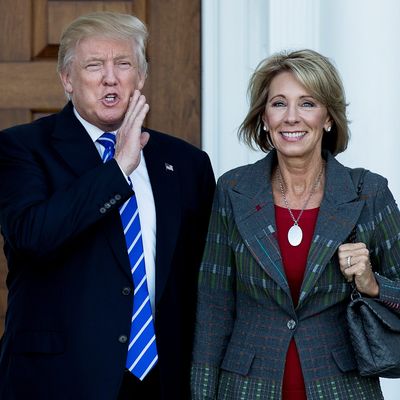

Donald Trump had two obvious, Republican-compatible ways to go in choosing a secretary of Education. He could pick someone from the world of state education policy who could comfortably supervise the elimination of any significant federal role in schools. Or he could pick a conservative ideologue who is hellbent on privatizing public education through vouchers or unaccountable charter schools that are de facto private schools.

In Betsy DeVos, Trump chose someone behind door number two. In conjunction with her husband, she has conducted a long, intense guerrilla war against what Dick DeVos calls “government schools.”

But as education wonk Kevin Carey shrewdly observes, the Department of Education is inadequate to the task of the privatization of public education:

[A]ny effort to promote vouchers from Washington will run up against the basic structures of American education.

The United States spends over $600 billion a year on public K-12 schools. Less than 9 percent of that money comes from the federal government, and it is almost exclusively dedicated to specific populations of children, most notably students with disabilities and students in low-income communities. There are no existing federal funds that can easily be turned into vouchers large enough to pay for school tuition on the open market.

Ah, but didn’t Trump himself promise some sort of big new voucher program? Yes, but there are all kinds of catches, as Carey notes:

Mr. Trump’s $20 billion proposal would be, by itself, very expensive. It may be hard to fit into a budget passed by a Republican Congress that has pledged to enact large tax cuts for corporations and citizens, expand the military and eliminate the budget deficit, all at the same time. Yet $20 billion isn’t nearly enough to finance vouchers nationwide, which is why Mr. Trump’s proposal assumes that states will kick in another $110 billion.

States don’t have that kind of money lying around. The only plausible source is existing school funding. But even if Ms. DeVos were to find a willing governor and state legislature, it’s not that easy. Roughly half of all nonfederal education funding comes from local property taxes raised by over 13,000 local school districts. They and their elected representatives will have a say, too.

If DeVos were not an ideologue, letting the states and all those local school boards do what they want, with or without new federal dollars, would be fine, particularly at a time when Republicans are doing pretty well around the country. But she’s the kind of education policy thinker who probably has no more use for state education departments or local school boards than she does for the federal agency she has been nominated to lead.

So there’s a pretty good chance she is going to be a very frustrated would-be school privatizer unless her new boss turns out to care as much about getting rid of “government schools” as she does, which is unlikely. There’s a decent chance she was chosen to begin with as a combination diversity hire and reward to the Christian Right; for the latter, she’s probably the best option short of Jerry Falwell Jr. himself, which wouldn’t have flown politically even if he wanted the gig. But the odds of Trump’s going to the mats in a highly controversial attack on public education with money and political capital borrowed from the Pentagon, tax cuts, or deporting undocumented immigrants seem vanishingly low.

DeVos’s quandary illuminates a dynamic among Republicans that goes well beyond the one issue of education policy. Most of them reflexively talk a good game about the wisdom of federalism, the value of state governments as laboratories of democracy, the superior responsiveness of levels of government closest to the people, and all that jazz. Some actually mean what they say. But many, many others care about federalism only to the extent that it is compatible with the public-policy outcomes they desire at every level of government. For certain corporate lobbyists, for example, that means letting the states determine environmental policy is a good idea only when killing environmental regulations by national fiat is not an option. In other words, for all too many conservatives, federalism is a strategy mainly to be pursued during Democratic administrations in Washington.

In the case of Donald Trump, you’d have to guess federalism is a strategy mainly to be pursued on tier-two issues where his ambitions do not extend any further than reversing Barack Obama’s policies and maybe saving some money to use on the stuff that really matters to him. And that’s probably bad news for Betsy DeVos. I give her about a year on the job.