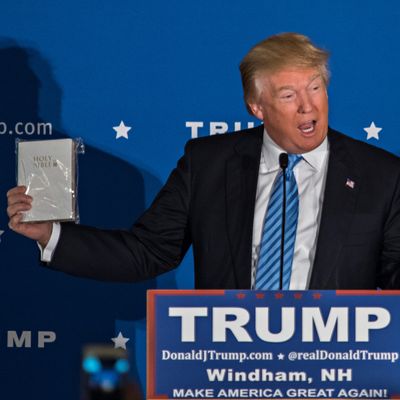

By most measurements, conservative white Evangelicals are Donald Trump’s most loyal constituency moving toward Election Day. He’s doing about as well as the Christian right’s very favorite presidential nominee, George W. Bush, was doing in this demographic in 2004, which is to say very well indeed. And at the elite level, Christian-right leaders have made an impressive display of unity and even enthusiasm for the heathenish nominee of God’s Own Party, most recently at the Values Voter Summit in Washington.

But the rationalizations Christian-right activists are muttering to themselves as they take up the crusade for Trump bespeak some very serious tensions that transcend this particular campaign, but that have been exacerbated by the Trump candidacy. Some of the faithful may buy James Dobson’s claim that Trump’s past behavior has been divinely forgiven (despite the mogul’s own claim that he needed no such thing from his close friend God) and his present behavior is best understood as reflecting a sort of pagan hangover Trump will eventually get over. Others have gone biblical and decided Trump is being used by God to knock some sense into America, much as He deployed Babylonians and Persians to keep the children of Israel in line.

And now we hear rumors of a truly disturbing rationalization circulating among Evangelical pastors in the battleground state of Pennsylvania: God is going to raise Trump to the White House in order to move that reliable Man of God Mike Pence to within a heartbeat of the presidency, at which time the new chief executive will become, um, dispensable. The lack of enthusiasm of certain progressives for Hillary Clinton certainly pales by comparison.

The Access Hollywood video of Trump boasting of the sexual fruits of celebrity and of his ability to get away with sexual assault is not making life any easier for his godly supporters. One member of Trump’s advisory “Evangelical council,” megachurch pastor James MacDonald, promptly called the man revealed by the video “lecherous and worthless,” deserving “a punch in the head from worthy men who hear him talk that way about women.” But still:

MacDonald did not abandon support for Trump outright. Instead, he said he’s putting the campaign “on notice” pending the release of another damning tape and will no longer speak out on Trump’s behalf without a “change of heart and direction.”

There are growing signs that the conflicted feelings among conservative Evangelicals are not just about Trump, but instead reflect an evolution whereby the culture-war verities of Christian nationalism are slowly giving way to a counterculture sensibility that regards fidelity to the Republican Party and even the conservative movement as a sinful temptation.

Southern Baptist spokesperson Russell Moore (who recently succeeded the conventional Christian-right leader Richard Land as head of his denomination’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission) has been the most outspoken about this change of perspective, even before Trump arrived like a barbarian warlord at the gates of ancient Rome. Moore worries that conservative Evangelicals have overidentified themselves not just with the particular political salvation tale of the GOP, but with old-school “American family values” as a sign of godliness. And unlike his many predecessors and peers who think of “real Americans” as a “moral majority” being oppressed by secular socialists, Moore thinks severing the identification of Christianity and a single country is liberating, as Emma Green explains:

The assumption that evangelicals own American culture and politics has ended. This is good for minority groups, for other Christians, and for those who are still searching. But the radicalness of Moore, who by right of inheritance should be America’s Culture Warrior in Chief, is that he thinks it’s good for evangelicals, too.

Unsurprisingly, Moore has spared no effort to denounce Donald Trump from the get-go as exemplifying the evil fruits of a sinful cohabitation between conservative Christians and the GOP. But he’s been clear in denouncing Trump’s white-identity message, not just Trump the sinner himself, saying this in a New York Times op-ed:

A vast majority of Christians, on earth and in heaven, are not white and have never spoken English. A white American Christian who disregards nativist language is in for a shock. The man on the throne in heaven is a dark-skinned, Aramaic-speaking “foreigner” who is probably not all that impressed by chants of “Make America great again.”

Moore is not alone, and in some respects the generational change reflected in his very different approach from Richard Land’s can be found in other conservative Evangelical precincts. Jon Ward interviewed another successor to a Christian-right warhorse, Focus on the Family’s Jim Daly (whose predecessor was James Dobson), who frankly discussed his difference in perspective from those who think of America as God’s country:

“All of the culture warriors — Jerry Falwell, Dr. Dobson, Pat Robertson, Chuck Colson — to my knowledge, they were all born in the late ’20s and the ’30s. And I would say, generationally, they were people that were coming out of a social structure that their belief was rather normative,” Daly said. “And when they were losing power, when they were losing that social cohesion, they panicked.”

Describing the Christian right as a by-product of cultural panic rather than religious fidelity is not something that would have ever occurred to the older generation of conservative Evangelical leaders. And so it does not occur to them — in public, anyway — to doubt the calculations that brought them to the awkward position of supporting Donald Trump, a man who, aside from his crudeness and prejudice and history of sexual immorality, clearly and openly worships the golden calf of worldly success.

The intergenerational tensions among conservative Evangelicals likely won’t matter at all on November 8. But down the road, the experience of sacrificing their integrity for a failed presidential campaign may have an impact on Christian conservative leaders who haven’t already traded their birthright of independence for a mess of Republican Party pottage. As it happens, America’s largest conservative Evangelical faith community, the Southern Baptist Convention, is home both to Russell Moore and to Jerry Falwell Jr., heir to the “moral majority” mantle of his late father and Trump’s earliest and most stolid clerical supporter. The two men represent very different paths ahead for the people in the pews they represent.

Hostile liberals and uncomprehending secular media have been predicting the demise of the Christian right for decades now. It is far too early to interpret current leadership tensions as fatal to that cause. But despite the millions of votes they will soon deliver to him, Donald Trump could ultimately prove to be the death of the Christian right as we know it. And you can add that problem to the many issues Republicans and the conservative movement have to deal with when this election is over, particularly if they don’t just lose but lose badly.