The good folks beavering away at their long tables in the magisterial north Rose Main Reading Room on the third floor of the New York Public Library’s main building might be excused for feeling spied upon. “What is that thing?” they’ve been asking the guards over the past several months, pointing up at the eerie, tripod-mounted, radarlike dish mounted on the narrow balcony at the far end of the airy, vaultlike space.

Much of the time, the object is unmanned. But every once in a while, a lanky, long-haired young man will amble along the mezzanine balcony and squeeze himself into the narrow cockpit behind the dish, wedging his skull into a white helmet, and start taking measurements, or inventories, or calculations, or something. All very still, his arm jammed into the concave shell, scratching away infinitesimally, for hours on end (and indeed long after the place has otherwise closed down for the night). “What the hell is that guy doing?”

Well, in fact, he is taking a painstaking inventory of a sort: He is registering every single little thing in the visual surround. He is Trevor Oakes, one of the two “Perspective Twins,” who, along with his brother Ryan, has been engaged in a decades-long investigation into the nature of bifocal visual perception. The way that other identical twins might have evolved a hermetic secret language, the two of them (now in their mid-30s) have been exchanging ideas on what it is like to look and see with two eyes ever since they were barely toddlers, in Colorado and then West Virginia. They are the kind of of kids who (their parents once told me) could be found out in the woods, around age 10, seated on stumps 15 feet apart, shouting out surmises as to what the depth perception of a dragon with eyes that far apart might be like. And then in college, at Cooper Union during the early aughts, as a tangent to those sorts of speculations, they improvised a brand-new way of tracing camera-obscura-exact projections of the world, deploying no equipment whatsoever (no lenses, no mirrors, no projectors) except for their own two eyes (well, four eyes, but two at a time) and the visual cortex of their brains.

“You know how when you look out at some object in the distance,” they’ll expound, the one interrupting the other in well-practiced explanation, “say, that chandelier way over there, you can stretch out your arm and, closing one eye, block out the object with the pen in your hand. Switch eyes, and the pen will seem to have shifted over a few inches. But if you keep both eyes open, you will see a single chandelier and a double ghost of the pen.” Taking advantage of that effect, they apply one ghost pen to the page while the other traces the contours of the world beyond: a camera obscura using no other equipment than one’s own eyes.

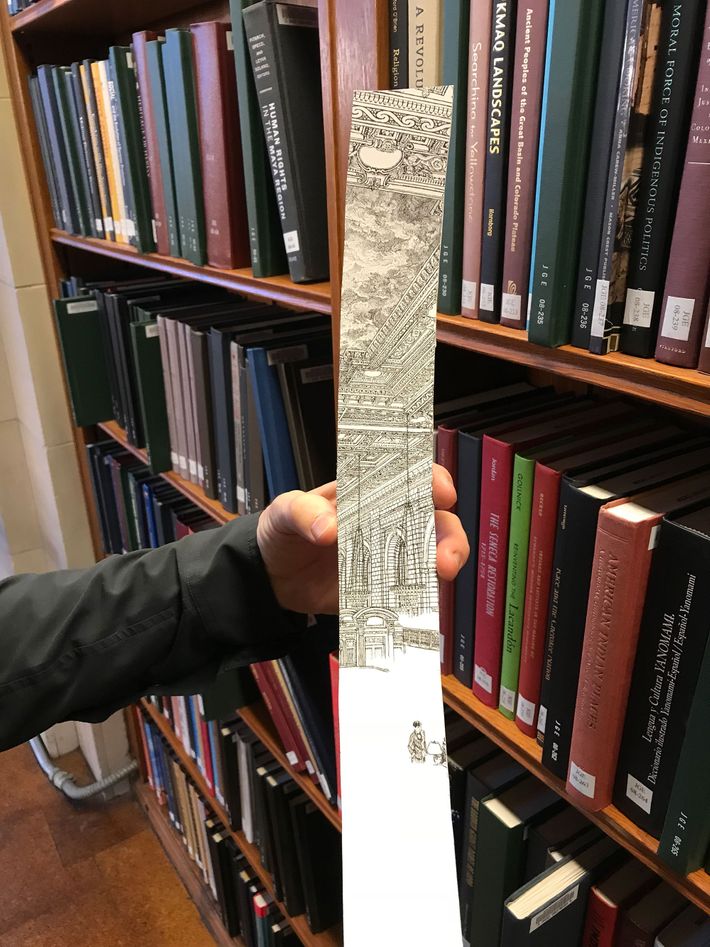

The effect works for a space on the page as wide as that between one’s two eyes; then, you have to tear that section away and start on the next. You have to keep your head and the page steady (hence the skullcap and the grid) and the method evinces huge Greenland-Mercator-like distortions at the top and the bottom unless you curve the grid, in keeping with the way we actually see (another discovery of theirs: not through a flat rectangular window but rather as if we are in the center of a 360-degree sphere, which we are).

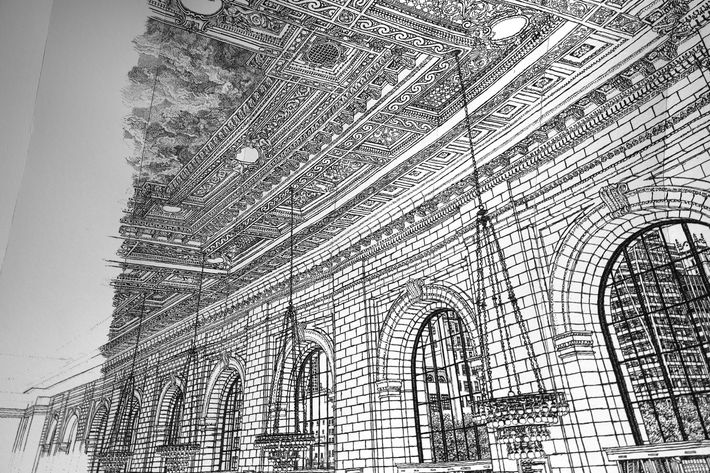

Over the past decades, the twins have rendered dozens of such concave drawings, one more complex than the next, though this one at the library is far and away their most complicated to date. (Trevor has become more adept at the actual tracing, while Ryan consults, constantly, on placement, theory, and so forth, and runs interference and the studio back home.) The process is so painstaking that they will likely be at this one for another several months. Consider the way that on the concave drawing, one row of shelves crammed with books is succeeded by another, equally crammed, and then above that the grid of the tall windows gets filled with the grid of the entire city beyond, all the layers distinct and the receding space crisply articulated. (“Every single brick, each book on each self,” avers Trevor. “It’s like I’m one of those people who somehow etch calligraphy onto a single grain of rice, only my canvas is an entire field of rice grains.”) In the drawing, the room is gradually filling with patrons at the long tables — almost exclusively friends of the twins, who drop by every once in a while to be immortalized. (The regular patrons don’t stick around long enough to be captured — they’d have to sit still for an hour or two.)

If you want to get a peek at the process in action, drop by this coming weekend’s Armory Show where samples of their work will be on display while atop a ten-foot platform, Trevor will be aiming his concave tripod grid at the hive of booths beyond, ghosting away.

*A version of this article appears in the February 19, 2018, issue of New York Magazine.