California was once the land of Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and John Birch socialites; a state that revolted against taxes and immigrants before it was cool. Now, it’s a stronghold of the #Resistance, replete with sanctuary cities, legal reefer, and equal-pay laws.

Understandably, many of the region’s old-school reactionaries have started to feel like strangers in their own land. And so, these Golden State culture warriors have developed a plan to make California great again. As USA Today (oddly) reports:

The founders of New California took an early step toward statehood Monday with the reading of their own Declaration of Independence from California, a state they describe as “ungovernable.”

Their solution: Take over most of current-day California — including many rural counties — and leave the coastal urban areas to themselves.

“The current state of California has become governed by a tyranny,” the group, led in part by vice chairman Robert Paul Preston, declared in a document published online.

… “After years of over taxation, regulation, and mono-party politics the State of California and many of it’s 58 Counties have become ungovernable,” the would-be founders of New California said in a statement this week, citing a “decline in essential basic services” including education, law enforcement, infrastructure and health care.

There are a lot of reasons to snicker at New California’s would-be Founding Fathers. The idea that rural Californians would have better education, infrastructure, and health-care services if only they had lower tax rates, and no access to state revenues generated in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Sacramento, is delightfully delusional. And, as election analyst J. Miles Coleman points out, the conservative utopia of New California would almost certainly be dominated by liberal Democrats.

More fundamentally, this is what we in the business call an “Old Man Yells at Cloud” story. There is approximately zero interest, among Californian elected officials from either major party, in breaking their state in two.

But there should be.

New California is a worthwhile project launched for the unworthiest of reasons. Rural Californians will not get better public schools by locking themselves into a much poorer, slightly less blue state. But their state would get a significantly fairer amount of representation in the U.S. Senate.

The upper chamber has become one of the most genuinely tyrannical institutions of our government. At the republic’s founding, the most populous state in the union was home to 11 times more people than the smallest; today, that disparity is more than six times as large: California’s 39 million residents have as much say in the Senate as Wyoming’s 585,500.

At present, about half the country lives in 40 of the nation’s states, with the other half packed into just ten. This population discrepancy doesn’t just give voters in small states vastly disproportionate power in the Senate, but also in the Electoral College. And the disparity is likely to grow ever more severe in the coming decades, as more and more Americans migrate from the rural heartland to the high-density cities where economic growth is now concentrated.

The malapportionment of the Senate already has enormous influence on our politics. Small states leverage their disproportionate influence to secure themselves more federal aid per capita than large ones. More critically, while there are bastions of progressive overrepresentation (Delaware, Rhode Island, Vermont, Hawaii), America’s least populous states, in the aggregate, lean firmly right. And the combination of the Senate’s bias toward conservatism and its use of the filibuster has killed many pieces of popular, progressive legislation in recent years. To take just one example, if the Senate were a democratic institution, President Trump would not have the power to hold 700,000 Dreamers hostage right now — because the Dream Act of 2010 would be law.

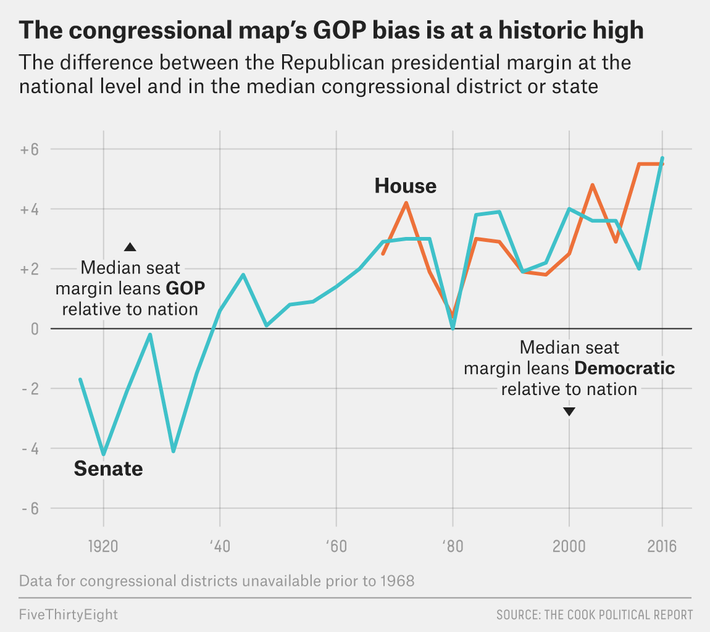

Today’s Senate map is more biased in the GOP’s favor than at any point in American history. And as the populations of small states in Middle America grow even smaller, older, and more racially unrepresentative of the broader country in the coming years, this bias could become a (more profound) threat to our government’s democratic legitimacy.

As outlandish as it may sound, breaking up large states into smaller ones may be the most plausible means of addressing this growing crisis of responsive government. Abolishing the Senate would require drafting a new Constitution (which wouldn’t be a bad idea, necessarily, but a pretty difficult one to pull off). By contrast, Congress can approve the addition of a new state by a simple majority vote in both chambers. Which is to say: The next time Democrats gain unified control of the government, they could use a razor-thin Senate majority to add new states that would likely expand that majority. The party’s first priority on that front should be D.C. statehood — and then, should the people of Puerto Rico petition Congress for admission to the Union, Puerto Rican statehood.

But addressing the underrepresentation of Californians would be worthwhile, too — if a less wacky and reactionary New Californian vanguard ever unites a critical mass of their compatriots behind the cry, “No taxation without slightly less absurd underrepresentation.”