The liberal explanation for the result of the election emphasizes Hillary Clinton’s deep personal unpopularity, which grew out of a combination of her own bad decisions, hostile media coverage, an overblown email scandal, and the decisive intervention of FBI director James Comey. Both the right and the far left have drawn different conclusions, which use Clinton’s defeat as an indictment of the entire liberal policy agenda. David Brady, a political scientist at the conservative Hoover Institute, tells Tom Edsall, “Why did Kankakee, Illinois, and Green Bay vote Obama and then Trump? They didn’t become racist and misogynistic over the last 8 years. It has to do with the effects of slow-growth economies over time on people’s psyches.”

The left-wing writer Matt Stoller has made the same point repeatedly. “Obama can’t place the blame for Clinton’s poor performance purely on her campaign. On the contrary, the past eight years of policy-making have damaged Democrats at all levels,” he wrote in January. Trump is “the price we’ll be paying for more than 25 years of failed Democratic policy-making,” he writes this month.

The argument boils down Clinton’s election to a simple causal chain. Obama’s policies led to slow economic growth, which led to voter anger or disillusionment with Obama’s presidency, which voters transferred by proxy onto his successor candidate, Hillary Clinton. This line of reasoning has come to appear so self-evidently true that many analysts on the right and the left have discussed the election as though Trump defeated Obama, with Clinton’s role almost incidental. Many of them assert that those of us who don’t share this belief are in a bubble of elitist denial, failing to grasp the popular discontent with Obama’s status quo.

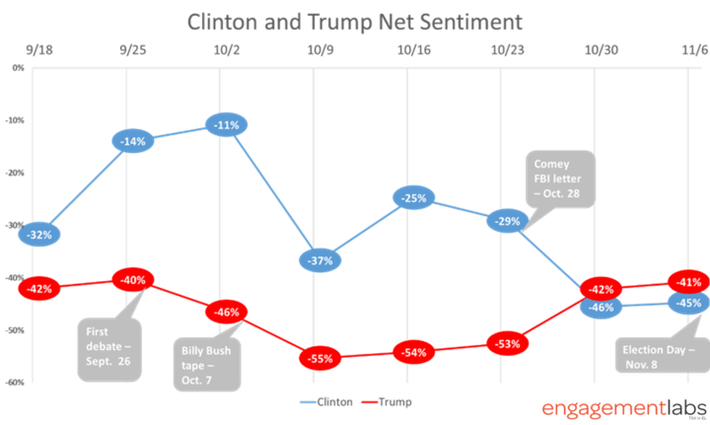

The supposition that Clinton lost because of her association with Obama, rather than despite it, ignores a great deal of publicly available data about both figures. At election time, Obama was quite popular, and Clinton quite unpopular. While Clinton was less unpopular than her opponent through most of the campaign, one recent analysis shows that the floor dropped beneath her support after the Comey letter came out:

If there was a bubble, it was political insiders who saw Clinton’s email issue as a small-bore routine problem, not the image-defining scandal most Americans came to see it as. I know several Democratic political operatives who heard from swing voters who believe Clinton routinely had people murdered. Insiders never saw how badly the email issue poisoned her image, holding queasy Republicans in Trump’s corner and depressing her turnout.

The theory that Obama’s economic policies hurt Clinton also has trouble explaining why Obama was able to win comfortably in 2012. After all, the economy was in worse shape in 2012 than in 2016, and Obama’s approval was higher. So why did economic discontent with Obama hurt Democrats more in 2016 than in 2012?

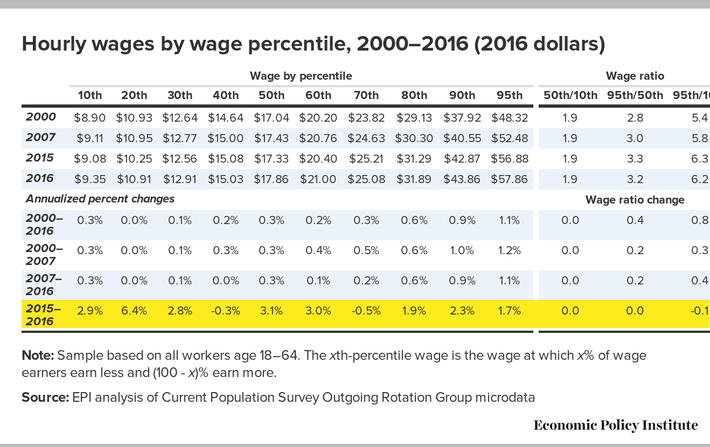

Indeed, the more we learn about the economy, the harder it gets to sustain the theory that Obama’s economy hurt Clinton. Economic data arrives in lags, and is often revised years later before a truly accurate picture forms. Many of the indictments of Obama’s economy rely on old data that does not capture his entire presidency. This turns out to be especially significant. Financial crises tend to produce slow recoveries. The elevated unemployment caused by the worldwide collapse of the financial system took about half a dozen years to come down. During that time, a glut of workers led to stagnant wages. Many of the indictments of the economy during this period reflect data collected in 2013 or 2014. Bernie Sanders repeatedly insisted on the campaign that some huge percentage of wage growth was accruing to the richest 1 percent, which was accurate in the early, slow-growth years of the recovery, but was no longer true at the time he said it.

Since 2015, low unemployment has had the predictable effect of forcing employers to offer better wages to attract and keep their labor force. While incomplete, the data so far suggests wages up and down the income ladder have grown smartly for two years. In 2015, wages actually grew more rapidly at the bottom of the income ladder than at the top:

Growth of jobs and wages continued through 2016 and into 2017, and income trends are likely to show that last year extended the same broad-based growth dynamic as the year before. The slow recovery from the financial crisis eventually yielded an impressive, still-ongoing recovery that is producing broad-based increases in the standard of living.

Many of the indictments of Obama’s policies were formed early in his administration. (Stoller, among others, has been making this critique since Obama’s first term.) There is a case to be made that the fiscal response to the recession was too small, unnecessarily elongating the recovery. That said, the economy under Obama did reach low unemployment and it has, at last, produced impressive wage gains for the working class. If any number of factors had turned out differently, from Comey to WikiLeaks, people would be talking about the Obama-Clinton boom. The evaluations of his economic record that are able to account for all the data will yield conclusions far more favorable than most people afforded Obama at the time. In the meantime, the political credit will accrue to the president who inherited an economy humming along at low unemployment.

Obama’s economic policies may wind up helping Trump after all. But if they do, it will not be because they helped get Trump elected, but because they helped him get reelected.