Compared to other major democracies, Americans vote in appallingly low numbers. It’s so bad, in fact, that pollsters were pleasantly surprised last month when a measly 13 percent of New Jersey’s registered voters showed up to vote in the gubernatorial primary, up from 9 percent in 2013.

Presidential election years bring out more voters, of course, but even the 2016 national election — featuring a reality TV star and the first woman to win a major-party nomination — drew only slightly more than half of voting-age Americans to the polls. That figure places the United States well below most other major developed democracies, somewhere between Estonia and Slovenia.

But it wasn’t always this way. According to get-out-the-vote guru Donald Green, voting records show that American elections in the mid-19th century drew as many as 80 percent of eligible voters to the polls, a rate comparable to the countries that now boast the highest turnout — places like Belgium, Sweden, and Denmark.

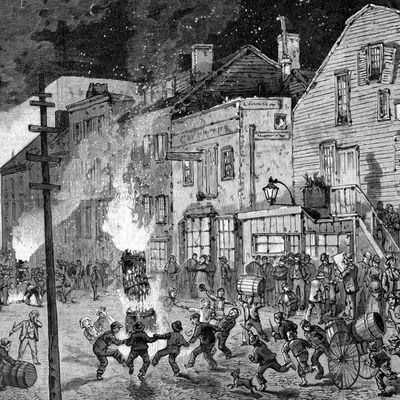

So what changed? Green, a professor of political science at Columbia University, thinks part of the problem is that voting isn’t as fun as it once was. It used to be a raucous, festive attraction, with polling places set up in saloons where voters (white men only, at that point) would spend the day carousing and casting their ballots. Over time, thanks to reforms aimed at making voting a more dispassionate affair, elections became more and more staid, to the point where the biggest excitement is a bake sale and voting often feels more like a trip to the DMV than a July Fourth barbecue.

While no one wants to go back to those days, research conducted by Green has found that organizing community festivals — with everyone invited for things like live music, sno-cones, and hot dogs — near polling sites can create a significant increase in voter turnout, often for less money than direct mail or door-to-door canvassing.

“If I had to bet on one thing that pretty much any organized group could do, it would be this,” Green said. “Right now, the evidence is pretty overwhelming.”

Green’s current research builds on studies he conducted in 2005 and 2006, when he looked at the effect of festivals at 14 polling places in 13 cities across the country, from Green Bay to Tallahassee. He compared festival sites with regular polling places and found that festivals increased turnout by an average of 2.6 percentage points, a relatively big jump in this context.

In 2016, Green carried out his experiments again, teaming up with Civic Nation, a nonpartisan nonprofit that works on encouraging civic engagement. Funded by the Knight Foundation, Civic Nation worked with local partners — who also pitched in resources — to organize festivals at nine sites in 2016. Each was advertised beforehand and geared toward local interests — things like Mexican food, pizza, photo booths, and cornhole – at a cost of between $700 and $3,000.

Green found that the 2016 festivals boosted voter turnout by about 4 percentage points, an even bigger jump. “These effects are kind of eye-popping,” Green said. “Especially when you think of how low the cost per vote was.” Green said he calculated it to between $30 and $40 per extra vote. “That’s pretty darn cheap, because even the most efficient tactics are in that range and it’s certainly better than a lot of common tactics like direct mail or robo-calls.”

The festivals so far have been strictly nonpartisan, aimed at turning out more voters regardless of party affiliation. It’s unlikely the technique could be successfully weaponized as a partisan activity, since it’s hard to prevent a festival from drawing your opponent’s voters to the polls along with your own, said Melissa Michelson, a Menlo College political science professor who studies voting behavior.

And even though Democrats tend, in general, to benefit from higher turnout, polling festivals are still probably not targeted enough to make them a popular technique for Democratic campaign consultants, she said.

Michelson said another obstacle to the spread of election festivals is that efforts to increase voter turnout — and our culture in general — are headed in the opposite direction, toward the digital and impersonal. Election reformers are looking at things like early voting, no-excuse-needed absentee voting, and internet voting. “That’s where the trend is,” she said. “We’re probably going to see a shift toward less personal voting and less community spirit.”

Civic Nation is hoping to buck that trend, by working with Green this year to study polling festivals in about 40 sites and then encouraging people to throw their own parties at elections next year, during the midterm elections in 2018.

Costas Panagopoulos, a Fordham political science professor who studies voting, said other techniques like postcards thanking people who vote, or even shaming those who don’t, show more promise than polling festivals. He said he doesn’t expect to see festivals take hold nationwide anytime soon, given how much local organization is required, compared to a mass mailing.

“It’s certainly the case that there are other, more scalable ways of generating votes,” Green said. But, he said, while postcards might become less effective over time, polling-place festivals have the potential to create a real cultural shift, establishing a tradition of Election Day fun that might build on itself year after year. Green noted that this kind of festive voting tradition already exists in Puerto Rico, and voting rates there have historically exceeded 80 percent.

“The way I can imagine this happening is for some communities, some towns or larger areas, embracing this as a thing they do routinely. And you have school marching bands play and you have all the accoutrements of a community activity that draws a broad spectrum of people,” Green said. Voting has gotten dull, he said, “but it doesn’t have to be that way.”