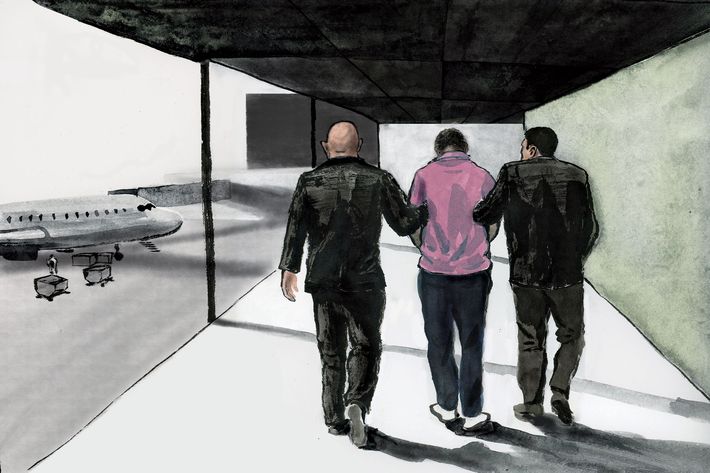

Abdullahi Yusuf was just 3 years old the last time he’d been on an airplane. But when he walked into the Minneapolis–St. Paul airport 15 years later, he tried to look like he’d been traveling all his life. He wore brand-new khakis and a pink oxford shirt — casual travelwear, he thought. He’d considered packing painkillers and antibiotics in case they didn’t have medicine where he was going but abandoned the idea for fear it would arouse suspicion at security. He was struggling to keep his emotions in check. “It was my last day with my family,” he said. “My last day in America. The last day of life as I knew it.”

Although Yusuf had turned 18 earlier that spring, his morning ritual still included his dad driving him to school. The ride that particular May morning had been excruciating — how could he make small talk? When they finally pulled up to the school, he suddenly threw his arms around his father’s neck and held him. “He thought that was strange,” Yusuf said. “But I thought it was my last time seeing my dad. I wanted a good memory.”

Hours later, Yusuf had made it through security. Someone helped him find his gate, and then he waited, reviewing his plan: Pass Customs in Istanbul, go to the Blue Mosque. That was where he’d arranged to meet a friend of his — another Minnesota teenager, named Abdi Nur — who’d be leaving for Istanbul the next day. “Then we had to get a hotel, call a number, and make our way down to Syria.”

They were off to join ISIS.

Yusuf still remembers the tiniest details from that afternoon: the feeling of his new passport in his pocket; mentally measuring the distance to the Jetway. Fifteen feet, ten feet, six feet. I’m finally doing it. No turning back now, he thought. Then two middle-aged men in suits materialized on either side of him. “Abdullahi, we need to talk to you,” one said. “You aren’t flying today.”

That’s when Yusuf knew: “I’m fucked.”

By the time I sat down with Abdullahi Yusuf in the fall of 2016, he’d already pleaded guilty to terrorism charges and was in jail awaiting sentencing. We talked periodically until a judge imposed a gag order, which often happens in high-profile national-security cases.

In 2008 and 2009, I’d worked on a series of stories for NPR about what at the time was the largest terrorist-recruitment case in America: young Somalis leaving Minneapolis to join the Shabab, a Somali Al Qaeda affiliate. Five years later, ISIS’s recruitment efforts here seemed similar, but Yusuf’s case came with a singular twist. While he awaited the judge’s ruling on prison time, he was enrolled in what might be described as a jihadi rehab program — making him the first admitted terrorist in the United States to be given this kind of shot at redemption.

If you didn’t know the trouble he was in, Yusuf would be that kid you hoped your child would become friends with. Six-foot-four with dark skin and cropped hair, he stands up when you enter a room and offers a hand to shake. There’s an appealing earnestness about him, and he moves in the loose-limbed way of natural athletes, which makes him seem younger than 20.

During our first meeting, in the U.S. Attorney’s office in Minneapolis, he was wearing a dark-green Department of Corrections uniform that swam on him. No surprise that his friends call him “Bones,” I thought — he was skeletally thin. Yusuf had never talked to a reporter before, he told me, and wasn’t sure how it was supposed to go. As an icebreaker, I asked what he was reading. He broke into a grin. “Infinite Jest, by David Foster Wallace. But it’s upsetting me. I’m like, I don’t understand it.” Then he brightened and asked, “Have you ever read Foucault?” I nodded, and he kept talking, warming to the subject. “He’s hard to get into, but yeah, he’s smart. It’s the detail he gets into, right? When he talks about the Panopticon … reading about being incarcerated while incarcerated — it’s very, I don’t know. It makes you more observant of the little things … like how the government works, and stuff like surveillance. I never thought there would be a philosophy for that.”

“Is Foucault your favorite French philosopher?” I asked.

“No, because I only know one French philosopher,” he replied.

Since 2013, the number of Americans lured by ISIS to join its ranks in Syria and Iraq runs into the hundreds. Most are young and never make it out of the United States; law enforcement either steps in before they can board flights or reveals their plans to their parents, who shut them down. While thousands of Europeans have shown up on the battlefield in Syria, intelligence officials believe only a few dozen Americans have fought or are fighting for the group. Of that handful, at least seven are from Minnesota and had some contact with Abdullahi Yusuf.

He was born in a refugee camp in Kenya in 1996, and his most salient childhood memory is having his tonsils removed by a “camp witch doctor,” who didn’t use anesthetic. (He remembers lots of blood.) His family was granted refugee status when he was a toddler, and Yusuf moved to the States with his mother, little brother, and other assorted family members. Yusuf’s father, Sadiik, wouldn’t join them until five years later. The first summer Yusuf spent with his dad was “the best ever,” he told me. Sadiik “played soccer every day” with his two sons and took them to the zoo.

Yet that first summer wasn’t entirely sweet. His father was jumped while driving a taxi. According to Yusuf, two “military men” asked Sadiik if he was Muslim, and when Sadiik said yes, “they beat the living daylights out of him. He had to go to the hospital. I mean, that made me feel like ‘the other,’ you know?” Looking back on it, there was always a whiff of anti-Muslim bias in the air, Yusuf told me. After the 9/11 attacks, he heard his share of terrorist jokes. “The kids didn’t mean it like ill will. But it put a doubt in my head about who I am and how I fit in.”

If there was a time when Yusuf felt most American, it was when he became a citizen at age 15. “The ceremony, it felt good. You get a certificate, you get a little flag.” He later helped his parents study for their naturalization tests, which is harder than it sounds. Even though they’d been in the States for more than a decade by then, they didn’t speak much English, and he didn’t speak much Somali. (His mother still mostly speaks Somali.) “Trying to teach, you know, democracy to my parents, that was challenging,” he said. Eventually the entire family passed the exam. “This was around election time and President Obama, and my mom was so excited to vote.”

During Yusuf’s freshman year in high school, the family moved to Burnsville, a bedroom community 15 miles south of Minneapolis–St. Paul. This is where his parents hoped that he and his younger brother would flourish, away from what they thought were the drugs and gangs and crime of the city.

To Yusuf, Burnsville and its high school looked like something out of the movies. “There were the jocks and the guys with letterman jackets,” he said. To fit in, Yusuf tried out for the football team. He became one of just two Somalis on the JV squad. “I tried to go to every game,” his father told me. “And every time he got hit, I was so worried he wouldn’t get up. He was so skinny, and the other guys were so big.” Yusuf always got up.

When football season was over, Yusuf said, “I was like, Oh my gosh, what am I going to do after school now?” While the guys he used to hang out with were still friendly enough in the halls, over time they went their own way, and Yusuf “just started hanging out with people who looked more like me.” The Somali kids. They had their own clique in high school, and by Yusuf’s account, they weren’t up to much good. He started smoking pot, staying out late, even stealing cars.

Syria wasn’t on Yusuf’s radar until later, when a high-school teacher assigned students to study various countries and he got that one. “It was totally random; we didn’t get to choose. You had to research it, make a poster, a presentation. And the first thing I saw were the embargoes the U.S. was placing on Syria. Then I went on YouTube and typed in ‘Syria’ and right away I saw civil war and stuff like that.”

That was in the fall of 2013. The United Nations had just accused the Syrian government of attacking civilians with sarin gas. Videos of the aftermath were all over the web — dead women and children laid out in rows — and President Obama had made his famous “red line” declaration about a chemical attack. “I knew there was something that needed to be done, but I didn’t know what I could do,” Yusuf said. “So I started following everything that was going on there.”

Yusuf also continued to get into trouble, and in hopes of avoiding a run-in with police, his mother and father decided to transfer him out of Burnsville to another school. When his behavior didn’t improve, they transferred him again, and then a third time, to a place called Heritage Academy. That Syria assignment? He said he never finished it.

“Transferring him around his senior year was hard,” said his aunt Hamdi Hudle, who’s only a few years older than Yusuf and close to him. “He was just having fun. He was like a typical teenager, and we felt like, He’ll just grow out of it. He was studying hard [at Heritage] to catch up on his credits so he could graduate and go to college. We thought the problem was solved.”

What Hudle and Yusuf’s parents didn’t know was that an old friend of his, Hanad Mohallim, had also landed at Heritage. They wouldn’t necessarily have been concerned — the two families had known each other since their sons had been freshmen at Burnsville, but it turned out that Mohallim was following events in Syria too. One day when they were on a train coming back from lunch at the Mall of America, “he showed me a video on his phone where this guy was being told to kiss Bashar al-Assad’s picture, and he refused and soldiers were kicking him in his mouth,” Yusuf said. “I thought he [Mohallim] was at the same point as me: you know, just keeping up with this current event.”

A couple of weeks later, his friend vanished.

Days after Mohallim disappeared, an older kid whom Yusuf knew only loosely, Guled Omar, offered to pick him up after school. Almost as soon as Yusuf climbed into the car, Omar asked him what had happened to his buddy. “I was like, ‘Dude, I have no idea.’ ” He’d actually heard around school that Mohallim was “chasing heaven” in Syria and that his mother had flown to Turkey to search for her son. But those were only rumors, so Yusuf kept them to himself. He now believes Omar assumed that he knew what Mohallim was up to and was testing his ability to keep a secret.

Yusuf discovered later that Omar was deeply involved in an underground effort to send young Somalis overseas to fight. The FBI had stopped him at the airport trying to fly to Somalia to join the Shabab in 2012; his brother had joined the group a couple of years earlier and was wanted by authorities. (The FBI had never had enough evidence to charge Omar.)

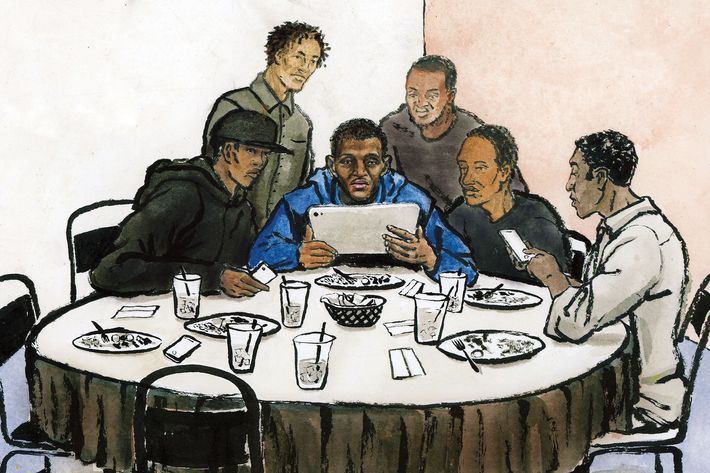

It started to dawn on Yusuf that something bigger was going on when Omar took him to a Somali restaurant that night for dinner and then to a local community center, where kids from the neighborhood mysteriously began to appear, squeezing in next to one another, dragging tables over to join the discussion.

Later that evening, they were all sitting together in a circle. “There were a lot of people I knew before, mostly religious young Somalis,” Yusuf said. “There was a real sense of brotherhood and belonging. It felt like they were welcoming me into something.”

They began passing around cell phones and tablets. “It’s like, ‘Hey, watch this,’ or ‘Hey, watch this,’ ” he said. Some of the videos showed young people training to fight the Assad regime in Syria. In all his research for his Syria project, Yusuf had never seen anything like it. He was “mesmerized.” “It’s like the message is for you. Get up off your butt if you don’t like it. And, you know, it’s just check, check, check, that’s me, that’s me, that’s me.” I asked if he thought he made the decision to go that night. “I don’t think I made it that night, but it strongly impressed me.”

Watching the ISIS videos became a compulsion for Yusuf, like deciding to watch “just one more episode” of Game of Thrones. He found himself awash in another reality, one in which he too could be a noble warrior instead of a helpless bystander. He went from bingeing on videos of ISIS fighters and atrocities in Syria to the lectures of Anwar al-Awlaki, the American-born radical imam who has almost single-handedly shaped the views of violent American jihadists. (He was killed in a U.S. drone attack in 2011.) “He’d say stuff like, ‘Muslims don’t belong in the West … the ones here are confused.’ Stuff that made America look bad.” (Sayfullo Saipov, the man accused of driving a truck down a bike path on the West Side of Manhattan, killing eight people, had al-Awlaki videos on his cell phone. YouTube started blocking al-Awlaki’s channels in November.)

More than ever before, Yusuf began to wonder whether he truly belonged in America or had any chance of making it here. “I mean, we’ve been here for 18 years, and in my family only one person has graduated from college,” he told me, referring to Hudle, his aunt. Granted, his parents had always bought him what he needed, but his dad drove a school van and they lived in a small apartment. “I didn’t know anyone successful,” Yusuf said. “The American Dream seemed unachievable for someone in my shoes.”

Without Mohallim — his best friend, the guy with whom he’d gone to driver’s ed and studied for college boards — Yusuf began spending all his time with Omar and the other Somalis, watching videos, ordering pizza, talking Syria. “The guys became my family. My parents thought I was becoming more religious, and they didn’t necessarily see that as a bad thing.”

The ultimatum came a few short weeks later. “Guled and the rest of the group took me out walking, and I remember what he said: ‘Abdullahi, we’re on a long and hard journey. We’re going to Syria to fight, and you can join us if you want to, but if not, if you turn around and walk away right now, there are no hard feelings.’ ” It took just a beat for Yusuf to respond. “Sign me up,” he said.

How could anyone make such a life-altering decision so quickly? Yusuf said that was baked into the indoctrination. “Hesitation means you’re not a true believer. So if the message resonates with you and you still sit back and lollygag, you know, you’re not on the right path.”

I burst out laughing. I didn’t expect Yusuf to use the word lollygag.

It was less the ideology than the “sense of adventure” that attracted him, he said. Then, the pictures on Instagram. “Them having nice villas and nice cars and stuff like that.” And the wives. The ISIS fighters also got wives. I asked Yusuf if that was enticing too. He blushed. “I didn’t think about that. I was 17,” he said and laughed.

The night before he was supposed to leave for Syria, Yusuf sat in a car, talking to Abdi Nur, the guy he’d be meeting in Istanbul in a few days. The two teenagers were excited about the new direction their lives were going to take. “He was telling me what it was going to be like when I went over there,” Yusuf recalled, “even though he’d never been there.” Sure, they were going to get homesick, Nur said, but they had to stick it out. They were going to be members of ISIS’s special forces, like the Navy seals or Green Berets. “When we get there,” Nur told him, “we’re going to train harder than anyone and be the best soldiers possible.” Just like that — it was going to be that easy.

Then he added one other piece of advice: Don’t hand over your passport to ISIS — that way, they won’t be able to send you back to America to attack. What? No one had ever mentioned returning to the United States to set off explosives or anything like that, Yusuf said.

Yusuf might actually have made it to Syria were it not for his bungled visit to the passport office. A few days after Yusuf’s 18th birthday, Omar gave him $200 and told him to get an expedited passport. Just say that you’re going on a senior trip for graduation, Omar instructed. “He made it sound like a cakewalk,” Yusuf said.

“There was a long line, and when it was finally my turn, the guy seemed very suspicious: asking who I was going to meet, where I got the money, where are your parents.” Yusuf said he’s a terrible liar, so he stammered and sweated his way through the questions. As soon as he left, the passport office called the FBI.

Yusuf’s father remembers the knock on the door, two men filling the doorway. “Do you know this young man?” one asked, holding out a photo of Abdullahi. He was at the airport, the agents informed Sadiik. “I said, ‘That’s impossible, I dropped him off at school myself.’ ” A half-hour later, the phone rang. It was Abdullahi; the FBI had allowed him to leave the airport. “Dad, don’t let anyone in the house, don’t talk to anyone,” he began breathlessly.

“There are some very interesting men here,” his father replied. “Why shouldn’t I be talking to them?”

“Wait for me to talk to you first,” Abdullahi pleaded.

“Why don’t you just come home,” his father said, and hung up.

The FBI agents were gone by the time Yusuf walked in, but his parents were waiting for him. “My mom was yelling at me, asking me how I could’ve done what I was accused of,” Yusuf said. “My dad was very quiet, staring, like he was in shock. They were just devastated.” The gravity of the situation finally hit him. “I thought I’d be far away and could make a phone call and make amends. They’re my parents — they have to forgive me. That sounds stupid … now.”

Yusuf’s family hired a lawyer, though he was convinced his case would never amount to anything. He hadn’t left the country or “participated in an event,” as he put it, so he’d be fine. Other guys he knew had been stopped boarding planes, but they were “still free and doing what they’re doing, still plotting on leaving.” If I just go to summer school, Yusuf told himself, get a job, get into college, things will get back to normal. But he was wrong.

“[My lawyer] was talking about conspiracy to commit murder and conspiring to provide material support,” Yusuf said. “I thought, Holy crap, I’m guilty of what he’s talking about.” The FBI came for him six months after his aborted flight.

By the time the Bureau wrapped up its investigation, ten of Yusuf’s friends had been charged with terrorism offenses, two in absentia. Eventually, he and four others would plead guilty, and the remaining three, Omar included, would go to trial.

It was Judge Michael J. Davis, a 70-year-old former public defender appointed to the federal bench by President Bill Clinton, who decided to give Yusuf a second chance. Davis has presided over nearly all the terrorism cases that have come through Minneapolis, and he leveled hefty sentences on the first wave of Shabab enlistees. But the ISIS followers were younger — teenagers, he noted — and thus perhaps candidates for reform. Maybe what motivated them was less a hard-core commitment to radical Islam, he thought, than the impetuousness of adolescence, an underdeveloped sense of the meaning and consequences of their actions.

Why Davis chose Yusuf in particular for this grand experiment is unclear. (The judge declined to be interviewed.) Was it that no one in his family had tried to join a terrorist group, or that he’d never been in serious trouble before? Or did Yusuf somehow seem less hardened than the other ISIS volunteers, more amenable to new points of view? Whatever the judge’s rationale, he assigned one of the best lawyers in the federal defender’s office, Manny Atwal, to his case and told her he wanted her to get local Somalis involved; the hope was to demonstrate that the community itself could help turn young men away from extremism. To lead the ad hoc transformation effort, Atwal and another lawyer suggested a nonprofit called Heartland Democracy, which works with troubled kids and adults. “Don’t let me down,” Davis told Yusuf. “I’m giving you an opportunity here.”

When the news broke that the judge had suggested counseling for Yusuf and could release him to a halfway house, headlines in Minnesota warned that a terrorist might soon be on the loose. Heartland executive director Mary McKinley, who became one of Yusuf’s main advisers, admitted that while she always has her antenna up for young people who are just telling her what she wants to hear, she was especially wary of her new charge. “I knew enough from people who’d worked with terrorists that oftentimes these people can be extremely charming and manipulative and smooth,” she said. “You can feel a slipperiness about them.”

But from the moment McKinley met Yusuf, there was something different about him. He wasn’t slick, nor was he belligerent or “completely disengaged” — typical behavior for kids forced into counseling. “We just started chatting,” she said. “He had questions for me: What was Heartland? What did we think we were doing when we were working with kids and adults? He was curious.”

Yusuf told me that while he tried to go into counseling with “an open mind,” he initially felt more skeptical than anything else. How could this “white lady” possibly change his mind? “I remember this clearly: I asked her what could I have done in the spring of 2014 at 17 years old to be helpful to those people in Syria and not have been charged for a crime, like something meaningful. She said, ‘Well, I’m in charge of that, and I’ll teach you what you need to know.’ ”

One inspiration behind Heartland’s program is research that suggests that a part of the brain that neuroscientists liken to an internal compass, called the insula, can be built up during adolescence through critical thinking and self-reflective practices. “The insula can actually change and grow,” said Dan Siegel, a UCLA neurobiologist and author of Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain. With a thicker insula, Siegel said, a young person might be more likely to recognize, “Yes, I have an impulse to join that group, but no, I won’t, because I have an internal guide pointing me in a different direction.”

Put in conventional psychological terms, Yusuf “had been allowed to lead this very unexamined life,” offered Ahmed Amin, another of his counselors and an assistant principal in the Minneapolis public schools. “If that’s how you exist when you’re introduced to certain propaganda, you’re more likely to fall into it.”

Part of the problem, said Amin, who is also Somali-American, is that there’s a kind of conversational blackout in schools regarding ISIS, jihad, and Muslims living in the West. Educators fear being accused of, on the one hand, “fomenting” radicalism and, on the other, “stigmatizing Muslims.” The upshot, Amin said, is that “teenagers find the answers themselves.”

During their first meeting, McKinley pushed a stack of books across the table to Yusuf and asked him to choose. “You’re going to have a lot of time on your hands. You might as well read.” There was A Testament of Hope, by Martin Luther King Jr.; A Raisin in the Sun, by Lorraine Hansberry; Milan Kundera’s The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. He chose The Autobiography of Malcolm X. “The back of the book was talking about his shift from radical Nation of Islam black extremism and black nationalism to regular Sunni Islam,” Yusuf said, “and I’m like, Hmmm, this is something in my backyard.”

Months later, Yusuf could still talk about the book as if he’d read it yesterday. “It begins with his identity crisis. He didn’t know who he was … Malcolm Little was born in Nebraska. He went through a lot of phases in his life, stuff like he got in trouble when he was young and went to prison. But in prison he did something most people don’t do — he bettered himself, you know, as a human being. His extremist outlook got changed, and he describes it all in the book.” Yusuf smiled. Obviously, this could be his story too.

McKinley also asked him early on to write a poem, her only prompt that he start each sentence with “I am.” “I just took pencil to paper and wrote,” Yusuf told me. “I’d never written a poem. I tried to make it rhyme.”

I am an alleged terrorist.

I am not sure how that makes me feel.

I throw a fit.

I am currently drinking Sierra Mist.

I am in a hole.

I am sure it’ll take quite a toll.

I am thankful I am whole.

I am bold.

I am labeled.

I am Somali.

I am jolly.

I am a hoodlum.

I am Muslim.

I am black.

I am this.

I am that.

I am sure of one thing for a fact:

I am a human.

It was 18 lines of the kind of introspection Yusuf had never attempted before. McKinley was giving him a one-on-one version of a civic-engagement curriculum Heartland had developed for at-risk kids. Over the course of the next two years, someone from Team Yusuf would meet with him or call him with assignments or new books to read every couple of weeks. Whenever he discussed a book with McKinley or Amin, they pressed him not to just regurgitate what they’d said but to offer his own opinion.

In response to an essay by Native American author Sherman Alexie, for instance, Yusuf told McKinley this: The author was suggesting that “we humans have reservations in our heads: mental blocks about a variety of things, religion, politics, culture.” Alexie’s bottom line, Yusuf concluded, was that each of us “needs to explore and come to our own conclusions. Escape mental slavery.”

Some of what influenced Yusuf’s shift in attitude toward ISIS was dictated by circumstance. The summer before he was arrested, ISIS began beheading journalists. “I didn’t sign up for that,” he said. And while in jail, he learned that it appeared Mohallim had been killed in Syria. “I just cried.”

McKinley genuinely believes that Yusuf has changed, though she’s not convinced it’s the result of the extended tutorial. He may have simply grown up and out of his adolescent ideas. “He doesn’t flatter you. He doesn’t try to charm you in the way that people do when they’re trying to win you over. I mean, in a lot of ways that’s how he got caught, because he can’t fake it.” It’s that quality, too, that may have allowed him to rethink his whole interaction with ISIS, she said. “He’s been able to admit to himself, ‘Wow, I just really had that wrong.’ ”

The federal courthouse in Minneapolis is a tall, salmon-colored skyscraper. In front, there are sculptures by Tom Otterness: bronzes of cartoonlike characters mowing a mound of grass and raking leaves. During the ISIS trial, the whimsical figures were joined by heavily armed police and bomb-sniffing dogs. On the day of sentencing, I ended up waiting in line with Yusuf’s family as we went through security. They were preparing for the worst, they told me. His lawyers were too. Simply buying a ticket to Syria to join ISIS was considered “material support” for terrorism and could carry a 20-year sentence. After months of discussion with the FBI, Yusuf agreed to testify against his friends. The rumor around the courthouse was that because he’d been so helpful, he was likely to catch a break and get five years.

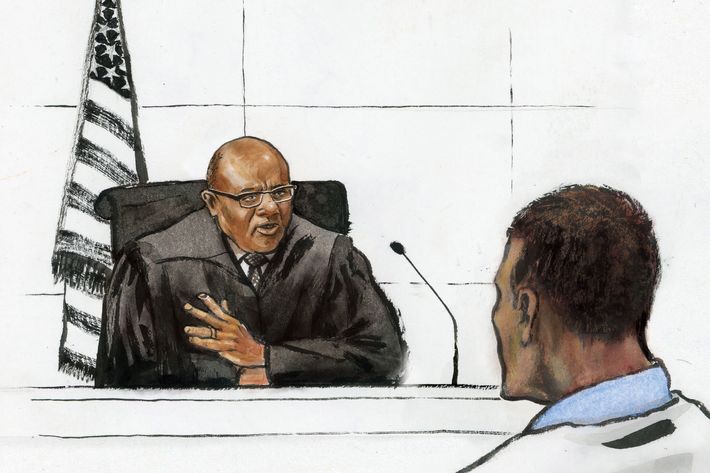

Davis had decided to announce the sentences for the whole group of ISIS recruits — those who’d pleaded out and those who’d gone to trial — in one go, over three consecutive days. Yusuf, the only one among them who’d been placed in jihadi rehab, was the first on the docket.

The proceedings started ominously. Davis cued up a series of violent ISIS videos and asked Yusuf if this was what he’d been watching in the months before he was stopped at the airport. The judge then asked about the counseling program: Did Yusuf understand that what he had done was wrong?

“Yes, sir,” Yusuf said quietly, his hands clasped respectfully behind his back.

Davis flipped through the papers on the bench, took a long look at Yusuf, and sighed. “I just don’t see how prison will help this boy.” Then he imposed a sentence no one expected: Yusuf would have to spend a year in a halfway house, followed by 20 years of supervised release. A literal gasp went up in the courtroom. The judge’s leniency largely ended with Yusuf. Omar got 35 years, and even the young men who’d pleaded guilty received lengthy sentences.

Yusuf’s year in the halfway house ended on November 9, when he was released to his parents. “When I think of what I want to do, it’s something that helps people,” he told me the last time I talked to him. “I want to go to school.” I asked if he’d ever thought about how different his life might have been if he hadn’t been assigned to study Syria in that high-school class.

“Yeah, why couldn’t I have gotten New Zealand or something, right?”

Dina Temple-Raston is the host and executive producer of “What Were You Thinking: Inside the Adolescent Brain,” a new series that debuts on Audible in January. The first episode about Abdullahi Yusuf is available at audible.com/adolescentbrain.

*This article appears in the November 27, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.