People forget it now, but when John Glenn lay atop an Atlas booster on February 20, 1962, there was a pretty good chance he would be blown to bits. Of the five unmanned Atlas test flights preceding his, two had exploded in the minute or so after launch. Virgil (Gus) Grissom, who flew a suborbital mission a few weeks before Glenn went up, nearly drowned when his capsule’s hatch blew open as he splashed down in the Atlantic. John Glenn was taking a genuine chance with his life.

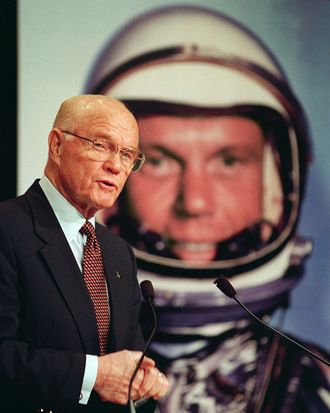

And quite a life it was that ended today, when John Herschel Glenn Jr. died, at 95, in Columbus, Ohio. Toward the beginning of his near-century on this earth (and, sometimes, beyond it), he flew combat missions in two wars — including a couple when his plane got strafed full of holes. When he signed up for the Mercury program in 1959, becoming one of the first seven astronauts, there were some sneers from test pilots, who considered it a comedown. Three years later, he was in a ticker-tape parade down Broadway, and JFK was (it was rumored) declaring him ineligible for further spaceflight because the country would not be able to handle it should Glenn be killed. In between, he had become the public face of the astronaut corps, because he was by far the most straitlaced of the seven: a non-womanizing, clean-cut man with a knack for image management who could speak authoritatively for the rest of the tight-lipped Original Seven. (He was their perfect conduit to the media: sunny as all-get-out on the surface, a combat-toughened Marine underneath.) And for his wife, Annie, who was grappling with a severe stammer; she later beat it, and became a stuttering activist, a beloved voice for those who needed one.

Space buffs know every detail of his flight: The “Godspeed, John Glenn” that Scott Carpenter radioed to him as he took off.* The “fireflies” he saw twinkling around the capsule’s window. (Aliens? No, ice crystals.). The signal, on the ground, that his capsule’s heat shield might be loose, which if true would have ensured his death on the trip home. The fact that Mission Control didn’t tell him about it until the very last moment. The high-temperature trip back through the atmosphere when he saw pieces of burning debris flying by his window. (They were chunks of the “retropack,” a bundle of rockets that Ground Control had instructed him not to jettison, in order to help keep the heat shield stayed in place.) Most of all, his schoolboy exclamations of what he saw in orbit: “Zero-G, and I feel fine!”

Or rather, his flights, plural, because NASA had a surprise in store for us all. In 1998, when NASA was going through a period of public disinterest, Glenn suggested that he fly again, aboard the Space Shuttle. He was 77 at the time, but healthy and robust, and NASA agreed to the experiment: Let’s compare the data on one test subject, with samples taken 36 years apart, and see how an elderly man handles a week-plus of weightlessness. The agency caught some flak for this, from people who said that it was more stunt than science. But let’s face it: Manned space flight is not entirely about sober experimentation. We also send up astronauts because it is incredibly cool, a billboard for the best things people can do and have done. Sending up a hero in his old age for one more trip was, from that standpoint, a fantastic idea. He got a second ticker-tape parade when he came home.

In between, he had a long if uneven career as a politician. He first ran for the senate from Ohio in 1964, and had to drop out after he fell in the tub and hit his head. Ten years and two tries later, he got in, and in 1984 he came fairly close to winning the Democratic presidential nomination, in a campaign unfortunately remembered for its monumental debts as much as for its hero candidate. He stayed in the Senate till 1999, and until today was the oldest former senator alive.

Most astronauts are anonymous now, by comparison. Even Chris Hadfield, often the best guy in your Twitter feed, isn’t the household name John Glenn was. That is, paradoxically, a great thing, because it means that scientists and doctors and engineers and physicists (and the occasional senator) are flying overhead in such numbers that we can’t keep up. But it does make their achievement a little less wondrous, a little less astounding. After the six manned Mercury missions, no American ever went into space alone again. Most likely, none ever will.

*The reference to Scott Carpenter in this paragraph has been corrected.