In this week’s issue of New York, DW Gibson talks to eight homeless New Yorkers about why it’s so hard to escape the system, much less fix it. Here, a look back at how the city, and this magazine, responded to the problem in the 1980s. As institutions closed and pushed thousands of people onto the streets, the desire to help them evolved into a fearful wariness.

December 21, 1981 | From sympathy …

In the first year of the Reagan-era homelessness crisis, we called it “the shame of the city.”

Maurice has a face like Michelangelo’s statue of Moses, angry eyes glowing out from the midst of white glaring hair, a patriarchal beard touching his chest, a beaklike nose, and a high-domed forehead.

Long ago, he taught physics at one of the city’s major universities. And now, from the depths of his illness, his language and manner parody a professor’s.

A reporter is writing about the homeless, he is told. Would he mind answering some questions? “Well, it’s the robbery rate. It’s the problem of finding something to eat,” he begins, ticking off the points on his fingertips. Suddenly, he seizes a reporter’s notebook and writes across it the word “Angels.” “Talk to them,” he says. “They know.’’

Maurice appears to be in his early fifties. He carries his belongings in a green knapsack and a plastic shopping bag. He wears a fake-leather jacket, an Argyle sweater, and jeans. His shirt is filthy. From time to time he is badly infested with lice from sleeping on the streets.

However, on the Jewish Sabbath, he often worships at a synagogue on the East Side, donning a clean suit given him by a local church. On these occasions, according to some of the congregation at the synagogue, Maurice can be quite lucid.

“You look a bit like Sandra O’Connor, the Supreme Court justice,” he tells a reporter. He pauses and leans forward and smiles. “You will experience trauma sometime,” he says.

Maurice is believed to spend some of his nights “on the wall,” in a walled-off paved area in front of a multinational bank on Park Avenue. Like a scene from Les Misérables, many homeless people sleep over the air vents, barricading themselves with makeshift “weapons” against muggers and outsiders.

Maurice also has a charge account at a local deli. Sometimes, when he runs out of money, he claims to have funds on deposit there. If the deli personnel are not forthcoming, Maurice calls Legal Aid, or the police, in an effort to extract the sum “owed.’’ Nonetheless, the deli continues to give him credit.

Meanwhile, “it was and is robbery,” Maurice intones, “it was and is a matter of disease …” Maurice is asked where he was born. “That’s sophistry!” he exclaims. —Dinitia Smith

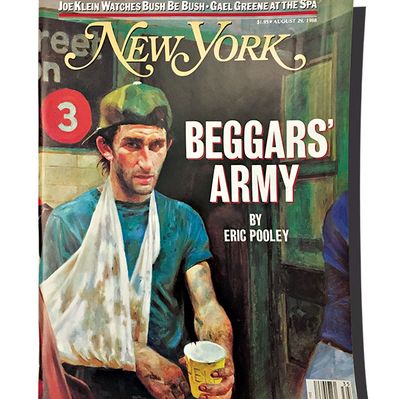

August 29, 1988 | … To frustration.

Seven years later, middle-class New Yorkers were beginning to lose patience with the relentless panhandling.

A large man entered the McDonald’s on Broadway near 96th Street, wearing a red Marlboro cap over a rolled purple hand towel, a blue warm-up jacket, sweatpants, and blue Velcro-flap Nikes. He carried a golf club in one hand and moved edgily from table to table, opening the tops of burger containers, looking for scraps. A woman moved past him toward a trash can, and the man gestured with his club at an unfinished sandwich on her tray.

“Done with that?” he asked.

The woman looked at him with an expression of unalloyed terror, handed over the sandwich, put down her tray, and walked out the door, her high heels clattering on the tile floor.

The man sat down, ate the sandwich, and started asking people for money. More than one looked at him, looked at the golf club, and came up with some change.

“My name is Peter,” he told me. “I’m from Hartford, but I ran away from home three years ago. I couldn’t get along with my father. I thought I’d come to New York and get a job in a factory or maybe a McDonald’s. I filled out lots of applications, but they never called. Now I’m 21, and I live in a shelter in Queens. I guess you could say I’ve given up.

“I don’t beg on the street much, ’cause there’s too much competition. I work the subways. Three months ago, I saw this McDonald’s, thought I’d try my luck. At least it’s out of the heat. Now I come in almost every day, make $2 or $3 and something to eat. They don’t seem to mind.

“I found this golf club on the street a week ago. I carry it so people won’t f— with me — there’s a lot of crazy people in this city, you know that? But since I been carrying it, people give me more money. I don’t threaten nobody” — his eyes, the color of some exotic ceramic glaze, tried for a sincere look — “but they seem more generous now.” He broke into a wicked smile.

“Now that I’ve made a little, I gotta go see a friend of mine, lives in Queens. He’s got his own place, got a good job.”

I asked what his friend did.

“What’s he do? He deals … in computers.”

I asked him if he smoked crack.

“I can’t afford crack. I’m homeless.” He laughed and went out the door. —Eric Pooley

*This article appears in the March 20, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.