It’s 10:45 p.m. Rio de Janeiro time. Glenn Greenwald and I are finishing dinner at a deserted bistro in Ipanema. The restaurant, which serves its sweating beer bottles in metal buckets and goes heavy on the protein, is almost aggressively unremarkable (English menus on the table, a bossa-nova version of “Hey Jude” on the stereo). Greenwald avoids both meat and alcohol but seems to enjoy dining here. “I really believe that if I still lived in New York, the vast majority of my friends would be New York and Washington media people and I would kind of be implicitly co-opted.” He eats a panko-crusted shrimp. “It just gives me this huge buffer. You’ve seen how I live, right? When I leave my computer, that world disappears.”

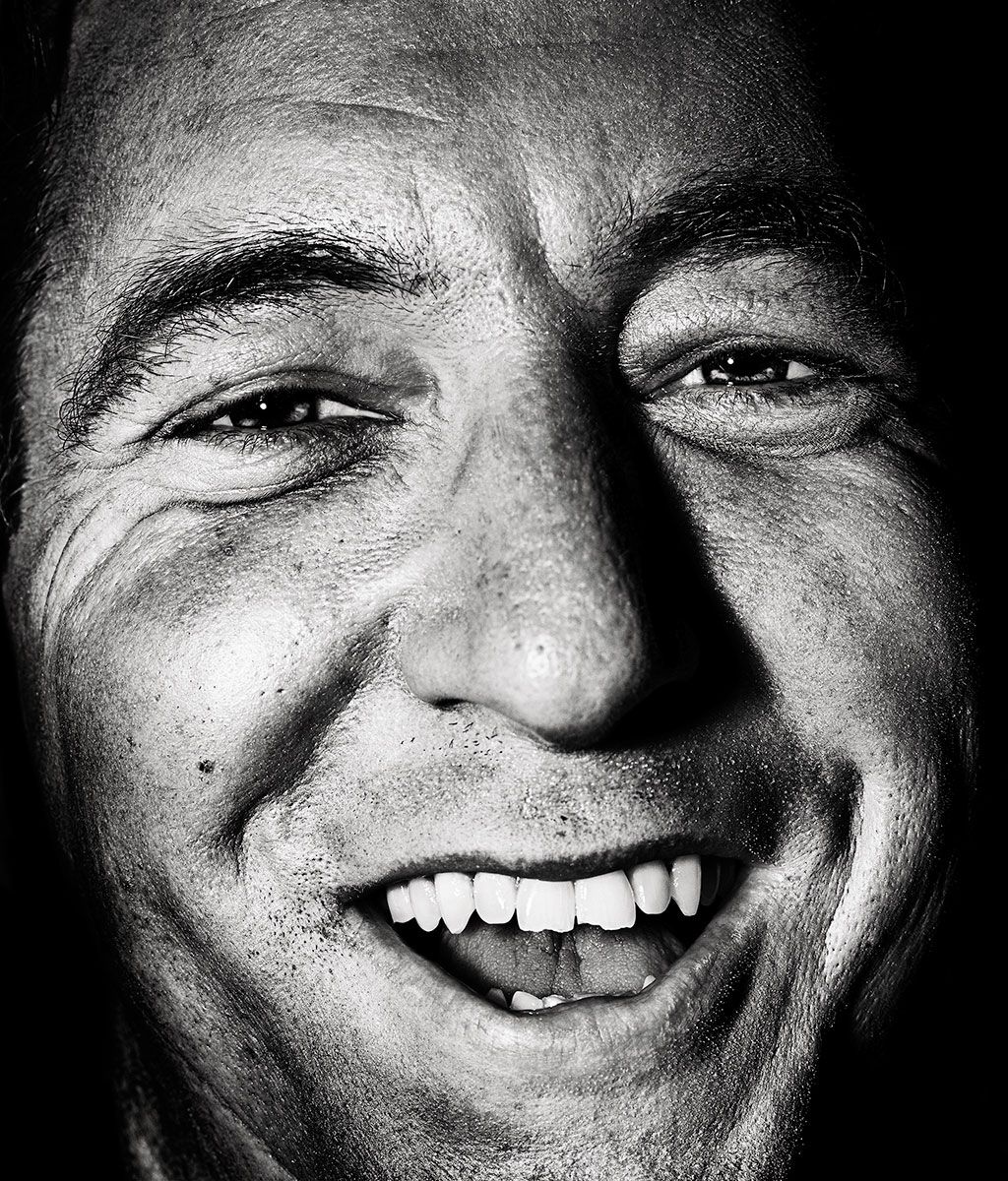

Greenwald, now 50, has seemed to live in his own bubble in Rio for years, since well before he published Edward Snowden’s leaks and broke the domestic-spying story in 2013 — landing himself a Pulitzer Prize, a book deal, and, in time, the backing of a billionaire (that’s Pierre Omidyar) to start a muckraking, shit-stirring media empire (that’s First Look Media, home to the Intercept, though its ambitions have been downgraded over time). But he seems even more on his own since the election, just as the agitated left has regained the momentum it lost in the Obama years.

The reason is Russia. For the better part of two years, Greenwald has resisted the nagging bipartisan suspicion that Trumpworld is in one way or another compromised by a meddling foreign power. If there’s a conspiracy, he suspects, it’s one against the president; where others see collusion, he sees “McCarthyism.” Greenwald is predisposed to righteous posturing and contrarian eye-poking — and reflexively more skeptical of the U.S. intelligence community than of those it tells us to see as “enemies.”

And even if claims about Russian meddling are corroborated by Robert Mueller’s investigation, Greenwald’s not sure it adds up to much — some hacked emails changing hands, none all that damaging in their content, maybe some malevolent Twitter bots. In his eyes, the Russia-Trump story is a shiny red herring — one that distracts from the failures, corruption, and malice of the very Establishment so invested in promoting it. And when in January, as “Journalism Twitter” was chastising the president for one outrage or another, Congress quietly passed a bipartisan bill to reauthorize sweeping NSA surveillance, you had to admit Greenwald might have been onto something.

“When Trump becomes the starting point and ending point for how we talk about American politics, [we] don’t end up talking about the fundamental ways the American political and economic and cultural system are completely fucked for huge numbers of Americans who voted for Trump for that reason,” he says. “We don’t talk about all the ways the Democratic Party is a complete fucking disaster and a corrupt, sleazy sewer, and not an adequate alternative to this far-right movement that’s taking over American politics.”

Greenwald’s been yelling about this, quite heatedly, since before the election. “In the Democratic Echo Chamber, Inconvenient Truths Are Recast As Putin Plots,” reads the headline of an Intercept piece published in October 2016. “The Increasingly Unhinged Russia Rhetoric Comes From a Long-Standing U.S. Playbook,” reads another, from February 2017. As Mueller’s investigation widened, no fallen domino — not the guilty plea of former Trump national-security adviser Michael Flynn, not the indictment of former campaign chairman Paul Manafort — chastened Greenwald. When it was recently reported that Steve Bannon had lobbed a “treason” charge in the direction of Donald Trump Jr. — precipitating his break with the president — Greenwald rolled his eyes. Bannon’s “motives are pure & pristine and he is simply trying to inform the public about the truth,” Greenwald tweeted sarcastically.

This is a year in which even the most anti-Establishment liberals have found themselves rooting for Mueller, a Republican who ran George W. Bush’s war-on-terror FBI. “It is not an insubstantial portion of Democratic online loyalists who believe that if you deviate from Democratic Party orthodoxy on the Trump-Russia question, you are a paid Kremlin agent,” Greenwald says. And many of those who don’t believe Greenwald works for Vladimir Putin tend to think he does his bidding for free. “I love him,” says former Gawker editor John Cook, who worked with Greenwald at the Intercept. “He’s dead, tragically wrong on this.”

Thanks to this never-ending hot take, Greenwald has been excommunicated from the liberal salons that celebrated him in the Snowden era; anybody who questions the Russia consensus, he says, “becomes a blasphemer. Becomes a heretic. I think that’s what they see me as.” Greenwald is no longer invited on MSNBC, and he’s portrayed in the Twitter fever swamp as a leading villain of the self-styled Resistance. “I used to be really good friends with Rachel Maddow,” he says. “And I’ve seen her devolution from this really interesting, really smart, independent thinker into this utterly scripted, intellectually dishonest, partisan hack.” His view of the liberal online media is equally charitable. “Think about one interesting, creative, like, intellectually novel thing that [Vox’s] Matt Yglesias or Ezra Klein have said in like ten years,” he says. “In general, they’re just churning out Democratic Party agitprop every single day of the most superficial type.” (Reached for comment, none of these people would respond to Greenwald.)

All this has led to one of the less-anticipated developments of the Donald Trump presidency: Glenn Greenwald, Fox News darling. For his sins, Greenwald has been embraced by opportunistic #MAGA partisans seeking to discredit the Trump-Russia story. When alt-right ringleader Mike Cernovich sat for a 60 Minutes interview last year, he praised only one journalist: Greenwald. “My opinion of Glenn ten or 15 years ago was entirely negative,” says Fox News’ Tucker Carlson, who now heralds him as one of the “clearest thinkers” in media. (A parallel phenomenon involves the rehabilitation by the Resistance of an armada of neoconservative zombies — David Frum, Max Boot, Robert Kagan, Bill Kristol — and the lionization, at least temporarily, of Trump-skeptical Republican politicians like John McCain, Jeff Flake, and Lindsey Graham.)

This, by the way, is the reason we’re eating dinner so late on a Tuesday: Greenwald has to be at a TV studio in a few minutes to be interviewed by Carlson. We leave the restaurant and head across the street to the garage where he parked his Mitsubishi Outlander. Unexpectedly, the gate to the entrance has been shut and the attendant is missing. Mild panic sets in. Greenwald begins rattling the gate. Even if we catch a cab to the studio, his TV clothes are in the car, and he is currently wearing shorts and an old polo shirt. “How,” he frets, “can I go on Fox News dressed like this?”

The parking attendant eventually shows up. There is no traffic; we book it to a high-rise studio with postcard views of Sugarloaf Mountain and Christ the Redeemer. Greenwald changes into a shirt and tie but keeps on his shorts and flip-flops. “I’ve never worn long pants when I’m appearing on TV,” he says with a grin. He is miked up and fitted with an earpiece, then forced to wait 20 minutes as his segment keeps getting bumped. The experience of actually listening to Carlson’s show seems to get to him.

“He’s on a huge anti-gun-control, anti-disarmament rant,” Greenwald tells me the first time I ask him what Carlson’s talking about. “Bullshit,” he says the second time I ask, rolling his eyes. By the time he goes live, it is 11:50 p.m., and Carlson asks just two questions.

“So I only had like three minutes,” he says, un-miking himself. “But it’s fine. It was worth it. It was cathartic.”

Greenwald’s home is located on a dead-end cobblestone street, under a thick canopy of trees, a few miles inland from Ipanema Beach. The grounds are large enough to comfortably accommodate Greenwald; his husband, David Miranda; their two recently adopted children; household staff; 24 formerly stray dogs; and some dog poop, which, when I visit the day before his appearance on Tucker Carlson Tonight, I step in.

Greenwald greets me in his cathedral-like living room dressed in his usual shorts and polo. When I joke that he lives in a gated community — a guard in a booth controls access to the street — he seems wounded and explains that he could afford the place only because the recent Brazilian recession had devastated Rio’s housing market. He plays coy when I ask him who owned the house previously. “I think it was some hedge-fund pig,” he says.

In person, Greenwald is funny and unguarded, which is the opposite of his online persona. Within minutes of my arrival, he launches into a story about a possible joint op-ed written with Katie Couric, before relaying a conversation he had with Ta-Nehisi Coates about how problematic it is to collaborate with people like Katie Couric. “It sounds like I’m obnoxiously name-dropping, and I’m not!” he says, catching himself. “But it was like, ‘How do you maintain your authenticity and the original kind of passion about the world that led you to be someone worth listening to, when now, suddenly, all these doors that had been previously closed are swinging open for you?’ ”

Greenwald grew up near Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He was closeted in high school and cultivated a rebel iconoclasm to cope. “One of the strategies you can develop is, I’m never going to be weak,” he says. “I’m always gonna be smarter and stronger and more aggressive.” Comparing himself to the titular character in the mockumentary American Vandal, he says he once prompted a schoolwide investigation by spray-painting the walls with “extremely offensive profanities about individual students and teachers.” “He was always warring with the administration, warring with teachers,” says his friend and former classmate Norman Fleisher. Instead of schoolwork, he devoted himself to the competitive-debate circuit and, in his senior year, to a failed bid for the Lauderdale Lakes City Council. He squeaked into George Washington University, where he majored in philosophy — Nietzsche — and again poured all his energy into debate. After that, law school at NYU, then a job at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, the most decorated and macho of the city’s white-shoe firms. In 1995, he left Wachtell to start his own litigation practice and carved a niche doing pro bono civil-liberties work, including defending neo-Nazi Matthew Hale.

Greenwald supported the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, but in 2005, when it became clear that the war on terror had produced a massive suspension of civil liberties — warrantless wiretapping, Guantánamo Bay — Greenwald abandoned his law practice and devoted himself to calling out the administration on his website, Unclaimed Territory. That year, he broke up with a longtime boyfriend, a psychotherapist. To unwind, he came to Rio alone, where he met the then-19-year-old Miranda. Their relationship did not, at the time, entitle Miranda to a visa — so Greenwald stayed in Brazil; Miranda is now the first openly gay city councilman in Rio’s history.

Early on, the mainstream press was docile in its coverage of the war on terror. Greenwald and his allies in the nascent left-wing blogosphere emerged to push back. “ ‘Barbarians at the gate’ was kind of the metaphor,” Greenwald says, and his prosecutorial hatchet jobs on the Bush White House became especially popular, despite (or perhaps because of) his exhausting, didactic prose. When he moved his blog to Salon in 2007, says his former colleague Alex Pareene, “editors would joke about the incredibly SEO-unfriendly headlines on his blog posts. Like, 3,000 words with the headline ‘And Another Thought.’ ” Twitter, when that was invented, proved irresistible to Greenwald. “I would wake up at like nine in the morning and see somebody saying something stupid on Twitter, and then it would be four in the afternoon, and I haven’t gotten out of bed.”

Once Obama was elected, the left blogosphere cleaved. “Some people, they revealed they’re mainstream, democratic liberals and defended a mainstream, democratic liberal administration,” says Pareene. “Others, they stuck to their line of opposition to the use of American power.” Greenwald was clearly in the latter camp, praising Ron Paul’s military isolationism and blasting the various “war criminals” who still ran D.C. Which meant that, by 2013, Greenwald, now writing for The Guardian, had spent a decade hurling invective at essentially everyone in Washington. To someone like Edward Snowden, those were unimpeachable bona fides. To others with more sympathy for the American Establishment, coordinating the publication of Snowden’s documents was something else. Greenwald hatred was intense not just in the intelligence community but also among would-be allies of transparency in the press; Andrew Ross Sorkin of the New York Times said he’d “almost arrest Glenn Greenwald.” Then–Meet the Press moderator David Gregory asked Greenwald if he should be charged for having “aided and abetted” Snowden. Greenwald was not wearing long pants during that interview, either.

Greenwald’s self-conception as an opposition figure, though, was getting more complicated. In 2014, Omidyar, the founder of eBay, poured $250 million into a news organization called First Look Media and handed Greenwald the keys. One of Greenwald’s collaborators on the Snowden story, the documentarian Laura Poitras, made a movie about the experience, Citizenfour, in which Greenwald was something of a second star. In 2015, it won the Oscar for Best Documentary, which Greenwald says he could not enjoy because host Neil Patrick Harris joked that “Snowden couldn’t be here for some treason.” At an after-party that night, a BuzzFeed reporter asked him about it. “I’m like, ‘I’m really trying hard not to say anything about it,’ ” Greenwald recalls. “And they’re like, ‘No, but you must have an opinion on it,’ and I was like, ‘Neil Patrick Harris is a fucking moron, and that joke was completely idiotic and offensive.’ ” (For the record, Snowden thought it was funny.)

Last September, Greenwald traveled to Santa Fe, New Mexico, to speak at an event held by the Lannan Foundation, an organization that offers prizes and speaking engagements to NPR-friendly types like Roxane Gay and Colson Whitehead. Wearing a light-gray suit and black Hugo Boss boots, Greenwald joked with the crowd for a few minutes before warning them that he wouldn’t be discussing the well-chronicled sins of the Trump administration. “I really don’t think you need me taking up your time talking about that,” he said. “And if you do for some reason want that, you can always just go home and turn on MSNBC.” Instead, Greenwald delivered an absorbing reading of the postelection landscape that fell somewhere between a troll job and a comprehensive articulation of his worldview.

The Trump election — because it upended countless political norms, because polls failed to predict it — was a psychologically destabilizing development. “When events happen that are so fucking out of the ordinary, people look for unifying events,” Greenwald tells me. “It becomes like a religion.” But Greenwald didn’t view the election as an aberration that needed to be explained. “Every time Trump says or does something that is xenophobic, or bigoted, or militaristic, or threatening, people always say, ‘This is not what America is about,’ ” he told the crowd in Sante Fe. “I always react to that by saying, ‘It’s not?’ ”

Rather than see Trump as a product of a rotten power structure, as Greenwald does, and the 2016 election as a wild reaction against that power structure, as Greenwald also does, it was easier for most American liberals to frame his victory as an accident. And rather than look within to eradicate the conditions that wrought Trump, it was more comforting to pin his rise on an external foe.

The Russian scandal proved ideal. “Across the political aisle, American elites are preoccupied with rejuvenating a Cold War in the name of believing that all of our problems are traceable to the Kremlin,” Greenwald argued. The notion that “Putin is not some fumbling dictator but some kind of an omnipotent mastermind,” he went on, “stems very much from this human desire to believe that when things go wrong, it can’t be our fault.”

Put another way: If you believe the 2016 election was a populist uprising against complacent elites, the Russia preoccupation can seem like an effort to ignore what Trump voters — and Sanders voters — were trying to say. Alternatively, if you believe Trump’s victory was a Russia-perpetrated fraud, normalcy is restored simply by removing him from office. Which, conveniently, is what many hope Mueller’s Russia probe will do.

The week I visit Greenwald in Rio, the news out of the D.C.-Moscow gyre is the indictment of three Trump-campaign aides: Rick Gates, George Papadopoulos, and Manafort. Sitting at Greenwald’s dining-room table, as a little dog named Kane molests a bigger dog named Enzo, I make the mistake of suggesting this is a “huge” development. Greenwald is ready for me before I finish my sentence.

“Have they been huge?” he pounces, answering his own question. “I mean, I guess they’ve been huge in the sense that Donald Trump’s former campaign manager was indicted on multiple felony charges, right? That’s inherently huge, but it’s not particularly huge for the Russia story, because all the charges leveled against Manafort were unrelated to questions of collusion with the Russians.” Fair enough, but Papadopoulos’s arrest was in fact related to the question of collusion. Greenwald waves this away. “They had all these kind of losers who weren’t even in the Trump campaign,” he says. “You know, these charlatans who were constantly puffing up their résumés, who come from the shittiest schools and have no significant experience.” He continues: “What happened this week, for me, is exactly what I’ve been expecting all along.”

True. Last March, Greenwald wrote an Intercept piece that forecast the “indictment of a low-level operative like Carter Page, or the prosecution of someone like Paul Manafort on matters unrelated to hacking.” His point then, as now, is that such developments are far removed from the original impetus of the investigation: whether Trump and Russia worked together to throw the election. “If you go back to what the Democrats were saying in 2016 and then into 2017, it wasn’t ‘Paul Manafort is laundering money and hiding taxes and failing to register forms about how he’s a foreign agent,’ ” Greenwald says. “Because that’s true of that entire scumbag lobbyist class in D.C.”

When it comes to what the investigation was designed to focus on, Greenwald says he’s still waiting for hard evidence that the Trump campaign aided Russian operatives in hacking the Clinton-campaign emails — or struck some other corrupt bargain. Absent that, he’s not impressed. “Some Russians wanted to help Trump win the election, and certain people connected to the Trump campaign were receptive to receiving that help. Who the fuck cares about that?”

Greenwald’s not wrong to criticize the zealotry of the Russia pile-on. The investigation’s boosters not only seem to ignore America’s own long history of election meddling (“Yanks to the Rescue: The Secret Story of How American Advisers Helped Yeltsin Win,” crowed a 1996 Time cover story) but also have elevated a bipartisan class of Russia conspiracists like Louise Mensch and Eric Garland to unfortunate prominence. Which is how, for instance, a deranged 127-tweet rant about “game theory” became cherished by liberals as a Russiagate decoder ring.

How did all this happen? In a recent issue of n+1, Cornell Law School professor Aziz Rana called 2016 the “last election of the Cold War.” What he meant was that for half a century, an unassailable Western consensus had prevailed that democracy and global capitalism were better than what the other team was offering. Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush, the presumptive 2016 favorites, reflected this consensus. Their dismal showings suggested the consensus had been busted, and among the signs that the political spectrum had broadened was the appearance of a new-seeming category of Russia-skeptic firebrands sometimes called the alt-left. Greenwald was one of the loudest voices, but there were others, many so divergent in their views of everything but Russia that it hardly made sense to group them together: the Trump-curious burn-it-all-down types; the “dirtbag left,” led by the irreverent politics podcast Chapo Trap House; anti-Zionist-anti-imperialists like Max Blumenthal; basically all of Russian television network RT’s on-air talent; retired NYU scholar and Nation eminence Stephen F. Cohen.

These critics note the irony that many who were critical of national-security abuses during the Bush and Obama years have now, in the name of defending the republic, put their faith in opaque intelligence agencies and retired generals. That uncomfortable alliance between liberals and the “deep state” is the Greenwald-Trumpworld relationship inverted; on Russia, the America Firsters in the White House share more with dovish lefties than with Washington’s centrist power elite. To borrow from the language of Brexit, the ideological split on the Russia question may be more “Leave” versus “Remain” than Republican versus Democrat. In other words, Establishment insiders versus skeptical outsiders.

“For me, the fundamental question is: How satisfied are you with the prevailing order, with the status quo?” By this, Greenwald does not mean life in the Trump era but the behavior of American elites over the past several generations. “How benevolent do you regard American power and American institutions?” The answer to that question says a lot about how you rate the Trump threat.

One afternoon, Greenwald and I drive to a sports club affiliated with Rio’s most popular soccer team, Flamengo. His mischievous and adorable children, Jonathas, 8, and João Vitor, 10, are scheduled for a tennis lesson at the club’s clay courts. It occurs to me that a tennis match with Greenwald would make an entertaining narrative stunt. Greenwald declines, telling me that he’s too good. “You’re going to feel bad because I’m going to destroy you, and you’re going to try and get vengeance on me through the profile.” That I’m cooking up a savage hit piece becomes a running joke throughout my visit — as does Greenwald’s inevitable reaction to my hit piece. “Unfortunately,” he imagines tweeting, “New York apparently has eliminated its entire editorial and fact-checking team as evidenced by this wretched article filled with lies. 1/29.”

In truth, a hatchet job probably wouldn’t bother Greenwald. He’s long positioned himself as a radical adversary of the courtier press corps; a hostile story would confirm his view. Indeed, the formidable team of investigative journalists that surrounds Greenwald at the Intercept reflects this bent. But the ambitions of the First Look Media empire have also been hobbled by Greenwald’s team-last M.O. In 2014, Greenwald co-wrote a lengthy piece documenting — and further contributing to — the company’s managerial dysfunction.

Greenwald’s half-a-million-dollar Intercept salary reflects his role as the founder and figurehead of the organization. But since the Snowden revelations, Greenwald hasn’t done much original reporting, and he has lately repositioned himself as a bomb-throwing media critic. This is in some ways a natural role for him, one that harks back to his early blogging days. “His general default position is that we shouldn’t believe anything the elite Establishment politicians are saying without fact-checking them,” says Jeremy Scahill, his Intercept co-founder. “We certainly shouldn’t believe the anonymous proclamations of CIA, NSA, FBI officials.”

Greenwald’s bunker mentality makes his Russia skepticism especially intuitive. “Every groove in his brain,” one Greenwald critic told me, burnishes his suspicion that the political and media Establishment has a vested interest in promoting the story. His Bush-era awakening created a built-in distrust of national-security apparatuses; his focus on U.S. power abuses tends to outweigh concerns about threats to the homeland; his isolationism makes him wary of belligerent rhetoric; his civil libertarianism demands that unpopular views not be censored.

In 2012, many liberals who now consider Kremlin-linked Facebook memes an act of war mocked Mitt Romney for calling Russia our “No. 1 geopolitical foe.” Greenwald, meanwhile, has been more consistent. “He’s always minimized whatever the threat vector that people like me were concerned about,” says Lawfare editor Ben Wittes, a longtime Greenwald opponent and unlikely celebrity of the Russiagate media sphere. “He’s doing the exact same thing now. Just that the threat vector we’re concerned about is the Russian state versus our leadership.” Wittes adds, tongue in cheek: “In Glenn’s defense, he has never purported to be a patriot.”

To listen to intelligence veterans, there is also a defensive aspect to Greenwald’s collusion skepticism. “You really cannot dismiss as part of his motivation the way in which this new story is undermining the very things that he made his reputation on,” says cybersecurity expert Stewart Baker, a former NSA general counsel. “Which is: embracing WikiLeaks and Snowden and a hostility to the idea that there are national-security threats the U.S. has to respond to.”

Journalistically, the problem with this dynamic is there’s virtually no revelation in the Russia story that could get Greenwald to change his mind. Which means that while Scahill and other Intercept colleagues tend to evaluate each new revelation at face value, Greenwald focuses disproportionately on debunked or overblown Russia stories. Ever the lawyer, he curates evidence that suits his argument. More than a year ago, the Washington Post published an erroneous story alleging that Russia had hacked into a U.S. electrical grid in Vermont. Greenwald continues to bring this up. To him, it’s not just a random piece of bad reporting but a crucial exhibit in a case he’s building.

Which makes his lack of interest in a report the Intercept itself produced all the more curious. In June, it published an explosive story that Russia had attempted to infiltrate voter-registration systems days before the election by sending phishing emails to more than 100 local election officials. The information came from a leaked NSA report; shortly before the Intercept published its story, a Georgia NSA employee named Reality Winner was arrested on espionage charges. Almost immediately, the Intercept was accused of exposing Winner with its own sloppy methods. But the scoop itself represented one of the first credible claims that, more than trying to influence American voters, Russia may have been directly targeting election technology. Greenwald distanced himself from the bungled leak at the time and now says he doesn’t buy the story outright. “I never liked the story. I thought it was bullshit and knew it was going to be huge in a way that was totally unjustified in what it actually revealed,” he says. “I think it tried to overstate the importance of what that document was.”

Greenwald’s selective outrage has become habitual. In November, The Atlantic published Twitter correspondence from 2016 in which a WikiLeaks representative gave Donald Trump Jr. campaign advice.

Greenwald pooh-poohed the coordination, implying that Julian Assange was just playing his usual 4-D chess. Barrett Brown — a pro-transparency autodidact who served more than four years in federal prison for spreading hacked data and won a National Magazine Award for Intercept essays he wrote while incarcerated — was livid. “He doesn’t seem to be engaging on the actual revelations that keep coming out on Russia and Trump’s people,” Brown says. “My best guess is he’s just ignoring these things in favor of the less difficult argument that some people who are backing the Trump-Russia narrative are full of shit.”

It probably doesn’t matter to Greenwald in the end how many new details emerge about Russia. The big truth — that American society is in dire need of reform and Russia is not to blame for that — can never be dislodged by the little truths. Still, in the weeks following my visit to Rio, Greenwald seemed to grow self-conscious of his alienated stance. On December 8, he emailed me that he’d been asked to appear on the Sean Hannity Show to talk about his criticism of a CNN story about emails between Trump’s team and WikiLeaks that he considered “the biggest fuck-up yet in the Trump/Russia story — totally humiliating.” A few hours later, he reconsidered. “Actually I’ve decided to take the opportunity to go on and just spend the whole time bashing the shit out of Fox and Hannity rather than doing what they want me to do: attacking CNN.” Later, he sent this: “Reading up now on all the Fox Fake News scandals of the year — what a fucking list.”

Ultimately, after being asked to appear on all three of Fox News’ prime-time programs, he went on Laura Ingraham’s show, where he fulfilled his promise to bash Fox News. The next morning, Greenwald tweeted a clip of the confrontation to his 940,000 followers, then immediately got into an argument with somebody called @hoboken1111.

*This article appears in the January 22, 2018, issue of New York Magazine.