Mike Pence spent much of his vice-presidential debate not defending his running mate, or even attacking Hillary Clinton, but instead indicting the Obama administration’s allegedly failed policies. Tim Kaine devoted scant attention to the defense, and Republicans walked away concluding that they had seen a glimpse of an alternate world in which their party’s winning course had not been diverted into the ditch by their evil clown nominee. “If you had a normal, professional, Republican politician on the stage, prosecuting conservative arguments, who actually knows what he’s talking about,” said former Republican adviser and staunch Trump critic Dan Senor, “we would actually be winning this election.” It is not only Republicans who say this; a version of this belief has sunk deeply into the conventional wisdom. (I appeared on the show where Senor said this, and he, Charlie Rose, and Mike Allen all agreed that this was a “change election” that Republicans were only failing to win because of Trump’s unique unfitness for office.)

In reality, Kaine’s lack of interest in defending Obama should not be mistaken for an inability to defend him. The president remains popular among the public — today’s CNN poll registering a 55 percent approval rating, the highest of his second term, being the latest evidence. Some conservatives have dismissed Obama’s rising popularity as a mere response to Trump, but this is wrong, too — Obama’s approval ratings also rose during the 2012 cycle. Elections seem to activate the support of disenchanted partisans. The cyclical fall-off of support among partisan voters does not indicate any real opportunity for Republicans, since those voters naturally return to the fold during an election.

The most ubiquitous piece of data to support the “change election” narrative is the very high “right track/wrong track number,” which was cited on the Charlie Rose panel and has become the favorite conservative measure of public opinion since Obama’s approval ratings hit 50 percent. But the right track/wrong track number has no predictive value of election outcomes. In the 1970s, when the public grew disenchanted with public institutions in the wake of Vietnam and Watergate, wrong-track numbers structurally rose and have stayed mostly high with few exceptions. “Wrong track” voters include large numbers of liberal Democrats who support the administration and feel frustrated the Republican Congress has blocked its proposals. As other, closer analysis has found, most Americans think their side is losing the partisan fight, which explains why so many believe the country is on the wrong track, but does not indicate any desire by frustrated liberals to hand the White House to the GOP.

The conviction that America is yearning to change parties in the White House is also undergirded by somewhat more amorphous evidence of working-class discontent — support for Trump among the white working class, generalized despair in rural and Rust Belt areas, and so on. In one of the short exchanges where Kaine defended Obama’s record, he cited 15 million new jobs, lower poverty, and rising median income. Pence focused instead on localized depressed areas. “You — honestly, senator, you can roll out the numbers and the sunny side, but I got to tell you, people in Scranton know different,” he said. “People in Fort Wayne, Indiana, know different.”

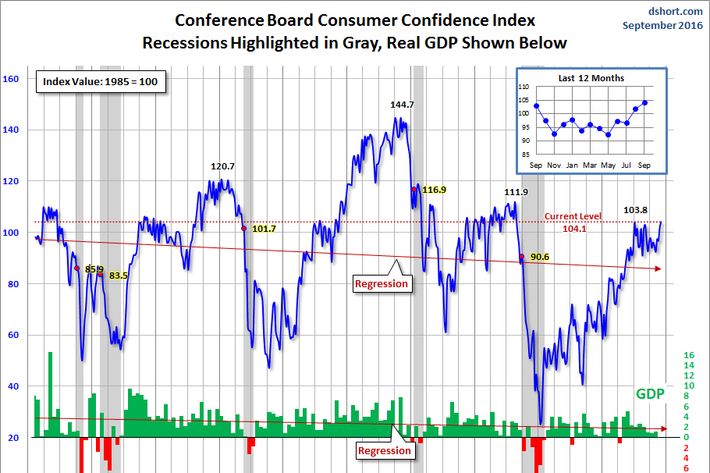

It is true that the long-term decline in manufacturing employment has had devastating impacts on communities in towns like Scranton and Fort Wayne. It is telling that Pence had to rely on localized pain in communities suffering from trends dating back decades. On the whole, American consumer confidence is strong, hitting the highest level since the recession:

It is true that the extraordinary unpopularity of the Republican nominee has made the election much harder than it could have been. But this overlooks another peculiarity of the election, which is the extraordinary unpopularity of the Democratic nominee. One can argue about why Hillary Clinton became the second-most-unpopular major-party nominee in history. (I attribute it to a combination of her and her husband’s mistakes, brutal attacks on her character and authenticity during the Democratic primary, and sexism that treats her ambitions as more unusual and contemptuous than those of male politicians.) Whatever the cause, the impact is quite real. Yes, if the Democrats had a highly unpopular nominee and the Republicans didn’t, Republicans might be winning. And yes, there are a lot of disparate feelings of unhappiness among the public, many coming from the left. But that doesn’t indicate some natural desire by the electorate to give Republicans control of government.

The “change election” myth will take on lasting power after the election. It will fuel the belief by the party Establishment that its choices were right — the maniacal opposition to everything Obama proposed, the obsession with cutting taxes for the rich, and so on — but their electoral vindication was merely derailed by the flukish nomination of a demagogue. If not for Trump, America was ready to give Republicans a chance to reverse the Obama years. The reality is that the best way to measure public approval for an elected official is to ask people if they approve of that official’s job performance. Trump has become a mechanism for Republicans to avoid coming to grips with the fact that the electorate that rebuked their party twice when it elected and reelected Obama has not reconsidered its position.