Donald Trump and his congressional allies spent most of last year trying to push 22 million Americans off of health insurance. A new survey from Gallup and Sharecare suggests they came up about 19 million short.

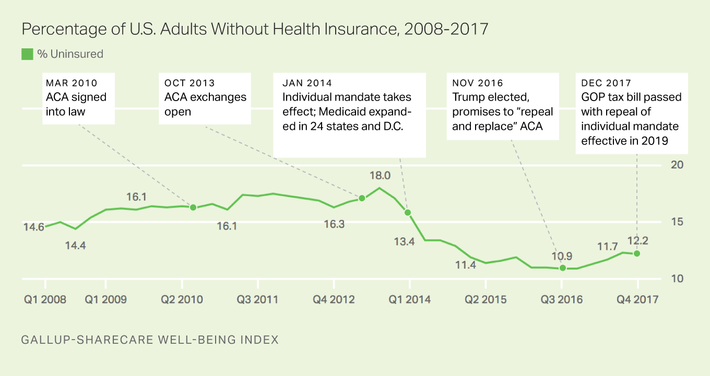

Although Trump & Co. failed to pass an Obamacare-repeal bill, their concerted efforts to undermine the law — on both the legislative and administrative levels — ultimately bore fruit. At the end of 2016, a record-low 10.9 percent of Americans lacked health insurance; by the end of last year, that percentage had risen to 12.2. That’s the first annual increase in the uninsured rate since the Affordable Care Act took effect, one that leaves 3.2 million previously insured Americans without coverage.

The decline in coverage was concentrated among Americans who had previously bought their own insurance (ostensibly, through Obamacare), as opposed to those who’d previously received insurance from their employer or Medicare or Medicaid. The drop-off was pronounced among young adults, blacks, Latinos, and low-income households — all demographic groups that the Obama administration had specifically targeted in its enrollment efforts.

Without a critical mass of young, healthy people participating in the Obamacare marketplaces — and thus, subsidizing the medical costs of the old and/or unhealthy — insurers must either jack up their premiums to maintain profitability, or exit the individual marketplace entirely. The ACA’s primary tool for nudging such “young immortals” into the marketplace was the individual mandate, which imposed a small tax penalty on Americans who chose to go uninsured. From the moment Trump took office, his administration sowed doubt about whether that mandate would be enforced, and its repeal was a core part of the various health-care bills that the congressional GOP tried to pass. These actions likely contributed to a 2 percent increase in the uninsured rate of 18 to 25-year-olds. Among black and Hispanic adults of all ages, the uninsured rate ticked up by 2.3 and 2.2 percent, respectively.

All this said, the Gallup-Sharecare survey’s findings should be taken with a grain of salt. The margin-of-error on the survey is 1 percent, and thus, it’s possible that the pollster’s findings exaggerate the increase in the uninsured rate. The latest National Health Interview Survey found the number of uninsured increased by only 200,000 over the first half of 2017.

Regardless, the White House’s most aggressive attempts to sabotage Obamacare came late in the year, and were concentrated on swelling the uninsured rate for 2018. Trump’s Health Department cut funding for the law’s outreach groups; slashed Obamacare’s advertising budget by 90 percent; spent a portion of the remaining ad budget on propaganda calling for the law’s repeal; cut the open-enrollment period by 45 days; announced that it would be taking Healthcare.gov (where people can enroll in Obamacare online) offline for nearly every Sunday during that time period, for “maintenance” purposes; and derided the law in official statements as “a bad deal” that “many won’t be convinced to sign up for.”

Despite these efforts, Obamacare enrollment for 2018 came in only marginally below the previous year’s tally. But in the absence of such concerted sabotage, enrollment would have almost certainly been far higher. And absent congressional action, the enrollment picture is likely to turn bleaker in the coming years. Republicans finally delivered a legislative blow to Obamacare with their tax bill, which abolished the individual mandate. This, combined with Trump’s decision to cancel the payment of cost-sharing reductions to insurers, has increased premiums on the individual market by double digits. Lower-income Obamacare enrollees will be insulated from this price spike, as they’re eligible for subsidies that rise in value with the cost of coverage. But for Americans who earn too much to qualify for subsidies — but still don’t receive insurance through their employers — Obamacare is a bad deal that just got dramatically worse.

Meanwhile, the administration’s new policy of encouraging states to impose work requirements for Medicaid is likely to increase the uninsured rate by depressing participation in that program.

Contrary to conservative talking points (but consistent with common sense), there is abundant evidence that giving low-income Americans health insurance leads to better health outcomes. A recent study of Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion in Arkansas and Kentucky found that low-income patients with chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, are far more likely to seek recommended care for their conditions now than they were previously.

The Trump administration does not bear full responsibility for Obamacare’s woes. The law’s mandate has always been too weak — and its subsidies, too meager and income-restricted — to realize its official goal of universal health care. Many Americans who don’t qualify for subsidies can’t afford the premiums on Obamacare plans — while others who do have access to subsidized insurance still can’t afford the deductibles. A Republican Party that put the interests of its constituents over partisan point-scoring and ideology would have helped the Obama administration amend the law to address its liabilities. But no such GOP exists.

Given the nature of the Democrats’ opposition, approaches to universal coverage that rely on complex, market-based mechanisms — that require regular maintenance and the good-faith cooperation of state governments — appear untenable. Medicare, by contrast, has emerged from Trump’s first year in office unscathed — and, according to reports, Republicans lack the stomach to take a run at it next year. On universal health care, the lesson of Trump’s first year is clear: It’s “big government” or bust.