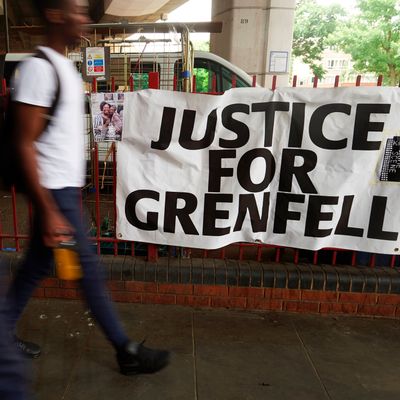

At least 60 high-rise buildings across England have failed fire-safety tests conducted in the aftermath of the horrifying fire that killed at least 79 people inside Grenfell Tower in the North Kensington area of London. As many as 600 buildings throughout the U.K. may have the same type of exterior cladding that is believed to have been responsible for the incredible speed and devastation of the Grenfell Tower fire on June 14. British authorities announced on Sunday that every building that has been examined so far has failed the test, and plans to remove the cladding panels from at least 11 towers are already underway, prioritizing the most at-risk buildings.

As a result, at least 4,000 people have already been ordered to leave their homes while their buildings are refurbished to remove the danger, including the residents of some 650 flats in the Camden area of London who were told to vacate their residential towers on Friday night. Camden Council leaders said they only made the decision to evacuate the towers after firefighters told them they could not guarantee the safety of residents. Some 200 people have refused to leave those buildings, and authorities are still trying to convince the holdouts to relocate.

Not every tower block that has failed the fire-safety test will need to be evacuated, authorities say. For instance, the cladding wasn’t the only concern with the Camden towers, but the fire risk was compounded by the presence of other issues with gas pipes and fire doors. The risk to each building will be evaluated individually, though it seems the cladding will be removed in most, if not all, cases. Displaced residents have apparently been offered free accommodation in nearby hotels. All told, The Telegraph estimates that the cladding-removal effort may cost more than £600 million.

Investigators say the Grenfell Tower fire began when a refrigerator exploded in an apartment on the fourth floor. Since the fridge was near a window, it ignited the flammable, aluminum composite material used in the cladding, which allowed the fire to quickly climb the exterior of the building. The speed and intensity of the fire, coupled with the fact that it spread externally instead of internally, is the primary reason why firefighters were not able to stop it or rescue more people. The cladding, which consists of a panel of aluminum attached to a layer of combustible polyethylene insulation, is typically used as a low-cost way to improve the insulation and appearance of buildings, and the type of cladding which utilizes combustible or fire-resistant materials is less expensive than the type that uses non-combustible materials. Aside from the flammable insulation, the design of the cladding panels also includes a built-in gap that can act as an air channel, feeding and transporting the fire.

Grenfell Tower was hardly the first time this had happened, either. The same type of cladding has already resulted in numerous externally spread fires on buildings in multiple countries. Understanding the risk, manufacturers of the cladding typically advise against using it in high-rise buildings like this one in Dubai, which suffered a similar fire in 2016.

It remains unclear whether or not the companies that ordered or installed the cladding on the Grenfell Tower knew how dangerous it could be during a fire at the building. The company that manufactured the cladding panels used on the tower, Arconic Inc, is already telling the media that it was not its responsibility to make sure building materials were used in compliance with local building regulations. Furthermore, in the case of Grenfell Tower and the other affected buildings in England, local regulations almost certainly weren’t good enough to begin with. According to an extensive new report in the New York Times, the underlying blame for the Grenfell Tower fire, and the risk to numerous other buildings with the same type of cladding, starts with the British government:

[I]nterviews with [Grenfell] tenants, industry executives and fire safety engineers point to a gross failure of government oversight, a refusal to heed warnings from inside Britain and around the world and a drive by successive governments from both major political parties to free businesses from the burden of safety regulations.

Promising to cut “red tape,” business-friendly politicians evidently judged that cost concerns outweighed the risks of allowing flammable materials to be used in facades. Builders in Britain were allowed to wrap residential apartment towers — perhaps several hundred of them — from top to bottom in highly flammable materials, a practice forbidden in the United States and many European countries. And companies did not hesitate to supply the British market.

Fire-safety engineers, firefighters, and members of the British Parliament had sought to restrict the use of the cladding after it was blamed for earlier fires in the U.K. and elsewhere, but their requests and warnings went unheeded. Manufacturers of the cladding fought additional restrictions and testing, citing the additional cost of fire-resistant or fire-proof building materials, and government regulators ultimately didn’t act. Pro-business governments over the past two decades have also pared back existing regulations, for instance leaving fire-code adherence to industry self-policing, rather than government inspectors.

Here in the U.S., fire-safety regulations require that building materials used on any building taller than a firefighter’s two-story ladder be subjected to real-world fire simulations, and the type of aluminum cladding used on the Grenfell Tower failed those tests and is therefore mostly banned for buildings taller than 40 feet. Not every U.S. jurisdiction requires the test, however. NPR reports that Indiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and the District of Columbia have relaxed restrictions in their building codes on testing the cladding, citing the expense of the tests. In those cases, the untested cladding can be used provided the buildings employ other fire safety measures, like sprinkler systems. It is not at all clear that this is a responsible way to save on building costs, regardless of the additional precautions. One fire-protection engineer, John Valiulis, is certain it’s not and has published a white paper since the Grenfell Tower disaster criticizing the relaxed restrictions.

Back in the U.K., the cascading political and policy effects of the Grenfell fire are still just starting. Aside from the ongoing examinations of buildings with the cladding, government ministers have already dropped a cost-saving proposal to relax fire-safety standards in new school buildings. The Observer reports that the policy retreat is part of a government-wide reexamination of existing and proposed fire-safety standards in the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire. If the Times report is any indication, a massive policy shift is badly needed — and long before the criminal investigation and political bloodletting has finished.