Assuming it never plunges the planet into a nuclear winter, Donald Trump’s incompetence will be one of his presidency’s saving graces. The demagogue-in-chief has exposed the fragility of America’s democratic institutions, and the openness of (many of) its people to authoritarian rule. But he’s proven far too lazy to exploit these liabilities. No dictator has ever executed a coup while setting aside four to eight hours a day for watching cable news on DVR, and virtually every weekend for a golf vacation. Beyond mitigating the tail risk of totalitarianism, Trump’s ineptitude has also impaired the GOP’s legislative agenda, and dampened his prospects of reelection.

And yet, even the president’s bitterest enemies have given him credit for efficacy on one front: bending the regulatory state to his donors’ whims.

By weaponizing the rarely used Congressional Review Act (CRA) — a law that empowers Congress to repeal any regulations enacted within the final 60 legislative days of its previous session — Trump nipped 15 Obama-era rules in the bud. Using this tool, the White House expanded the liberty of coal companies to dump mining waste in streams; allowed internet-service providers to track and sell consumers’ data without seeking their permission; banned states from setting up retirement savings plans for private-sector workers (a betrayal of federalism that serves no purpose beyond eliminating one of Wall Street’s potential competitors); freed employers from the responsibility of logging all workplace injuries; ended discrimination against serial labor-law violators in the bidding process for government contracts; and made it harder for consumers to sue banks that defraud them.

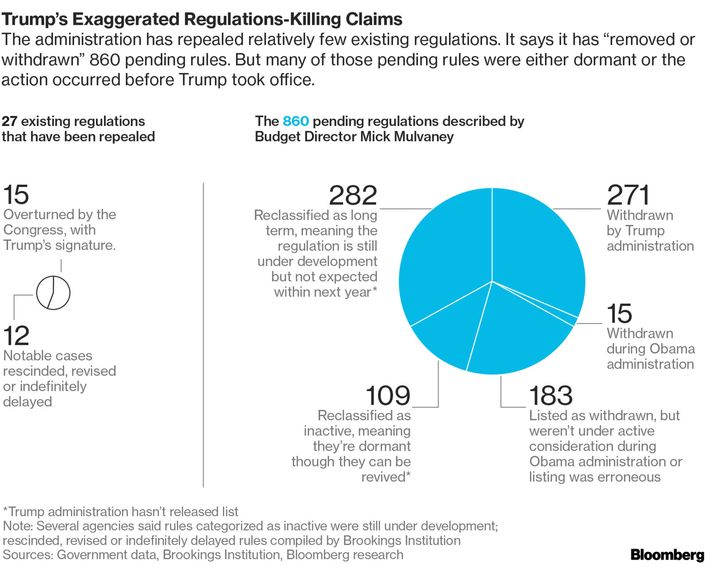

This blitzkrieg of repealed rules — combined with Trump’s decision to put foxes in charge of all of the federal government’s henhouses — projected an image of regulatory revolution. And the administration aimed to cement that impression last month, when it boasted that Trump had eliminated “nearly 1,000” regulations during his first year in office.

But that astronomical figure raised eyebrows. And in fact-checking the White House’s audacious claim, Bloomberg discovered that Trump has made far fewer lasting changes to the federal rulebook than he has claimed (or that many of his progressive foes had feared):

Of the 469 regulatory actions the Trump administration said it had “withdrawn” this year, 42 percent were as good as dead already. Some 180 of them weren’t listed on President Barack Obama’s final agenda of upcoming rules, meaning there were no immediate plans to impose them.

In many cases, there had been no activity on them in years, records show. Another 15 had been halted under Obama before Trump took office. At least three more were listed in error or were moot because the rulemaking was continuing.

For example, the Environmental Protection Agency abandoned its effort to regulate forest roads in July 2016—more than six months before the president took office—according to a notice in the Federal Register. Yet the withdrawal of that measure was counted as a Trump deregulatory action.

Also listed: an effort to create tougher regulations on mercury contamination that had seen no official activity since 2011.

Now, none of this means that Trump’s impact on America’s regulatory climate hasn’t been significant. His use of the CRA to wipe out the final regulations of the Obama era was unprecedented — before Trump the law had only been deployed to kill a duly enacted federal rule once. But outside of CRA-induced repeals (which primarily affected rules that hadn’t gone into force yet), the Trump administration’s efficacy at deregulation owes less to its competence at rewriting regulations than its willful incompetence at enforcing them.

Over the weekend, the New York Times documented the fruits of Scott Pruitt’s “soft on (corporate) crime” approach to leading the EPA:

The Times built a database of civil cases filed at the E.P.A. during the Trump, Obama and Bush administrations. During the first nine months under Mr. Pruitt’s leadership, the E.P.A. started about 1,900 cases, about one-third fewer than the number under President Barack Obama’s first E.P.A. director and about one-quarter fewer than under President George W. Bush’s over the same time period.

In addition, the agency sought civil penalties of about $50.4 million from polluters for cases initiated under Mr. Trump. Adjusted for inflation, that is about 39 percent of what the Obama administration sought and about 70 percent of what the Bush administration sought over the same time period.

The E.P.A., turning to one of its most powerful enforcement tools, also can force companies to retrofit their factories to cut pollution. Under Mr. Trump, those demands have dropped sharply. The agency has demanded about $1.2 billion worth of such fixes, known as injunctive relief, in cases initiated during the nine-month period, which, adjusted for inflation, is about 12 percent of what was sought under Mr. Obama and 48 percent under Mr. Bush.

Meanwhile, Mick Mulvaney has paralyzed the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau; the Commodity Futures Trading Commission has sought roughly 68 percent less in regulatory sanctions this year than did it one year ago; and the Labor Department has declined to enforce an Obama-era regulation limiting how much toxic beryllium companies can expose their workers to. Meanwhile, the Justice Department’s civil rights division has abandoned combating discriminatory police abuse against African-Americans — and concentrated on the (supposed) structural racism white people face in college admissions.

This litany could go on for pages. And in many ways, failing to enforce a federal rule can be as effective as repealing it. In the short term, the implications for citizens’ health, financial security, and workplace safety are profound. And to the extent that undermining an agency’s core mission chases civic-minded bureaucrats out of the federal government (more than 700 EPA employees have quit since Pruitt took the reins), Trump’s imprint on the administrative state could outlive his presidency.

All that said, at the end of the day, enforcement priorities are still one of the easiest things for a new administration to reverse. Where implementing his regulatory agenda has required procedural ruthlessness and a capacity to sow deliberate dysfunction, Trump has been immensely successful. But where it has required legal and political skill — which is to say, where it has involved making permanent changes to federal law — the president’s performance has been unexceptional.