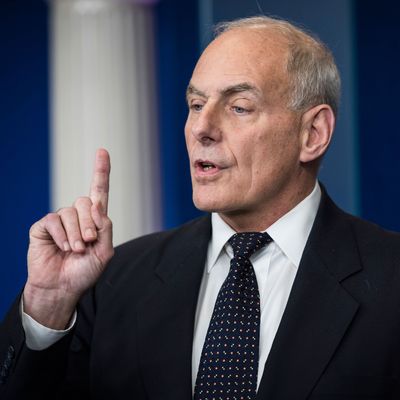

Last night, in an interview with right-wing talk-show host Laura Ingraham, White House chief of staff John Kelly expressed his view that the Civil War was the tragic result of “the lack of an ability to compromise,” fought between “men and women of good faith on both sides,” including the “honorable” Robert E. Lee. Today, White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders defended Kelly’s comments, citing, among other sources, the Ken Burns Civil War documentary.

The uncomfortable truth for progressives who loathe the Trump administration and wish to treat it as a malignant outlier on all things is that Sanders is right about this. Not about the history — Kelly’s romanticized view of Lee and the Confederacy, and the supposed possibility for compromise, ignores the reality that both were fanatically devoted to the brutal subjugation of African-Americans at any cost — but about Burns’s documentary, which I watched not long ago, and which tells substantially the same narrative as Kelly.

For all the technical skill Burns brings to bear on his subject, which he brings to life without any historical footage, his analytic framework is a disaster. Burns relies heavily on Shelby Foote, a novelist and quasi-historian whose ability to spin colorful tales gobbled up large chunks of airtime. Foote presented Lee and other Confederate fighters as largely driven by motives other than preserving human property, and bemoaned the failure of the North and South to compromise (a compromise that would inevitably have preserved slavery). Kelly’s claims to Ingraham last night are an almost verbatim recapitulation of Foote’s account:

But the failure belongs less to Foote than to Burns. It was Burns who chose to give Foote literally nine times as many appearances as Barbara Fields — a real historian whose perspective Burns scants. (In an interview two years ago, Alyssa Rosenberg pressed Burns on the discrepancy, which he adamantly defended.) Foote’s perspective dominates the film in ways that go beyond his own commentary; Burns centers the story around individual people, rather than as the militarized culmination of a long political struggle. Burns does not dismiss the existence of slavery, but he implicitly treats it as disconnected from the war — a choice reflected in the narrative structure, which is broken into three discrete groups: the North, the South, and the slaves.

Some allowance could be made for the period during which the documentary was made, almost three decades ago. And it is surely true that Burns was repeating a version of the revisionist history in which most American schoolchildren were then steeped, and many still are. A 2011 poll found that 48 percent of Americans identify states’ rights as the war’s main conflict, while only 38 percent identify it as slavery.

There are many ways in which the Trump administration has radically departed from the civic consensus: its ugly demonization of immigrants, the president’s insistence that the Nazis of Charlottesville were “good people,” his insistence that a child of Mexican immigrants was unfit to judge his fraud trial, and so on. But, in this instance, Kelly’s nostalgia for the Confederacy reflects not some grotesque aberration, but a broader failure of American culture and memory.