is not even anything close to a likelihood. A death spiral occurs in a market where rising costs drive out healthy customers, leading to higher costs and the eventual exit of all but the sickest customers. This happened in a handful of states that, in the years before Obamacare, tried regulating their insurance markets to prevent price discrimination against sick customers but without providing subsidies. In those regulated but unsubsidized markets, healthy people fled, and a death spiral ensued.

That is why Obamacare put in place subsidies to make coverage affordable. With those subsidies, healthy customers with low incomes can absorb the cost of sicker customers in the risk pool because tax credits cover most or all of their premiums. And while customers might decide to start fleeing — again, the future being unpredictable — there is no evidence of any such thing happening. Indeed, Pear’s story does not describe any such death spiral occurring, and one of the experts quoted in Pear’s story tells him, “[T]he insurance market will stabilize in two or three years,” and, “We are not in a death spiral.” Yet, this very story is cited by Krauthammer as evidence that the death spiral is upon us.

5. Critics and supporters of the law are talking about different things. Republicans have always claimed that Obamacare has made the health-care system worse — that it is driving up costs or hurting more people than it is helping, or creating death panels, or is otherwise bad and should be repealed. When supporters talk about changing the law, they are not saying anything like that. They are saying that the law has made massive, historic improvements, but that more improvements would be even more beneficial.

That implied basis of comparison is critical to understand the debate about the law. The anti-Obamacare case is impossible to make, since it requires making the case that the old system, which cost more and covered fewer people, is better.

6. Fixing Obamacare is technically easy. Health-care analysts can list a bunch of changes that would make the law operate more smoothly. Many of them are very cheap. (See, for instance, here and here.) It is notable that there is huge state-by-state variation in the functioning of the law. States like California are enjoying smooth success, which is itself proof that the law can work as designed.

A new Kaiser Family Foundation study digs into the sources of this variation. It turns out that two decisions played a huge role in the success of state markets. One is Medicaid expansion — in 2012, the Republican Supreme Court, as part of a compromise in denying a legal challenge to the law, created a loophole that would allow states to refuse to expand Medicaid, which is the mechanism Obamacare uses to cover the very poor. Most Republican states have leaped at the chance to deny health-insurance coverage to their poorest citizens, and the higher costs of these low-income, uninsured citizens have bled into the exchange markets, causing premiums to rise. Simply bringing every state into the Medicaid expansion, which is already funded, would bring down premiums substantially.

A second important decision is that many states decided to grandfather in existing plans in 2014. You may remember this as the “keep your plan” dispute. Before Obamacare, the individual insurance market was based on insurers denying coverage to sick people and only selling plans to customers who had no preexisting conditions. The law always intended to regulate the market and force insurers to stop skimming off healthy people. But some of those healthy people had cheap plans — because they are currently healthy — that they wanted to keep. They raised an uproar, and the administration (unwisely) agreed to let states keep them running for another three years. That decision bought some immediate relief but has proven costly. Those healthy customers have stayed out of the exchange pool, leaving the customers in the exchange sicker than average, raising costs. Kaiser found that states that grandfathered in plans also have higher exchange costs. But, the report notes, that grandfathering ends next year, which will bring relief. And there are some administrative changes Obamacare can make and a Hillary Clinton presidency could continue. But most of the important changes require either conscious cooperation by state governments, many of which are run by hostile Republicans, or changes to federal law. That’s bad news because …

7. Improving Obamacare is politically impossible. The Republican Party’s goal on health-care reform is to destroy Obamacare. Any change that makes the law function better is one they will by definition oppose. If the Republican primary has shown us anything, it is that the party remains a dysfunctional morass of resentment whose angry impulses override any sense of public responsibility.

Even if it were possible for Republican health-care experts to negotiate changes in an atmosphere undisturbed by the kind of paranoid rage on display when tea-party activists flooded town halls in 2009 to complain about death panels, those ideas are incompatible with the law’s functioning. Republicans, and Democrats can’t compromise on health care for the same reason they can’t compromise on taxes: They have diametric goals. On taxes, Republicans want to shift the burden from the rich to the poor, while Democrats want the opposite. A similar dynamic exists in health care. Republicans want to restore the ability of healthy and wealthy people to buy cheap plans that don’t cross-subsidize the sick and the poor — the very features of the insurance system that Obamacare was designed to stop. Since Republican ideas for improving the health-care system all involve shifting costs from the rich and healthy to the poor and sick, there’s just no way to blend them together with the goals Democrats have in mind.

Obamacare could work better. So could many things government does — Medicaid, highway spending, environmental regulation, and on and on. These programs reflect the compromises necessary in a Madisonian system that happens to have a dysfunctional anti-government extremist party controlling legislative veto points. If and when Democrats gain control of both chambers of Congress along with the White House, they could very easily pass a suite of tweaks to make Obamacare work better. In the meantime, it’s still a pretty big deal.