Liberals have spent much of the past month picking through the corpse of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign and loudly arguing about how to write up the autopsy. Most of these (amateur, political) morticians believe that the deceased had its image poisoned by the FBI, the media, and, perhaps, covert Russian agents. But there’s been a lot of disagreement about whether that poisoning (in combination with a bout of pneumonia), would have been fatal, were it not for the victim’s self-inflicted wounds.

To get more specific and less metaphorical: A lot of progressives have argued that Clinton put too little emphasis on her economic agenda and spent too little time campaigning in the Upper Midwest — and that together, these two mistakes led a bunch of white, working-class Obama voters to lift Donald Trump into the White House.

Others have disputed this narrative, arguing that it understates how much of Clinton’s rhetoric and platform focused on working-class issues, while overstating the degree to which Trump’s support derived from economic anxiety, as opposed to white racial resentment.

This week, The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson offered one of the most comprehensive versions of this rebuttal, in a column titled “The Dangerous Myth That Hillary Clinton Ignored the Working Class.” In it, he argues that liberals’ complaints about Clinton’s messaging on the economy owe more to wishful thinking than empirical evidence.

[H]ere is the troubling reality for civically minded liberals looking to justify their preferred strategies: Hillary Clinton talked about the working class, middle class jobs, and the dignity of work constantly. And she still lost.

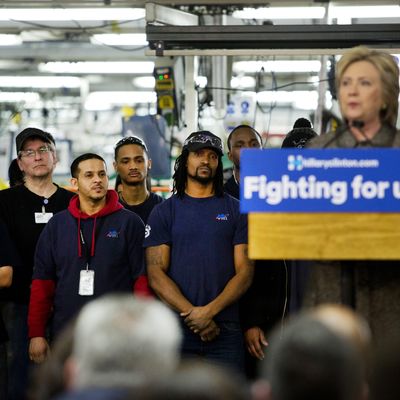

She detailed plans to help coal miners and steel workers. She had decades of ideas to help parents, particularly working moms, and their children. She had plans to help young men who were getting out of prison and old men who were getting into new careers. She talked about the dignity of manufacturing jobs, the promise of clean-energy jobs, and the Obama administration’s record of creating private-sector jobs for a record-breaking number of consecutive months. She said the word “job” more in the Democratic National Convention speech than Trump did in the RNC acceptance speech; she mentioned the word “jobs” more during the first presidential debate than Trump did. She offered the most comprehensively progressive economic platform of any presidential candidate in history—one specifically tailored to an economy powered by an educated workforce.

What’s more, the evidence that Clinton lost because of the nation’s economic disenchantment is extremely mixed. Some economists found that Trump won in counties affected by trade with China. But among the 52 percent of voters who said economics was the most important issue in the election, Clinton beat Trump by double digits.

Thompson proceeds to suggest that liberals have looked past these realities, because they point to a conclusion deeply threatening to the progressive project: “Clinton didn’t lose because the white working class failed to hear her message, but precisely because they did hear it.”

Which is to say: As the nation becomes more diverse, the white working class is becoming more chauvinistic in its attitude toward social welfare — they “support the mommy state, but only so long as it’s mothering them.” Thus, the Democrats will make few inroads by amplifying the populism of their economic policies and messaging: So long as the party is associated with diversity and anti-racism, such appeals will fall on deaf (and/or racist) ears.

Thompson’s piece makes some worthy points. The idea that white support for redistributive fiscal policies will decline as America becomes more racially and ethnically pluralistic is worth taking seriously. After all, the strongest welfare states in the world were established in some of the globe’s most racially homogenous countries. And some historians have argued that nativist restrictions on immigration passed in the 1920s may have been a precondition for the rise of the American welfare state over the decades that followed.

Still, Thompson’s central argument is unsatisfying for a reason highlighted in his piece’s final lines:

For liberals, pluralist social democracy is the project of the future, and any alternative falls somewhere between xenophobic and amoral. But what if the vast majority of white voters who voted for Trump aren’t interested in any version of that future, no matter who the messenger is?

The answer to this question, at least on the presidential level, is: That would be fine.

Few progressives would argue that Clinton could have won the “vast majority” of Trump voters with a sharper economic message. But she didn’t need to win the vast majority of them to take the White House — the presidential race was decided by 80,000 votes scattered across Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania.

Considering that Clinton barely campaigned or advertised in those first two states, it seems bizarre to ascribe her loss to the fact that voters there heard her economic message too well.

More critically, though, even if we stipulated that every single Trump voter is an unreachable racist, Clinton would not be absolved of failing to reach the Rust Belt’s working class.

Many pundits (including myself) put a lot of post-election emphasis on the Obama-Trump voter — the white, midwestern proletarian who backed the first African-American president, and then voted for the demagogue who tried to delegitimize him.

But while there were Obama-Trump voters — and while margins in the Midwest were tight enough to make them significant — they still played a supporting role in the drama of November 8.

Clinton did not lose Obama’s strongholds in the Midwest solely because white working-class Democrats flipped to Trump, but also because many Democrats stayed at home or voted third party. In Slate, Konstantin Kilibarda and Daria Roithmayr make this case in stark detail, by comparing the 2012 and 2016 vote totals in the Rust Belt 5 — Iowa, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin:

Compared with Republicans’ performance in 2012, the GOP in the Rust Belt 5 picked up 335,000 additional voters who earned less than $50,000 (+10.6 percent). But the Republicans’ gain in this area was nothing compared with the Democrats’ loss of 1.17 million (-21.7 percent) voters in the same income category. Likewise, Republicans picked up a measly 26,000 new voters in the $50–$100K bracket (+0.7 percent), but Democrats lost 379,000 voters in the same bracket (-11.7 percent).

Notably, Clinton’s struggles with the Midwest’s working class transcended racial lines: She received 400,000 fewer votes from black, indigenous, and other people of color in the Rust Belt 5 than Obama did in 2012. (While newly passed voter suppression measures in Ohio and Wisconsin likely contributed to this drop-off, they aren’t sufficient for explaining it: The drop-off was also observed in states like Pennsylvania, where no such measures were enacted between 2012 and 2016).

Slate’s data does not account for county-level shifts in voting patterns and thus, likely understate the significance of the white, working class, Obama-Trump voter.

Nonetheless, Clinton didn’t need to win over a single white Trump voter to take Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania. She just needed to turn out working class Democrats.

It’s possible that Clinton’s failure to do so was unrelated to her campaign messaging. But considering the size of the drop-off, the burden of proof should lie with the defense.

It’s undeniably true that Clinton put together a progressive economic platform that, if enacted, would have made a positive difference in the lives of working-class voters. And she did tout that platform in some of her most widely viewed public appearances.

But it’s also true that Clinton did not center her campaign on a single, simple economic narrative. Only 9 percent of the Democratic nominee’s appeals in paid advertisements referenced jobs or the economy — compared with 34 percent of Trump’s. And rather than tie Trump to his party’s unpopular fiscal agenda, Clinton often tried to distance her opponent from Paul Ryan and the rest of the Republican Party, in hopes of engineering a bipartisan rebuke of the demagogue. In prosecuting her case against Trump, Clinton put far more weight on his incompetence and hatefulness, than she did on the inferiority of his economic agenda relative to her own.

Even when Clinton addressed economic issues, she tended to do so in a piecemeal, technocratic way. She offered voters much more substance on economic policy than her opponent did, but far less clarity and concision. As Mike Konczal writes for Vox:

What were Clinton’s three things to benefit workers? There was policy everywhere, but none of it was clear to voters. An infrastructure deal — though would that even happen and didn’t Obama already try that?

Anyway, Trump promised to do it twice as big. After that, it wasn’t clear what was a priority. Stuff that actually would affect workers’ lives was presented in a technocratic and vague way. Clinton spoke of “short-termism” instead of bosses who would rather give money to shareholders than invest in their companies and workers. “Shadow banking” instead of “Wells Fargo was ripping you off and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau stopped it.”

Clinton still won the economic argument among voters who turned out Election Day, per exit polls. But it’s hard not to suspect that the relative lack of clarity and urgency in her economic message was one reason so many working-class Democrats decided to drive straight home after clocking out on November 8.

All of which is to say: There’s little evidence to suggest that Clinton lost the presidency because white working-class voters had a clear understanding of her excellent (but, from their perspective, disconcertingly anti-racist) economic platform; so little, one might even call that suggestion a dangerous myth.