The Second Avenue subway, henceforth to be known as the Q line, has been planned, postponed, begun, and delayed so many times that even now, days before it opens, it still has the vagueness of a dream. If the whole project turned out to be a chimera, plenty of commuters would just shrug and say they had suspected all along. Anyone who has lived in New York for a handful of years has seen big ideas yield lots of nothing. Remember the cluster of prisms at the World Trade Center, the Olympic Village at Hunts Point, the gondola ride to Governors Island, a luminous new Penn Station — oh, wait: that last one isn’t dead yet.

For decades, it seemed that the Second Avenue subway had joined the rich catalogue of abortive plans, which form a whole parallel history of the city. Now that it’s squeaking to life, the $4.5 billion, two-mile new Q qualifies as a big deal in our age of reduced expectations, and in terms of tunnel boring-technology and street-killing nuisance, it is. But if you want to see what real vision looks like, crack open Never Built New York, by Greg Goldin and Sam Lubell, a fine chronicle of the counterfactual city that makes a good last-minute gift for fans of fantasy urbanism.

The book contains a catalogue of ambition and failure: overweening projects that someone wisely quashed, sensible ones that choked on inertia or recession, plenty of dodged bullets, and a few regrets. We can still feel relief that Robert Moses’s mid- and lower Manhattan expressways died before they could wipe away vast swaths of the Village and Murray Hill, but why couldn’t we have Rem Koolhaas’s upside-down setback tower on 23rd Street, or Santiago Calatrava’s stack of airborne boxes at 80 South Street?

All through the late-19th and early-20th centuries, far-seeing civic minds roamed the city and imagined making it bigger, faster, higher, and more advanced. They envisioned enlarging Manhattan into the harbor and filling in the Hudson River, draping bridges from skyscraper to skyscraper, and landing planes on a continuous 50-block rooftop.

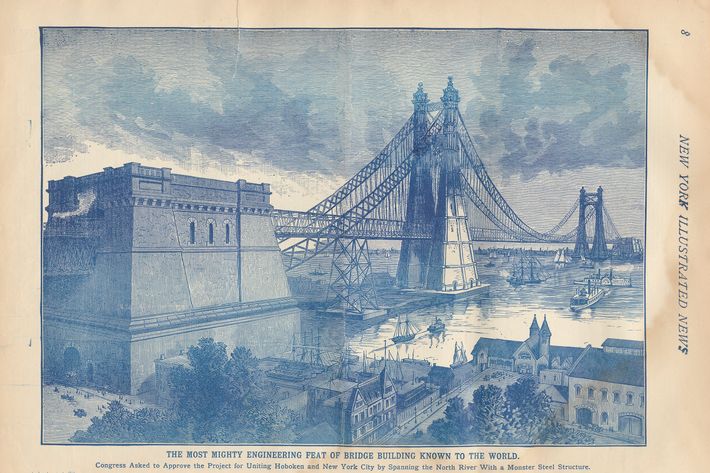

In the 1860s, the 19th-century engineer Egbert Ludovicus Viele proposed an “Arcade Under-Ground Railway” — the subway, essentially — which featured double-decker streets, with trains below, carriages above, and pedestrians on either side. The plan, which Viele promised would connect lower Manhattan to Harlem in 20 minutes, was stymied by property owners, and the idea of an underground transit system would have to wait another 40 years. Even more ambitious was Gustav Lindenthal’s 1887 plan for a North River Bridge, between Hoboken and West 23rd Street. Construction actually began on that one: Workers started erecting the immense stone piers that would have made the Egyptian pyramids seem puny.

True, as the history of the Second Avenue subway shows, it’s easy to draw pictures but hard to dig through dirt, and harder still to summon the capital and political will to put such imperial-scale schemes into practice. And sure, the vast majority of these projects were better off dead. But even so, while we’ll start taking the truncated Q line for granted in a matter of days, leafing through Never Built New York will keep right on provoking gasps at the sheer, lunatic audacity emblazoned on every page.