Donald Trump’s primary criticism of the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has been that it allows Mexico to “kill us.”

Thus, as a candidate, Trump promised to renegotiate NAFTA to Mexico’s detriment — and, ostensibly, to allow America to start “killing” the Mexicans (economically, speaking).

This proposal suffered from the same problem that ailed Trump’s plan to bill Mexico for his border wall: Why would the Mexican government consent to a policy that the American president has publicly described as a burden on the Mexican people? Even if you accept that trade negotiations are zero-sum games, it makes little sense to tell your adversary that you intend to screw them over. Especially when that adversary is a democratically elected politician who will need to sell any agreement to his or her electorate.

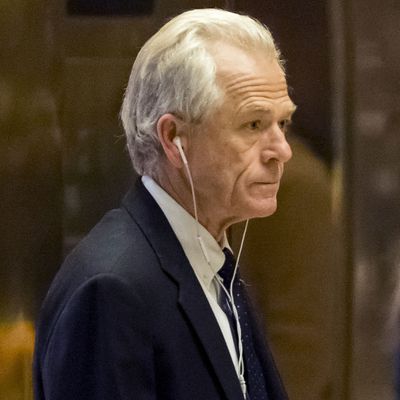

So, it isn’t too surprising that Trump’s top trade adviser, Peter Navarro, plans to take a different approach to NAFTA’s renegotiation.

Navarro is one of the White House’s most committed protectionists — one who has vowed to “repatriate” the global supply chains that power the American economy. But even he doesn’t seem anxious for a trade war with our immediate neighbors. Instead, Navarro has made a slight revision to Trump’s trade philosophy, one that’s bound to play better across a negotiating table from Canada and Mexico — North America first.

Per Bloomberg:

Peter Navarro, who as head of the White House National Trade Council will play a leading role in the effort to re-negotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement, said in an interview the U.S. wants Mexico and Canada to unite in a regional manufacturing “powerhouse” that will keep out parts from other countries.

The Trump administration is re-examining a critical component of the free trade pact: the rules of origin, which dictate what percentage of a product must be manufactured in North America, Navarro said.

“We have a tremendous opportunity, with Mexico in particular, to use higher rules of origin to develop a mutually beneficial regional powerhouse where workers and manufacturers on both sides of the border will benefit enormously,” said Navarro, 67. “It’s just as much in their interests as it is in our interests to increase the rules of origin.”

Under NAFTA’s current rules, 62.5 percent of the value of a car’s constituent parts must originate in the U.S., Canada, or Mexico, for that car to be sold in North America without an import tariff. The U.S. wants to raise that percentage, along with several similar thresholds that apply to other products.

Navarro believes that these rules will allow the U.S. to reduce its $500 billion trade deficit, which he sees as a fundamental obstacle to economic growth.

Other economists argue that America’s trade deficit is driven, primarily, by our low savings rate and our nation’s attractiveness to foreign capital. As Laurence Kotlikoff writes in Forbes:

Our country saves far too little to invest adequately in our country. As a consequence foreigners see good investment opportunities here and make up some of the difference. Investment means adding to the stock of factories, residential structures, and equipment in a country. This additional capital is shipped into our country from abroad, i.e., it’s imported. Alternatively, foreigners sell us products and use the proceeds to invest in locally produced capital. Either way, the trade deficit reflects, primarily, the amount of investment in the U.S. done by foreigners – investment that Americans would otherwise be doing if they saved enough.

Still, Navarro’s view is not exclusive to a radical right-wing fringe, by any means. Progressive economists Dean Baker and Jared Bernstein (who served as chief economist and economic adviser to Vice-President Joe Biden) made the case for reducing the trade deficit in The Atlantic last December:

Trade deficits, even in times of strong growth, have negative, concentrated impacts on the quantity and quality of jobs in parts of the country where manufacturing employment diminishes. Even the economists who argue (incorrectly, we believe) that the trade deficit doesn’t affect the total number of jobs do admit that it affects the composition of jobs

… And trade imbalances have repercussions far beyond the labor market. They can produce significant macroeconomic distortions, and those who view deficits as benign frequently overlook this. Most importantly, as Ben Bernanke noted over a decade ago, a trade deficit can have a role in producing financial-market bubbles and the devastation that’s caused when those bubbles burst. The problem arises when other countries suppress spending and investment, thereby boosting their savings rates and their trade surpluses. By the rules of basic accounting, those surpluses have to flow somewhere, and many flow into America. This further strengthens the demand for and value of the dollar, making American exports less competitive—and thus exacerbating the trade deficit. In the 2000s, these trade patterns helped provide the cheap capital that, in tandem with inattentive regulators, inflated the housing bubble. Almost a decade later, the country is still recovering.

Bottom line: It appears that the economic nationalist wing of the White House is pushing for stricter rules of origin, not a trade war with Mexico. And if that’s the radical end of the Trump administration’s internal debate about protectionism, then markets have little to fear.

And, in fact, the Mexican and Canadian currencies both rallied, shortly after Navarro’s comments were published.