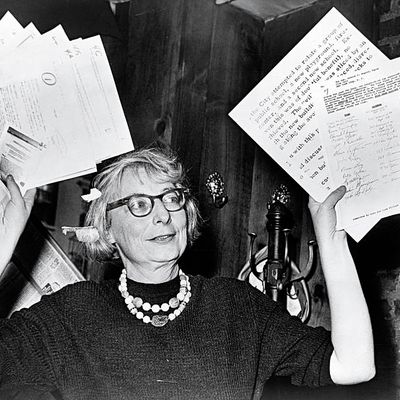

It’s Jane Jacobs time again, or maybe it always was. A century after she was born, and 55 years after she published The Death and Life of Great American Cities, the paladin of the little people still looms large on the cityscape. Robert Kanigel’s new biography, Eyes on the Street (Knopf), and a new collection of her essays, Vital Little Plans (Random House), edited by Samuel Zipp and Nathan Storring, have caused her prestige to spike. Her work was too varied and intricate to distill to a fistful of talking points, but its sensibility was coherent. She preferred the street scene to the aerial panorama, an expanse of stoops and storefronts and little routines to a great concrete machine.

In her view, planners who could read maps and balance sheets but not people would inevitably use blunt instruments to get their way, inflicting unintended misery on the very citizens they aspired to help. On the other hand, ordinary citizens left to their own devices would solve many local problems on their own and at the same time fortify their neighborhood’s character, a quality as strong and fragile as a spider’s web. Most of us now see the city the way she did, noting incremental changes that alter the topography of our lives: the hardware store that closes, the sandwich shop that opens, the tenement that makes way for a tower. Bike activists, community gardeners, and community organizers put her lessons into practice every day. So do the bureaucrats and planners she abhorred. Her influence is ubiquitous; her ideas have percolated from the radical to the self-evident.

But this outpouring of appreciation comes at a time when cities bear little resemblance to her New York. She describes the Hudson Street she lived on as a working- and middle-class diorama, where storekeepers watch the children’s comings and goings, and ladies survey the block from the windows of their low-rise apartments. The portrait of the West Village had a rosy varnish even in her day; today it feels as artificial as a brownstone block at Warner Studios. Her New York isn’t dead, mind you: “Authenticity and Innovation,” an exhibition at the Center for Architecture curated by Donald Albrecht, displays dozens of once-obsolete old buildings being recycled into offices, stores, restaurants, and manufacturing centers. A quick look around makes it clear that the rough-edged city is being repurposed as often as it is erased, and that New Yorkers know how to make use of their past. Still, it’s hard to separate Jacobs worship from nostalgia. New York’s latest boom has cultivated a wistfulness for the chaos, decrepitude, and creativity of a generation back. Though she moved to Toronto in 1968, just as New York was sliding into despond, she has become the prophet of a more authentic time.

Today we also have metropolises that spring from fishing villages, old global capitals where classes and races are sorted by a kind of economic centrifuge, hollowed-out provincial centers, megacities swamped by tsunamis of migration — varieties of urban experience that elude understanding yet demand enlightened management on a colossal scale. Cities across the planet pump out disproportionate quantities of greenhouse gases, which also gives them an outsize role to play in slowing climate change, a challenge that merges engineering and diplomacy.

For all her love of detail, her appreciation of confusion, and her close observation of the way people actually live, she was a polemical writer with a Manichean worldview and a desperate need of villains. They were not in short supply then, and they aren’t now. To her, planning was essentially corrupt, an exercise of thickheaded power by self-important men who blundered expensively into disaster. She was not wrong. Those who erected soulless housing projects and sundered neighborhoods with highways had worthy visions of millions living in harmony and efficiency, but they hewed to a simplistic model. Yet by imputing such destructive capacities to men with titles, she misunderstood the limits of their power, the social forces they were trying to wrestle with, and the good that they could do. You don’t have to be a technocrat to see that whatever goes unmanaged quickly becomes unmanageable.

She left behind an adversarial legacy, in which even relatively benign tinkering with the city unleashes a barrage of protest and a fusillade of lawsuits, which can make worthy development expensive, slow, and dumbed-down. These days, the people’s interests don’t just diverge; they collide. One person’s delightfully integrated neighborhood is another person’s erasure of ethnic pride. One activist’s affordable-housing bonanza is a preservationist’s defeat.

In this welter of conflict, often the best way to achieve a Jacobean vision is with un-Jacobean means. The Bloomberg-era transportation commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan, whose vision for the intricate life of streets closely mirrored Jacobs’s, enacted her agenda of bike lanes, revamped intersections, widened sidewalks, and public plazas with just the sort of grand-scale vision that the saint of Hudson Street deplored. Sadik-Khan’s superb book Streetfight: Handbook for an Urban Revolution documents the struggle against opponents who derive their sense of moral justice from Jacobs’s high-minded outrage.

Her natural enemies have fought to bring about — and her spiritual heirs have regularly tried to stop — change she would have applauded. She attached herself to the cause of stopping a highway through lower Manhattan, which was wonderful and wise, but also gave pure NIMBYism cover as a force of civic good. She believed that, left alone, people would naturally arrange themselves in neighborhoods that appear more disordered than they are. But few of those communities will voluntarily embrace a garbage depot or a sewage treatment plant. Jacobs valued the postindustrial West Village waterfront as an unregulated playground. In subsequent years, though, it took the combined efforts of many government agencies and mountains of tax dollars to extend waterside recreation, tamed and prettied-up, to the rest of the city. Neighborhood pluck was not enough to save cities from calamitous neglect during the 1970s. The efforts that the Koch administration launched — and that the de Blasio administration is emulating — to produce hundreds of thousands of decent, affordable apartments operated differently from the overweening and much-vilified public housing policy of a previous generation, but its aims were similar. In “The Responsibilities of Cities,” a lecture given in Amsterdam in 1984 (and included in Vital Little Plans), Jacobs advocated breaking up municipal government into neighborhood agencies, so that citizens’ groups, merchants’ associations, and so on could have more direct involvement into neighborhood change. She neglected to note that if it weren’t for centuries of top-down centralized planning at the regional and national level, Amsterdam would be an underwater metropolis.

As the world’s population packs into cities, we can no longer afford to think small, or be content with letting urban agglomerations naturally evolve into what good people make of them. A recently unearthed Pentagon video, “Megacities: Urban Future, the Emerging Complexity,” envisions armies trying to operate in anarchic quagmires, without maps, street signs, or public space. You can clear out a Tiananmen or Tahrir Square with tanks, but how do you pacify a warren of alleys and open sewers that extends for unmeasured miles? The cities of the future, the video warns, will “defy both our understanding of city planning and military doctrine.” Still, the nightmare of anarchic slums vies in the public imagination with the spontaneous emergence of plucky communities, and indeed they can coexist. The 21st century version of Jacobs’s philosophy is the glorification of “informal” urbanism. In endless shantytowns and jerrybuilt favelas, settlers don’t have the luxury of waiting for water, roads, or law. Instead, they steal electricity and rig up plastic-hose plumbing, put up cinderblock shacks, or move into structures that by rights shouldn’t really be standing. Authorities shrug; architects and academics admire the DIY techniques like biologists studying anthills.

The affluent world’s version of informal urbanism is a laissez-faire approach to private development. Jacobs had no use for large plans and little problem with builders who worked over the city block by block. Today, when New York is gripped by an epochal construction boom, when cranes descend on neighborhoods in flocks, and unused land has largely disappeared, her faith in gradual, harmless infill seems misplaced. Joan Clos, a former mayor of Barcelona who is now formulating the U.N.’s long-range urban strategy, sees that hands-off attitude as a form of destructive surrender. “The problem with city management in the last 20 or 30 years is the assumption that the market will automatically address the question of planning and design,” Clos recently told The Guardian. “As long as there’s money available, it is presumed that some kind of order will emerge spontaneously — but this is not the case.”

Perhaps the most promising way to update Death and Life is with the humanistic vision of Jonathan Rose, a do-gooder developer and urban advice-giver who stockpiles common sense in his new book The Well-Tempered City (Harper Collins). Less sweeping in his judgments or rhetorically pungent than Jacobs, Rose believes in a humanistic approach to planning. He distinguishes between complicated systems — the kind with lots of moving parts, joined in essentially predictable ways — and complex systems, in which the variables are too volatile to pin down, and the relationship between input and output is inherently murky. Cities are complex in that deeply inscrutable way. To him, that makes long-range planning both a crucial and a humble activity, based on partial information. Not knowing precisely how a changing climate threatens coastal cities doesn’t absolve them from acting. And having a vision does not obviate the need for getting local communities involved.

“Technology and data are insufficient without deeply held values, the most important of which is that we are all in it together,” Rose told me. “We need both entrepreneurism and communitarianism. In large cities you need to keep those two in balance.” He points to the plan, developed by nonprofit consortium Nos Quedamos and adopted by successive mayors, to rebuild the South Bronx after its period of desolation. Activism and administration came together in a rare partnership, lasting many years. The result is a reborn borough.

Jacobs loved cities at a time when that was an unfashionable emotion. Today, a money-fueled urban renaissance bypasses unpromising urban centers and rolls into expensive ones, often invoking her name. But while different camps squabble over her legacy in dense downtowns, a person of her contrarian disposition might find delight in suburbs these days for precisely the same reasons she loved Hudson Street: because big plans don’t take get much traction there, and because that’s where new mixtures of people are fashioning the reality they choose. With sidewalks or without.

*A version of this article appears in the October 31, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.