In recent weeks, the president of the United States has attempted to use his bully pulpit — and a couple hundred thousand dollars in taxpayer money — to get African-American football players fired for protesting police violence in a manner that offends him. Meanwhile, the White House publicly encouraged a news organization to fire a commentator who had called the president a white supremacist.

The NFL initially resisted Donald Trump’s bid to police their players’ speech. In a show of solidarity, several NFL owners locked arms with their players during pre-game performances of the national anthem. Iconic Dallas Cowboys owner, Jerry Jones, even performed the very same kneeling gesture that had attracted the president’s ire.

Nevertheless, Donald Trump and his acolytes persisted. And the NFL’s ruling class quickly decided that the “deplorables” posed a greater threat to their profit margins than the risk of labor strife. On Sunday, Jerry Jones announced that any Cowboys player who “disrespects the flag” (by failing to stand for the national anthem) would be benched.

Shortly thereafter, ESPN’s Jemele Hill — the anchor whom the White House had recently tried to expel from the airwaves — offered her Twitter followers some insight into the forces that drove Jones’s change of heart. Financial pressure from fans had inspired Jones to rescind his players’ civil liberties — and, thus, financial pressure from a different set of fans could lead him to restore the Cowboys’ free-speech rights.

One day later, Hill clarified that she was not advocating a boycott, only arguing that such an effort would influence Jones’s calculus without (directly) hurting his players.

This was cogent analysis. Hill’s job is to offer commentary that deepens (and/or challenges) her audience’s understanding of the latest developments in the sports world. These tweets fit that bill.

But they also undermined ESPN’s financial interests. Jerry Jones and the sports network share advertisers — broadcasting NFL games is a core part of the latter’s business. And ESPN’s advertisers are not paying the outlet millions of dollars to discourage people from buying their products.

If ESPN were a primarily journalistic enterprise — which is to say, an entity whose first priority was to keep its audience well-informed about its interests and world, even when powerful interests would prefer a more circumscribed public conversation — then it would have taken Hill’s tweets in stride.

After all, this whole controversy began with the executive branch launching an attack on public dissent. The Trump administration halted Justice Department investigations into police abuses in black communities, and then tried to silence African-American athletes who protest such abuses — while simultaneously encouraging ESPN to fire an African-American reporter for suggesting that its policies were motivated by racial animus.

If journalists have one civic responsibility, it is to prevent power — especially state power — from dictating the terms of public discussion. So even if Hill’s tweets caused consternation with advertisers, ESPN should have avoided any disciplinary action that might encourage the White House to make further interventions in the Fourth Estate’s affairs.

But ESPN is a primarily commercial enterprise. Like the NFL, its first priority is to make money. Its responsibility to shareholders overrides all obligations to the public. And so Jemele Hill will not be appearing on ESPN for the next two weeks.

ESPN viewers who object to this decision should lobby the company to reverse it. Perhaps an organized pressure campaign can change the network’s understanding about where its true financial interests lie. But Hill’s suspension points to a broader peril in the way we fund journalism in the United States, one that can’t be eliminated by consumer activism.

The conflict between journalists’ civic responsibilities and for-profit company’s fiduciary ones is not peculiar to ESPN or sports networks, but endemic to virtually all American media. A democracy cannot function without a well-funded, adversarial press. But market incentives do not adequately reward news outlets for investing in high-impact investigative journalism, or for covering politics with an emphasis on policy instead of spectacle.

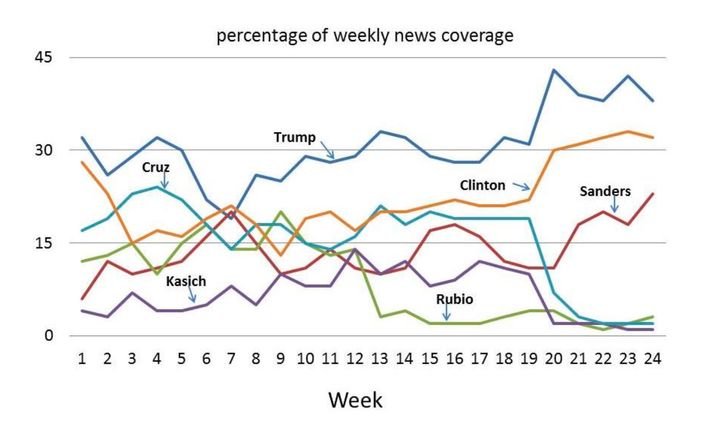

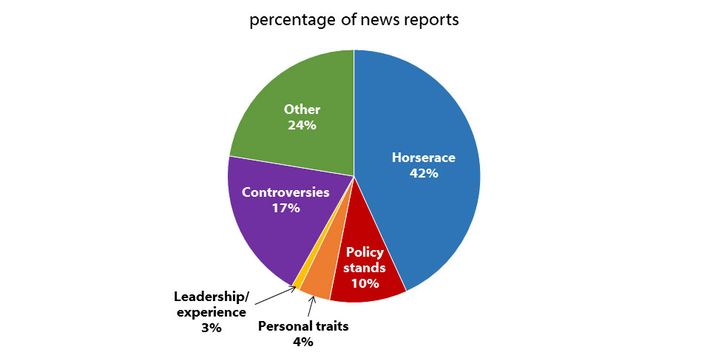

In the early days of Donald Trump’s presidential bid, cable news networks showered the mogul in free airtime — in some instances, broadcasting entire Trump campaign rallies, uninterrupted by commentary or factual correction. There was little public benefit in airing what were, in essence, unpaid infomercials for a reactionary demagogue, but there was a tremendous financial interest in doing so: Reality stars play well on television. As CBS CEO Les Moonves would eventually infamously say of Trump’s candidacy: “It may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS.”

Similarly, financial incentives led the news media to collectively devote a mere 10 percent of their campaign coverage to each presidential candidate’s policy positions, according to the Shorenstein Center’s analysis. (Treating politics as a slow-motion sporting event may not be good for the republic, but it’s damn good for eyeballs and clicks).

The market also rewards outlets that can maintain access to power brokers in both parties, and appeal to the broadest possible audience. One might argue that many news organizations’ obsessive focus on Hillary Clinton’s email controversy was informed by a desire to balance negative Trump coverage, and thus to protect their insider access and breadth of appeal.

And then, of course, there’s the fact that Trump’s entire political persona — and the movement that brought him to power — owe their very existence to the way that the media market has rewarded right-wing propagandists who demonstrate a talent for selling elderly white people racial paranoia and gold bricks.

It’s true that since Trump took office America’s two major newspapers have done plenty of vital work, while cable-news networks have discovered a beneficent passion for on-the-fly fact-checking. And when one looks at how cable-news networks have treated their more adversarial anchors in 2017 — and recalls how they treated Iraq War skeptics who displeased their advertisers during Bush’s first-term — it’s not hard to see some signs of progress. But, then again, the adulation that attended Trump’s air stike in Syria last spring suggests our media’s appetite for spectacular displays of American military power remains voracious.

Regardless, the problem with relying on for-profit entities to execute journalism’s civic function extends well beyond Trump. Between 2003 and 2014, the number of full-time newspaper reporters assigned to state capitals contracted by 35 percent, according to the Pew Research Center. In an era of legislative gridlock on the federal level and right-wing policy revolutions in the states, the media market is allocating ever fewer resources to the project of keeping the public well-informed about the latter.

In an incisive 2016 column, The Week’s Jeff Spross argued that the mainstream media’s coverage of Trump constituted what economists call a “market failure”:

The point of markets is to use property rights and price signals to coordinate human behavior. This is so that our societies wind up generating more of the goods and activities that make us better off, and less of the stuff that harms us. But markets are also imperfect human creations, so the price signals that are supposed to efficiently coordinate human behavior can get screwed up.

Pollution is an obvious case. The ability to pollute benefits some specific economic actor or industry, like power plants. But the harms are spread out over the whole population, and the damage to health and ecosystems often takes years to show up. This makes it very hard for property rights and price signals to naturally create a system where the people harmed by pollution can charge polluters for the damage. So government has to step in, most often with regulation.

…A public discourse that prizes substantive issues and serious debate over the clown show of a racist demagogue is (or should be) a first-order moral goal of our society. But our markets and related institutions, as they exist, aren’t delivering it…[I]t’s also a market failure in the sense of pollution: The benefits of covering Trump are felt specifically and immediately by the media industry in terms of traffic and profits, not to mention the immediate enjoyment of readers. The costs — a degraded public discourse and political process — are more diffuse and only emerge over time.

Americans disturbed by Hill’s suspension may be able to reverse it by engaging ESPN as consumers. But to combat the broader ills that our for-profit media market produces, they will need to engage their government as citizens.

Of course, increasing government regulation of the Fourth Estate is the opposite of what’s required in this moment. What we do need is a mechanism for dramatically increasing the funds available for outlets that practice public-interest journalism, without compromising said outlets’ editorial independence from the state. One alternative would be for the federal government to provide states and localities with permanent funding streams to subsidize metro reporting outlets. Or, if we wish to avoid giving any government entities discretion over which outlets get funded, Uncle Sam could provide each citizen with a voucher to be spent on a subscription to the local newspaper — or national, nonprofit news outlet — of his or her choice. This would preserve an element of free-market competition in the media sphere, while making local and nonprofit outlets less dependent on advertising revenue or the largesse of big-dollar donors.

Neither of these reforms would be free of flaws or solve all that ails our Fourth Estate. But given how impoverished and polluted our public discourse has become, it’s past time to explore alternatives to the media market’s invisible hands.