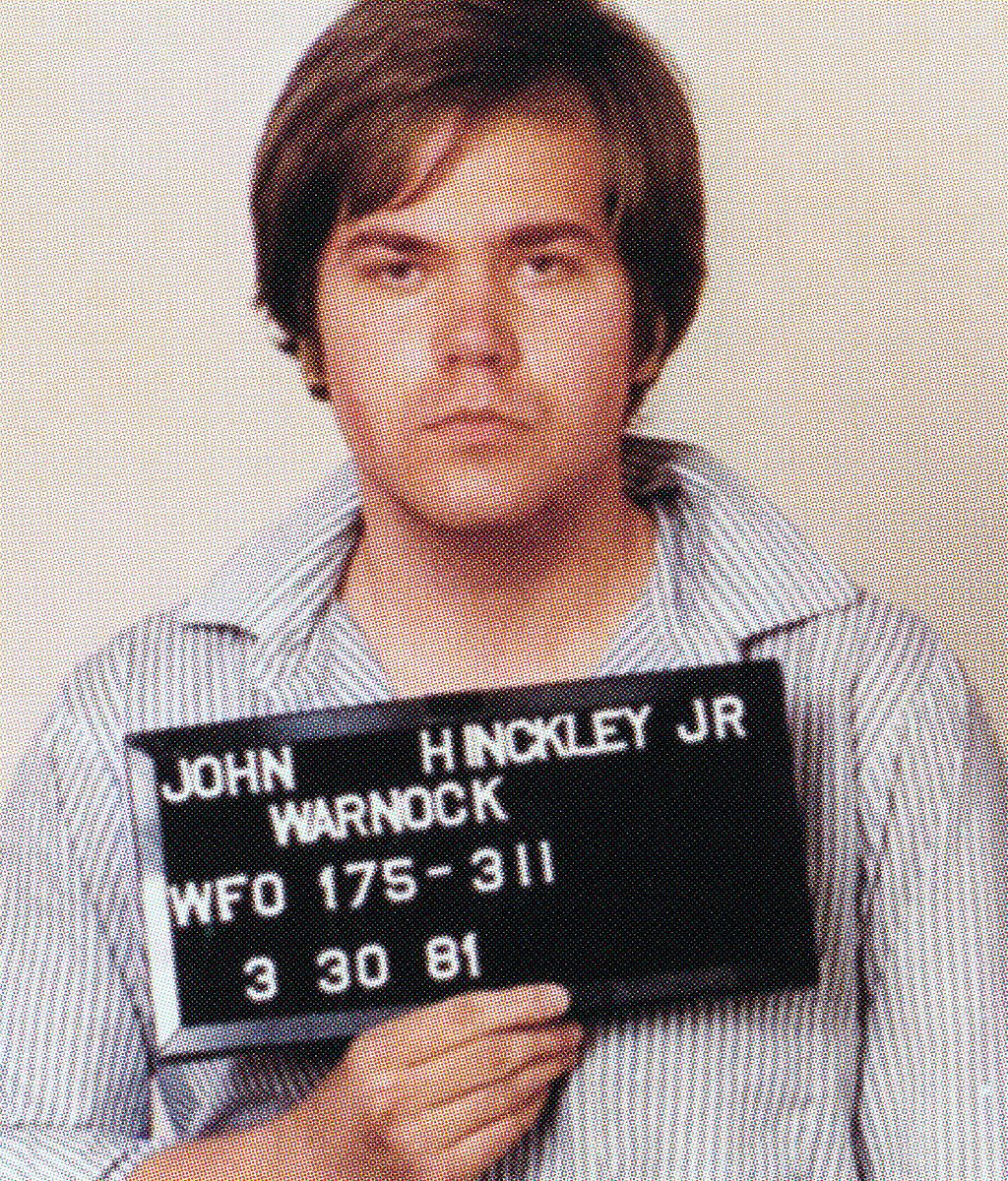

At 2:30 on Saturday afternoon, September 10, a hired SUV pulled up to the curb of a low-slung brick-and-wood house in suburban Virginia and let a passenger out. The man, who wore a tan baseball cap and a black T-shirt, did not glance at the paparazzi lenses trained on him but walked straight inside. He is far older now than in the notorious photos, but in many ways John Hinckley looks the same: blond, pudgy, nondescript. On June 21, 1982, a jury found Hinckley not guilty by reason of insanity for shooting and attempting to kill President Ronald Reagan in a display of romantic devotion to the actress Jodie Foster, who was then 19. Now, after 34 years in residence at St. Elizabeths Hospital, a public psychiatric facility in Washington, D.C., John Hinckley is home.

Hinckley is 61. He lives with his 91-year-old mother, Jo Ann, in a gated community in Williamsburg, Virginia. He sometimes suffers from constipation, allergies, and arthritis, according to court documents. He has long taken daily doses of Zoloft, for depression. He takes a prophylactic dose of Risperdal, a drug for psychosis, under his mother’s supervision.

Under the order of a federal judge, Hinckley has to live with his mother for at least a year. He must remain in treatment with mental-health professionals in Williamsburg, who have to be in regular touch with the doctors at St. Elizabeths and the court. He may not travel more than 50 miles from home, and he may not contact Foster or any of his other victims. He may not knowingly travel to places where “current or former Presidents” will be present, and if he finds himself in such locations he must leave. He may play his guitar in private, but in the interest of containing his narcissism, he may not play gigs. For now, he may browse the internet but not look at pornography or at information related to his crimes. He has to submit the make and model of his car to the Secret Service as well as his cell-phone number. He is encouraged to make friends in Williamsburg but may not invite a guest to sleep over at his house unless his mother (or one of his siblings, both of whom live in Dallas) is home. Violations of these terms could send him back to the hospital.

Kingsmill, the development in Williamsburg where Hinckley and his mother live, is a network of residential mini-villages, with theme-park names like Archer’s Mead and Padgett’s Ordinary, oriented around a championship golf course; it was built by the Anheuser-Busch company as a resort community for a certain kind of prosperous American. The residents of Kingsmill have tried to downplay concern about their infamous neighbor, but in the months leading up to Hinckley’s release, certain people said they were “not comfortable.” A retired industrial-fibers executive named Joe Mann led the opposition, protesting against the “mainstreaming of criminals” on his personal blog Mann 2 Man, as well as to the AP and the Washington Post.

Other locals vented their displeasure anonymously in The Virginia Gazette, in a write-in column called “Last Word.” “I would like to know how in the heck can they let John Hinckley be released to a 90-year-old mother,” someone wrote. “A 90-year-old person can barely take care of themselves … How can Williamsburg let him come here and stay when he shot all those people and he is crazy?”

Before the internet, stalkers had to stalk in person. In 1980, having developed an infatuation with Jodie Foster after watching Taxi Driver — in which she plays a 12-year-old prostitute — more than 15 times, Hinckley read in a magazine that Foster would be starting at Yale, and he traveled to New Haven repeatedly, leaving notes in her dorm mailbox and under her door. He even called her room, spoke to her, and recorded the conversations. In these tapes, submitted as evidence at his trial, Hinckley comes across as creepy and clueless, an indefatigable pest. The first time he reaches Foster, on September 20, he says to her, “I think you saw me today. What were you wearing?”

“I can’t remember,” she answers.

“Were you wearing a sort of, sort of green pants?”

“Um, I don’t remember,” she says.

“Greenish, greenish, greenish brown,” he says.

In their second conversation, near midnight, you can hear Foster’s roommates laughing in the background. Hinckley is pleading with Foster to stay on the line, while she endeavors to extricate herself.

“Look,” says Foster, “I really can’t talk to you, okay? But did — do me a really big favor. You understand why I can’t, you know, carry on these conversations with people I don’t know. You understand that it is dangerous, and it’s just not done, and it’s not fair and it’s rude.”

“Oh,” says Hinckley. And then: “Well, I’m not dangerous, I promise you that.”

Hinckley was 25 at the time, bespectacled, and handsome in an unremarkable way. The youngest of three children, he was raised in Dallas by exactly the kind of people who elected Reagan in a landslide: affluent, Republican, churchgoing. (The family later moved to a town outside of Denver called Evergreen.) Jack, Hinckley’s father, was an authoritarian — an oil-company chief, entirely self-made. Infuriated by his son’s passivity, Jack gave John stern lectures about stick-to-it-iveness and then exploded at each of his failures, always threatening to withhold financial support but never actually doing so. Jo Ann was more tender, the kind of homemaker who took down the chandelier at Christmastime and polished the crystal by hand. She made excuses for John each time he dropped out of school, slipping him cash from her pocketbook while he holed up in his room playing guitar. In a memoir she co-wrote with her husband, Jo Ann called John “haunted and hopeless.” John’s older brother, Scott, had gone to Vanderbilt and was Jack’s pride. Diane, his sister, had been a popular cheerleader and married young. Imposing oil portraits of Scott and Diane hung over the mantel of the family home in Colorado. There was no portrait of John.

The Hinckleys were not the kind of people who sent their children to see psychiatrists, and it wasn’t until October 1980 that they decided to consult one to help their wayward son. When they did, they found a like-minded doctor who framed John’s problem as a lack of maturity and recommended setting stricter limits. On the witness stand, Jack broke down when he recalled the tough-love ultimatum he’d given John just weeks before the shooting: Get a job or we’ll cut you off. “We forced him out at a time he just could not cope,” Jack Hinckley said. “I wish to God that I could trade places with him right now.”

The dilemma facing the jury in the summer of 1982 has dogged the Hinckley case ever since. Was Hinckley severely mentally ill, with an impaired ability to perceive reality? Or was his crime the theatrical act of a heedless, self-centered criminal? Expert psychiatric witnesses on both sides painted a consistent picture of Hinckley’s character: a hapless and privileged loser, a perpetual adolescent who nurtured grandiose fantasies of a future self, perhaps as a musician or writer, but who suffered from a paralyzing apathy, unable to keep a job or stay in school. Witness after witness called him friendless and disconnected. Also: reserved, guarded, reticent. Even Hinckley corroborated this view. In a memoir he wrote for his psychiatrist in the months before the shooting, he said, “Because I have remained so inactive and reclusive over the past five years, I have managed to remove myself from the real world.”

Beneath the flat exterior, Hinckley was a fantasist. He lied to his parents for years, telling them he was in one place when he was in another and inventing prospects that did not exist. A good amateur guitar player, Hinckley traveled to California in 1976 to try to break into the music business, telling his parents that United Artists had expressed interest. “After that, the public demand for my songs will be so incredible, I will be paid $100,000 in royalties and I can then retire to a mansion in Beverly Hills,” he wrote sardonically, in a letter home. Within two weeks, his mood had changed: “Today I went to the United Artists people and they told me quite coldly that my songs would have to be put on a waiting list. That ticks me off.” In no time, he was back home again, playing guitar in his room and stroking Titter, the family cat.

Hinckley told his family he got a job at a Dallas newspaper and also told them he was starting a business. (His “business partner” told the FBI later that he and Hinckley were mere acquaintances and that no business relationship ever existed.) In 1979, Hinckley told his parents he would not be coming home for Christmas but would spend it instead in New York City with his girlfriend, an actress named Lynn Collins, whom he had been dating on and off for several years. “The timing was particularly good,” his mother would later recall him telling her, “because his novel was finished now and this way he could make the rounds of New York publishers himself.” But Hinckley did not go to New York that Christmas. The novel did not exist. Neither did Lynn Collins. She and the dramatic romance Hinckley detailed in his letters were fabrications. Hinckley spent the holiday holed up in his rented room in Lubbock, Texas, where he was episodically attending classes at Texas Tech.

It may sound like a neat plot device, but it is impossible to overstate how much Taxi Driver influenced Hinckley in the year before he shot Reagan. In the movie, Travis Bickle — also in his 20s, friendless, unmoored — pursues a woman (played by Cybill Shepherd) far out of his league, and after she rejects him, turns his fury outward, developing a plan to assassinate Shepherd’s boss, a soulless presidential candidate. Failing in the attempt, Bickle impulsively decides to liberate the Foster character from her pimp with a murder spree: a bloodbath-catharsis, a justice fantasy, a fairy tale. Travis was down on everything, “and that’s the way I was,” Hinckley told a psychiatrist many years later. He killed a bunch of “scum balls” who were ruining her life, and “I guess I related to that.” Hinckley explained that, like Travis, he saw authority figures as “scum balls”: Taking a shot at the president was like saying, “This is for all of you out there.”

The prosecution believed it had a clear-cut case. The assassination attempt had been premeditated. Hinckley had purchased guns and exploding bullets in advance. He had gone to a shooting range to practice his aim. He even had a history of stalking presidents: On October 2 of the previous year, it turned out, he had been in Dayton scoping out President Jimmy Carter. On October 9, authorities at the Nashville airport confiscated three guns from his luggage. They booked him, then let him go.

On March 30, 1981, Hinckley looked up Reagan’s schedule, then left an operatic note to Foster in his Washington hotel room, declaring his intent and, Travis-like, offering up this murder as a martyrdom (he expected to be killed in the attempt) as well as a climactic display of love. “Jodie,” he wrote, “I’m asking you to please look into your heart and at least give me the chance, with this historic deed to gain your respect and love.” At 2:25 p.m., from within the crowd outside the Washington Hilton, Hinckley fired six bullets into the presidential entourage, hitting the president in the lung and James Brady, the press secretary, in the brain. A Secret Service man and a police officer were also wounded. News cameras captured the event and the nation watched it, repeatedly, on TV. Brady, a wheelchair user for the rest of his life, became a passionate advocate for gun control, and Reagan, who heroically walked into the ER before collapsing on the floor, saw his popularity surge.

At trial, Hinckley’s lawyers had only one move: the insanity defense. Rarely used and even more rarely successful, the insanity defense had a strategic advantage at the time: In federal court, in 1982, the burden was on the prosecution. In order to achieve its goal, which was to put Hinckley away for life, the government had to prove that he was sane when he pulled the trigger — or sane enough to “appreciate the wrongfulness of his act” (an emotional rather than cognitive standard). In the years following the Hinckley trial, those standards would be overhauled, largely in response to this verdict: “If you start thinking about even a lot of your friends, you have to say, ‘Gee, if I had to prove they were sane, I would have a really hard job,’ ” Reagan famously said. Soon, the burden in federal insanity cases shifted to the defense, and 12 states established laws permitting juries to find defendants “guilty but mentally ill.” In 1982, however, all the defense had to do was to argue convincingly that Hinckley wasn’t right in the head.

How does a jury of a dozen men and women reasonably evaluate a person’s mental status a year after the fact? The puzzle of John Hinckley had always been the same: His mild self-presentation so camouflaged his distorted thoughts that even those closest to him had no clue how dangerous he had become. The defense called four psychiatric experts, each of whom testified that Hinckley was in the throes of a delusion when he fired his gun. And then the judge permitted the Hinckley team to screen Taxi Driver to the court — a theatrical interlude in the already theatrical trial of a man who shot a movie-star president out of obsessive love for a young actress. “The line dividing Life and Art can be invisible,” wrote Hinckley in answers to questions from Newsweek before his trial. “After seeing enough hypnotizing movies and reading enough magical books, a fantasy life develops, which can either be harmless or quite dangerous.” Which raises the questions: When does a fantasy life become destructive? And whose responsibility is it to know?

In 1982, St. Elizabeths was like a horror-movie set: a dilapidated Victorian campus encircled by lawns, set amid the poorest neighborhoods of D.C. Underfunded and overcrowded, it had a long history of squalid conditions and inhumane treatment (and housed a collection of preserved brains and brain tissue spanning 100 years). Hinckley was one of 2,000 inpatients — “too many people prone to violence held in close quarters with too little supervision,” says Dr. William Carpenter, a University of Maryland psychiatrist who testified on Hinckley’s behalf at his trial. Crowd control would have been the staff’s primary concern; therapy, an afterthought. Hinckley was given a Spartan single room in the hospital’s maximum-security unit. “The water would go out for days on end,” says a former employee. “We had holes in the ceiling.” If a group was making music, say, in therapy on a floor above, “there would be times when the ceiling would start coming down on us because of the vibrations.” Throughout Hinckley’s tenure, the hospital struggled to maintain its accreditation. Almost as soon as Hinckley was admitted, his lawyers initiated the campaign to get him out. In the decades leading up to Hinckley’s arrest, patients arrested for homicide and acquitted by reason of insanity might be discharged within two years.

In every way, Hinckley was an anomaly at St. Elizabeths. For one thing, he was white, in a hospital population that was largely black. For another, he was educated. His spotty college career may have marked him as a loser in Evergreen, but at St. Elizabeths, with his love of books and music, he was professorial. His parents’ affluence and constant attention afforded him things — magazines, tailored clothes — that other patients could not procure.

Hinckley’s appearance was always blank, neutral. He “didn’t seem like a stereotypical crazy person,” says Paul Appelbaum, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia, who has written about the case. But the examiners at St. Elizabeths agreed with the trial experts: Hinckley was obsessed, full-time, with Jodie Foster. When the doctors asked what he thought about when he woke up early one morning, he said, “Jodie, Jodie, Jodie, and then there’s Jodie.” It was harder to pinpoint the root of his illness or to discern how much control he had over his behavior. His thought patterns were grandiose, homicidal, and suicidal. He was almost entirely lacking in empathy at the time, displaying instead “autistic-like thinking and serious defects in reality testing, insight and judgment.” This complex symptomology — together with his neat presentation and polite, recessive manner — made Hinckley unlike the other patients on the ward, many of whom were episodically psychotic, hallucinating, and talking to themselves. At St. Elizabeths, Hinckley was given a broad, nonspecific label: schizotypal personality, with a subset of connected and interlocking disorders, including borderline personality, depression, and narcissism. It was an imperfect diagnosis, the doctors conceded, and would likely change over time. But one thing was sure: “His defective reality testing and impaired judgment combined with this capacity for planned and impulsive behavior makes him an unpredictably dangerous person.”

In the hospital, Hinckley kept to himself, seeming only to “tolerate” other people. He was coherent. He knew where he was. He didn’t comport himself like a violent criminal, says Stuart Johnson, who had been the public defender assigned to Hinckley’s case at first. “He more or less always looked the same, like a sad sack.”

Privately, though, Hinckley was enjoying, even cultivating, his notoriety, which seemed to give him the recognition he had long craved. “The measures [federal authorities] go to in order to protect me are simply staggering,” he told Newsweek. “I feel like the president myself, with my own retinue of bodyguards. We both wear bulletproof vests now.” During his first year at St. Elizabeths, Hinckley boasted to a new patient that he was now more famous than the hospital’s previous most-famous resident, the poet Ezra Pound. In fact, as he told Penthouse in a correspondence interview in 1983, he liked to think of himself as a poet too — “a poet first and a would-be assassin last” — and attached a poem for publication. Park Dietz, the forensic psychiatrist who was the prosecution’s main expert, believes that Hinckley shot Reagan to achieve infamy rather than obscurity. “He was just a defiant, arrogant, spoiled brat who felt terrible that his siblings had been so successful and were looked at so favorably while he kept failing and earning his father’s disapproval,” Dietz said in an interview. When Hinckley made the cover of Newsweek during the trial, Dietz remembers him saying,

“I got everything I was going for — everything.”

Yet he did seem to be improving, and by 1987, Hinckley’s lawyers felt comfortable asking the judge for a 12-hour leave, so that their client might go home for Easter. His psychosis and depression were “in remission,” his doctor said, and though he sometimes still demonstrated questionable judgment, he was no longer dangerous. “He is a much different person,” his doctor told the court, adding that Hinckley could now look his doctors in the eye. But then a search of his room turned up correspondence with Ted Bundy — a condolence note of sorts, in which Hinckley expressed sorrow for the “awkward” position Bundy found himself in. Other searches around that time also uncovered dozens of pictures of Jodie Foster that Hinckley had secreted away, and a diary. “I daresay that not one psychologist knows any more about me than the average person on the street … Psychiatry is a guessing game, and I do my best to keep the fools guessing.” It would be four more years before Hinckley was allowed to walk the parklike grounds of St. Elizabeths without an escort, and 17 before he would be permitted to visit his parents, unaccompanied, overnight.

In his fantasy pursuit of Jodie Foster, Hinckley cast himself as a chivalric knight, but in life, he had never had a girlfriend. In the hospital, that changed. Hinckley became a promiscuous lover of real women, some of whom seemed to love him back — and others who did not. Leslie deVeau was already a patient at St. Elizabeths when Hinckley arrived, having murdered her 10-year-old daughter in her sleep. (She had then turned the shotgun on herself, but missed her heart and blew off her left arm.) She also was white, and from an upper-middle-class family. Hinckley approached her at a Halloween mixer. “I’d ask you to dance if I danced,” he said.

Their courtship blossomed slowly, over 20 years, constrained by stringent rules and schedules. When they could not see each other, they would exchange letters, taping them beneath the dining tables in the cafeteria. But the romance intensified when deVeau was released (in 1990) and began coming to see him during visiting hours. They would hold hands across a large table and talk, under the watchfulness of the hospital guards. deVeau needed someone to mother, she told The New Yorker in 1999. Hinckley, whom others found distant and defensive, was revealing and loquacious with her, she said. When they first started having sex, outdoors, nearly ten years after they met, it wasn’t awkward, despite Hinckley’s inexperience. “It was as if we’d both had this core of loneliness for a hundred years,” said deVeau.

But concurrently, Hinckley had another preoccupation, with the hospital’s chief pharmacist, Jeannette Wick, who later testified against Hinckley in one of his hearings. (Hinckley has “no allegiance to women,” a treating psychiatrist once said. And little understanding of romance: “He misreads cues to such an extent that ‘Hello’ to John Hinckley may mean that you are very interested in him.”) The relationship began innocuously, over a shared appreciation of the mystery writer P. D. James. Then Hinckley started showing up in Wick’s office unannounced. She would be on the phone, looking out the window with her back to the door, and when she swiveled around, she would find him sitting there. And when she told him to stop, that he had to call her office first if he wanted to see her, he started calling incessantly and hanging up whenever Wick’s secretary answered the phone. “He stares at me,” she said, according to court documents. “I guess the kids would say he stares me down. I went to the elevator, and as I went to the elevator, he re-situated himself so he could keep me in his line of vision, apparently.” (In Hinckley’s version, the feelings were mutual and he and Wick shared back rubs and played footsie.)

In 2004, deVeau and Hinckley finally broke up. When it looked like the judge might allow him to travel to Williamsburg to see his parents, deVeau didn’t want to participate in those hearings. In 2009, Hinckley looked up photos of a dental intern on the library computer and got his privileges revoked; later, he had a possibly inappropriate embrace with a woman so delusional even he conceded that it was nearly impossible to converse with her.

At St. Elizabeths, the question of sexual consent was tricky. The unofficial policy was for staff to encourage patients to process their sexual and romantic feelings in therapy. (“How else do you help patients move toward life outside of the hospital, for dating or whatever life is like?” a former employee asks.) But the question for Hinckley was yet more complicated, given how romantic distortions had once prompted him to violence, and how vulnerable the other parties were. Even his advocates in the hospital wavered on whether these “romances” were good for the objects of his affection — or for him.

Hinckley had always liked to write love songs. He had written them for Jodie Foster, and later for Leslie deVeau. And he continued to write songs for the real and imaginary women in his life, bringing them to his music-therapy sessions and recording them. He “sees himself as a protector with women who have a mental illness,” his music therapist said, “and this often comes up in his music. His music is ‘a snapshot of the hero’s journey’ where the hero meets the ideal woman and falls madly in love and wants to do anything and everything for her.”

With Cynthia Bruce, another patient at St. Elizabeths, Hinckley cast himself in a savior role. Bruce, several years younger, has severe schizophrenia and has spent her life in and out of hospitals, according to court documents. By 2009, when they became close, the judge had already approved a series of furloughs home for Hinckley — 12-hour day trips in 2003 and then three-day overnights in 2006 — and his focus was on getting released. In the hospital, he and Bruce were inseparable. And when Hinckley was in Williamsburg, to the annoyance of his mother, they talked incessantly on the phone.

But Hinckley had mixed feelings about Bruce. On the one hand, he loved her. The relationship was “pretty intense,” he told a psychiatrist, and he gave her several rings, including one that was “like the one William gave Kate,” he said. Hinckley even told his family they intended to marry, and said he was considering conversion to Catholicism because Bruce was so devout. On the other hand, he hoped to be out of the hospital soon, so “what’s the point of being engaged to her?” (“It’s very confusing, because they are either engaged or not engaged,” his psychiatrist said.) Another doctor expressed concern that Hinckley was being deceitful, leading Bruce on in order to ameliorate his loneliness. Certain people saw the relationship as evidence of his increased empathy; others saw a mind almost weaponized by selfishness. At a hospital Christmas party, Hinckley was gentlemanly when Bruce had an anxiety attack, escorting her to the front gate so she could get home. But when she’d stood outside the hospital, in full-blown psychosis, holding a sign on a pole and screaming religious terms and his name, Hinckley told his doctors he didn’t hear her.

How do doctors decide when a person’s fantasies are dangerous? In assessing patients for release, psychiatrists talk about “state or trait.” Did a person commit murder because of his “state” — hallucinations or delusions or drunkenness? Or was it depression or a mania that is a part of an underlying disorder — a “trait”? How good is the patient at understanding himself, managing his illness, and acting responsibly in his own interest?

Within three years of hospitalization, John Hinckley’s most dangerous symptoms — his obsessive, fantastical, suicidal-homicidal-romantic thoughts — had abated and, his lawyer says, without the help of psychotropic drugs. But whatever mental illness Hinckley had, it was atypical. “For some people, their symptomology doesn’t fit neatly into a category, or even two or three,” says Paul Appelbaum, the Columbia psychiatrist. “The field doesn’t have it all figured out yet. It’s not unusual to see people who have had multiple diagnoses, incompatible diagnoses, and now have a new set of diagnoses.” Eventually, the hospital settled on a durable clinical label for Hinckley’s illness: major depression and nonspecific psychosis, both of which had been in remission since at least 1990. And over time, Hinckley remained symptom-free. Generally speaking, age modulates psychosis and diminishes violent impulses.

But Hinckley would never be “a person you want to have the seat next to on a bus trip across the country,” says Carpenter, who testified at the trial that Hinckley has schizophrenia. The bedrock trait that remained, according to documents, was a third diagnostic prong. Narcissism, frequently entangled with other disorders, is a personality trait. Hinckleys examiners agreed that in his case the narcissism was “attenuated” — less virulent — but psychiatrists say it can’t be cured. The court worried about Hinckley’s tendency to withdraw. Isolation is a risk factor for recurrence in almost every mental illness, says Ken Duckworth, medical director of the National Alliance of Mental Illness. “You can’t put your finger on it and say why. Isolation is bad for symptom recurrence, for loneliness, for depression.” Even in the absence of overt psychosis, Dr. Carpenter says, Hinckley would be living with residual symptoms of his disease: “He would have difficulty engaging with other people, restricted emotionality, problems integrating emotional experience in a social context.”

The furloughs marked a turning point. From then on, freedom was at least a conceptual possibility, and Hinckley’s team scrambled to achieve that goal. Lists of “risk factors” were presented to the court. What were the conditions that led to the initial deterioration of Hinckley’s health? Isolation was one. Problems in relationships with women was another. Lack of insight was a third. In response, Hinckley’s team — his lawyers together with St. Elizabeths’ staff — set about building safeguards to mitigate those risks. They found a psychiatrist and a caseworker for him down in Williamsburg. They found things for him to do: a volunteer job at a psychiatric hospital, a gym membership. Scott and Diane, Hinckley’s brother and sister, were encouraged to travel from Dallas for the Williamsburg visits, and his parents (his father was still alive at the time) enlisted as minders. Hinckley would help his mother with chores at home — laundry, cooking, shopping, garbage. The furloughs were short at first. If he succeeded in complying with these conditions, longer durations would be considered. In the meantime, the Secret Service would routinely check in.

As evidence for Hinckley’s expanded capacity for empathy, his allies at St. Elizabeths always cited the cats. Between 20 and 50 feral cats lived on the hospital grounds, and Hinckley made it his job to care for them. He built them shelters out of scraps of wood and, on the journey back to the hospital from Williamsburg, always picked up cat food at a big-box store — 14 or 15 cases sometimes. Feeding the cats anchored Hinckley’s day: He boasted of how much the cats loved him. In his maturity, he said, he was just trying to be a regular, “sociable” guy and “good citizen,” he told the doctors. When James Brady died, in 2014, “It got me to thinking,” he said. “You know, I so diminished his life. For so many years he was in pain. He just didn’t have the life he would have had.” If he could take the shooting back, he would, Hinckley told them. “I would like to be known as something other than the would-be assassin. But that’s the image that has remained for 30 years. And although I do artwork, I do music, no one knows that,” he had said several years earlier. There’s “a negative image out there of the would-be-assassin mental patient who doesn’t do anything else, which is not true at all.”

Like hovering parents, the Williamsburg team began to force introductions within the community, hoping to connect Hinckley with someone or something that might spark his interest. He got a driver’s license so as not to overburden his mother with his care, yet it seemed he preferred for her to drive him around. Around 2009, Hinckley started taking guitar and songwriting lessons with Cabot Wade, a local musician. “His mom would drive him to the lessons, just like a middle-schooler,” remembers Wade in a phone call. He went only five or six times. “I guess his life is so complicated that it’s hard to get traction.”

Wade recalls Hinckley as affectless and ambivalent. “I don’t know how interested he was in the lessons. I know his mom is a super, super lady, and she didn’t ask for this,” Wade recalls. “The reason I said yes was because of all that she had been through. Her husband had just died, and she was all alone trying to care for this person the best she could.” Hinckley was talented enough, Wade says, and his voice had a high, reedy, Kenny Loggins–like quality, but “I don’t think he had ambitions to be a blazing guitar player.”

Each time the court considered expanding Hinckley’s freedoms, he had to submit to interviews by government psychiatrists. And in 2011, when he hoped to extend his furloughs to 17 days, he spoke at length to Dr. Raymond Patterson. He described his uneventful visits home: the bench he sat on to contemplate the James River and the little pond to which he sometimes walked for exercise. On Sundays, Hinckley remarked, he usually went to the movies. He’d recently seen Captain America.

But according to the Secret Service, who routinely followed Hinckley during his visits home, Hinckley had not seen Captain America. On September 4, at 1:13 p.m., John Hinckley arrived at the movie theater where Captain America was playing. “The subject walked to the ticket window, looked at the showtimes, but did not buy a ticket,” the Secret Service said. Instead, he walked across the street to Quiznos, bought a sandwich and a soda, and ate outdoors at the Sweet Frog yogurt shop. He talked briefly on his cell phone — twice — and looked at poetry and art magazines at Barnes & Noble. And when it was time for the movie to be over, he went back to the theater and waited out front for his mother.

Patterson confronted Hinckley about this deviation. Didn’t he feel that, given the stakes in this case, an evasion like this was significant? “It’s not that important,” Hinckley answered. “I saw a movie or I didn’t see a movie.” Hinckley went on to explain that Captain America had already started and he didn’t want to walk in the middle. “This is what I call nitpicking,” he added. “This is what happens when someone is so magnified, so scrutinized, that you’ve got to focus on something like this. Cut me a little slack.”

It was the Unitarian Universalists who finally gave Hinckley a foothold in Williamsburg. He attended a Sunday service at the church and came away unimpressed; the ministers were lesbians who didn’t talk enough about Jesus, he said. But now-board president Les Solomon invited Hinckley to join them for a weekly men’s group (“He didn’t fit in very well,” Solomon said in an interview) and eventually other members of the church agreed that reaching out to a person who met the very definition of a pariah fell in line with their calling. “We said to each other, ‘If we can’t do this kind of social-justice work, we might as well give up.’ ”

Hinckley tried to lend a hand outdoors, raking the grounds and cleaning out the fishpond. But that “wasn’t the kind of thing he was skilled at doing,” Solomon explained. Long years in the hospital had not made Hinckley very handy. Then Hinckley spoke to Solomon about his love of books, and that’s when Solomon had an idea: He would help Hinckley become an Amazon bookseller, initially through the church.

And when, last summer, federal district court Judge Paul Friedman ordered Hinckley’s “convalescent leave,” Hinckley was “ebullient,” says his lawyer, Barry Levine. “It was the culmination of an unending mission to reach a goal. He was anxious to do meaningful things.” Hinckley still works for the church, selling their books, but he also sells books through Amazon independently, using an anonymous handle and a return address that isn’t his own. The money he earns is not remotely enough to live on, but Solomon believes that Hinckley is grateful for the check.

Since he’s come home to Williamsburg for good, John Hinckley has not been in any trouble. The Secret Service is still keeping an eye on him, and locals say he’s been invisible — a recluse. Even Joe Mann, who objected the most vociferously to his presence in Kingsmill, is surprised. “I have not seen him. I have not talked to anyone who has seen him. I had some guests here the other night, and they agreed they had not heard much about him either.” The people charged with tracking Hinckley or taking note of him say they haven’t seen him either. “I haven’t heard John Hinckley’s name in months,” Peggy Bellows, editor of The Virginia Gazette, said in an interview. Bryan Hill, the county administrator for James City County, says, “No one on the local police force has seen him either. He has not been on our radar.”

Last September, just weeks after he arrived home, Hinckley quit his volunteer job at the psychiatric hospital. He has stopped making his visits to Solomon’s house. He prefers for Solomon, who is 74, to visit him. So Solomon travels regularly to Hinckley’s house to deliver books. Most of the time, Jo Ann greets him at the door together with a sweet, domesticated cat. “He has such a gracious, wonderful mother,” Solomon says. “She knows how important this bookselling is in terms of his transition.” Solomon, who is bighearted, has become convinced that it’s more advantageous for him to visit Hinckley than the other way around. If Hinckley, who works on an old PC, is having computer issues, he can help him troubleshoot. But also, the boxes of books weigh a ton, and Hinckley has a bad back. It’s just easier, Solomon says, for him to do the heavy lifting.

What will happen to Hinckley when his mother dies? Jo Ann Hinckley’s health is reportedly good, though she doesn’t golf anymore. With so many of her friends gone or in assisted living, she is grateful to have John’s company. “He is so capable,” she has remarked to psychiatrists after Hinckley’s visits home. (According to the judge’s order, Jo Ann is barred from speaking to the press, as are John and his siblings.)

Throughout John’s life, Jo Ann Hinckley has been his most constant ally. She wrote condolence notes to the families of the wounded after what she calls “the tragedy in ’81,” and she got John’s clothes tailored so that he’d have something to wear at his trial. She is “completely in awe” of her son’s efforts to get better, she has said. His relationships with women have been learning experiences: “He was what you would call a late bloomer.” He is a good driver and always gets to his appointments on time. “He is a delightful guest to have in the house,” she told a psychiatrist. “Maybe he doesn’t keep his room or the bathroom too neat, but other than that he never asks for anything extra. He knows what he needs to do.” And he plays his guitar beautifully.

His siblings have not been quite as laudatory, and they are the ones who will have to step in if their mother dies. The contingency plan is that Diane will fly up from Dallas and live with John until he can get settled somewhere else. The sale of the house in Kingsmill will help support him, but neither of them wants him back in Dallas; Scott has repeatedly mentioned the burdens that John places on the family. The Hinckley family has been paying for his therapy in Williamsburg out of pocket, “and that is simply not sustainable,” Scott has said.

For his part, at 61, Hinckley would like more than just to pay his own way. In a recent interview with Dr. Patterson, Hinckley talked about his desire to “lead a good life and provide for my mother, which is very important.” And so he does what he can for her. “My mom loves to have me around,” he told St. Elizabeths’ staff. “Like, before I do anything at all in the morning, I get her newspaper because she just loves to have that, so I make sure it’s there first thing.” Hinckley has told doctors that he understands his mother might die, and that in that event his siblings would find him a condo or apartment nearby. That would be his preference, anyway, to “just stay down here and keep living the way I live.”

It’s a curious life. In the past couple of years, Hinckley has picked up photography, and some say his pictures are pretty good. At a support group for the mentally ill, he met a woman named Ms. L. He told his Williamsburg psychiatrist that the relationship was not romantic but that he talked to her on the phone every day — and sometimes to her parents, too. They are like teenagers, his social worker said. Ms. L is not “extremely musically inclined,” Hinckley confided, but when she has come over he let her use his keyboard. As recently as 2015, they were talking about starting a band.

*This article appears in the March 20, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.